Could parenting apps help improve outcomes for children?

Analysing the market of early years apps for parents

Executive summary

Parents are now raising their children in an era of smartphone dominance. This presents new ways for parents to access support and advice on how to create a supportive and stimulating home learning environment for their children.

To learn more about the opportunities posed by parenting tech, we used data analytics to map the range of mobile apps for parents on the Google Play Store. We identified 303 apps designed for use by parents, from pre-conception through pregnancy and up to their child turning five. We identified six distinct groups of apps that:

- Track periods and fertility

- Track pregnancy

- Track babies’ rhythms

- Help babies to sleep

- Share baby photos

- Provide parental support

Of these groups, we are most interested in the parental support apps, which could have a significant impact on children’s outcomes by giving parents expert advice on how they can support their development. We look in detail at two case studies of apps in this category: Baby Buddy and EasyPeasy. These apps have both received UK government endorsement for their high-quality content and have also developed partnerships with central government and local public services in the UK to help drive parents’ uptake.

Our analysis of apps available on the Play Store finds that take-up of parenting apps seems to be slow overall: there was little to no growth in uptake between 2019 and 2021 based on user review data. This contrasts with the trends we are seeing in child-facing apps, where usage has spiked and remained high since the Covid-19 pandemic.

We conclude by identifying three opportunities for future innovation in the parent tech space, which Nesta is interested in exploring:

- Working with parents to co-design and experiment with ways to connect them with expert advice via digital channels

- Embedding digital tools in the delivery of local parent support services to help increase their reach

- Building evidence on the effectiveness of digital parental support tools for improving children’s social, emotional and cognitive outcomes.

Digital support for parents to create a home learning environment

In England, around 43% of children who claim free school meals are not reaching a good level of development in their reception year of primary school, compared with only 26% of their peers (DfE, 2019). Research suggests that the impacts of low family income on children’s early development may be both direct (for example, by reducing the resources available to parents to buy things their children need) and indirect, by putting additional stress on parents that can then impact negatively on their parenting capacity (Batcheler et. al., 2022).

Large, robust studies in England have shown that children’s home learning environment, including the quality of care they receive from caregivers and the types of resources available in their home, is associated with their development at age four (Melhuish & Gardiner, 2021). Children who have better cognitive outcomes at age four had a more stimulating home learning environment and a closer, warmer relationship with their parents (Melhuish & Gardiner, 2021). This is the case even when controlling for demographic factors such as family income.

At Nesta we have set out to find solutions that can help to close the school readiness gap for disadvantaged children. As part of this work, we are interested in the role that digital tools and resources could play in supporting parents to give their children a stimulating home learning environment. This report shares findings from new analysis that we carried out to take stock of the array of parenting apps that are already commercially available to parents. A companion piece discusses findings from our analysis of ‘toddler tech’ apps developed for young children.

Parenting in the smartphone era

Smartphone ownership is now fairly ubiquitous in the UK: more than 90% of adults aged between 25–54 now use their smartphone to go online (Ofcom, 2021). And internet usage is even more common: among parents of children aged 3–17, 99% had access to a broadband connection (Ofcom, 2022).

In this context, parents’ support networks and strategies for accessing parenting advice now draw on a combination of online and offline resources, including social media (DfE, 2019).

Uptake of pregnancy apps is higher among first-time mothers and those who have had a smartphone for longer (Rhodes et al., 2020). Mothers of young babies tend to use social media to access social support and information (Moon et al., 2019).

However, while this digitalisation of parenthood offers new routes to reach parents and support their children’s home learning, there are also challenges. App usage to support parenting may not yet be that widespread: less than a quarter of parents downloaded an educational app or game to support their child’s learning in 2018 (Zhang & Livingstone, 2019). Uptake of pregnancy apps has been shown to be lower among women with a lower income or whose first language is different from that of the app (Rhodes et al., 2020).

While we have reasonable data about uptake and usage, this is a fairly new field and there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of apps and other digital tools for improving children’s outcomes. We should also be aware of the risk of unintended consequences: in some circumstances, parents’ smartphone use could be a distraction from valuable interactions with their children (Batcheler et. al., 2022).

Our research: Mapping parenting tech

To learn more about the opportunities presented by parenting tech, what is available and how it is being used, we used data analytics to map the range of mobile apps for parents on the Google Play Store. Our focus on the Play Store was motivated by research from the US showing that lower-income smartphone users tend to have an Android phone, and Apple products are more associated with high income (Bertrand and Kamenica, 2018).

Landscape of apps designed for parents

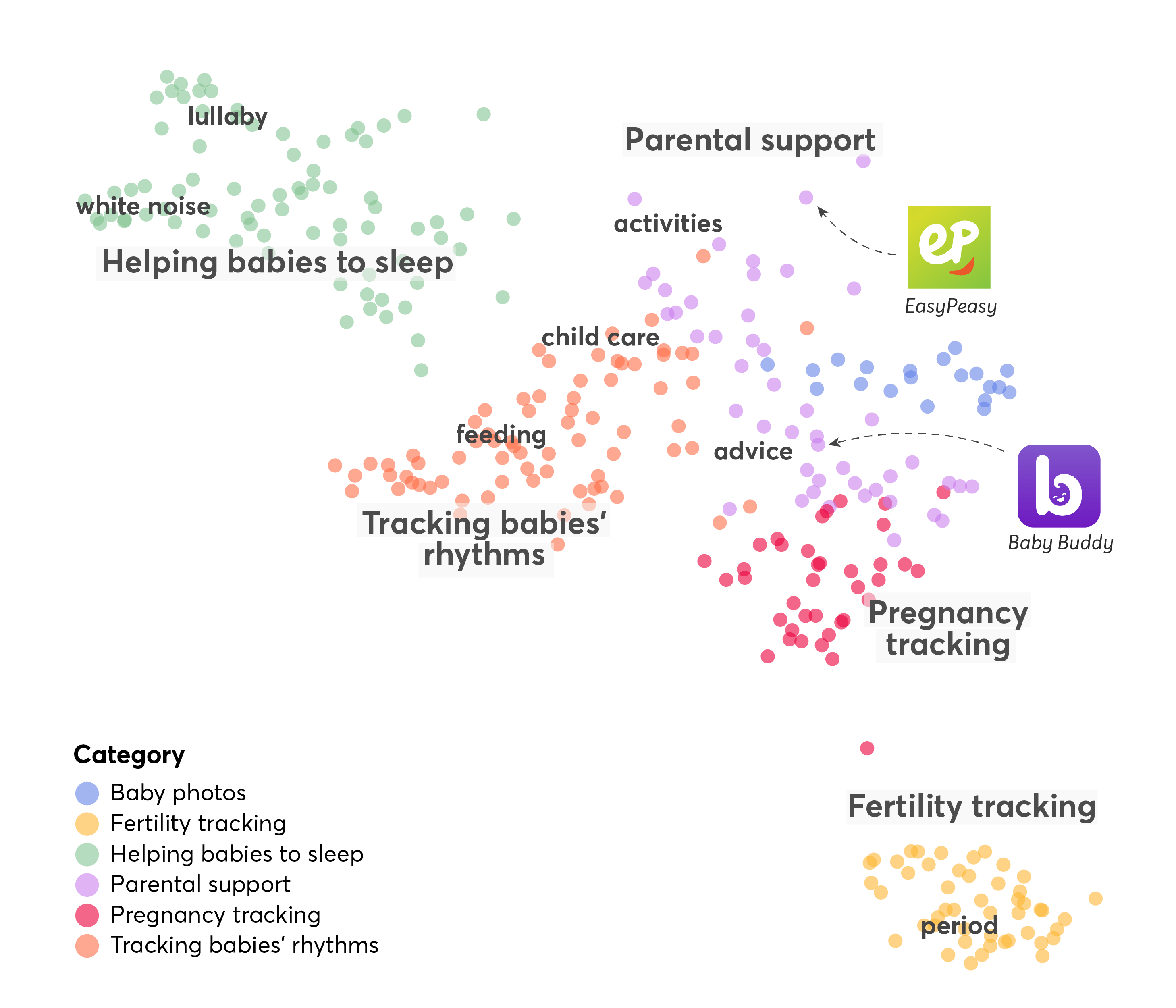

We identified 303 apps designed for use by parents, from pre-conception through pregnancy and up to their child turning five. We used an automated clustering process that identified six distinct groups of apps and provided a more granular assessment of the parent apps than the default ‘Parenting’ category on the Play Store.

Each app is visualised as a circle, with similar apps located closer together

An interactive version of the visualisation for desktop is also available.

An interactive version of the visualisation for desktop is also available.

The categories include apps that:

- Track periods and fertility

- Track pregnancy

- Help babies to sleep, including ones that play lullabies and sleep sounds, or track sleep schedules

- Track babies’ rhythms, for example by recording child developmental milestones or tracking sleeping and feeding

- Share baby photos, allowing parents to create albums and restrict who can see these albums

- Provide parental support, for example support for recovering after pregnancy, making it easier to find babysitting services, or advice on activities that facilitate their child’s early development and learning (for example, EasyPeasy and Baby Buddy, which we discuss in greater length below).

To illustrate examples of apps in each of our categories, the figure below shows the most popular parent apps in terms of installations. Each of these apps has been installed at least 500,000 times.

Apps with the largest number of installations

Hover the icons to see more information about each of the apps.

Emergence of parental support tech

While the number of apps in the parental support category appears relatively modest, this category has shown the strongest relative growth in terms of newly released apps in the previous five years. From our sample, we identified only two parental support apps released before 2015, whereas there were around nine new apps per year in the years between 2018 and 2020.

Number of Play Store apps by release year

Smoothed growth estimate between 2017 and 2021

By taking user reviews posted on the Play Store as a proxy measure of app usage, we find similar trends across the past five years. The ‘parental support’ apps appear to be just emerging with a relatively small number of average yearly reviews but high growth (170%).

Magnitude and growth of reviews between 2017 and 2021

Interestingly, during the Covid-19 pandemic between 2019 and 2021, we find indications of little-to-no growth in the uptake of apps targeted at parents, whereas there was a very high growth in apps targeted at children. This probably reflects parents’ increased need to keep their children occupied while childcare was interrupted during the pandemic.

As a more general underlying trend, businesses specialising in parenting tech appear to be attracting increasing amounts of venture capital investment. Among the companies raising investment, there are app developers such as Maple and Milo that make it easier to manage household tasks (for example, planning kids’ activities); services such as Tiney or Otter that connect parents to childminders (the latter of which raised £18 million last year); and apps like Nurturey that use speech recognition technology to develop a smart parenting assistant.

Taken together, these trends suggest that parental support apps and digital parent technologies are growing, but as we will discuss in the following section, their adoption at scale is yet to take off.

Lack of adoption of postpartum apps

In terms of the average number of installations, fertility and pregnancy apps appear much more popular compared to the other types of parent apps. We find that apps to track periods and fertility have the largest average number across our sample (five million installations), followed by pregnancy tracking apps (1.8 million).

In turn, postpartum apps for tracking babies’ rhythms, helping babies to sleep and parental support are markedly less popular, with the average number of installations ranging between 200,000 and 350,000. Therefore, there appears to be an overall drop in usage for postpartum apps compared to fertility and pregnancy apps.

Average number of installations (in thousands) from Play Store by app category

The average user scores for the parent app categories are quite high, with almost all categories having an average score of 4.3 or higher (out of five). However, only the ‘parental support’ apps stand out as the only category with an average score below four. To some extent, this echoes the app installation trends, but this difference seems to be too small to account for the large difference in popularity between prepartum and postpartum apps.

Average scores on Play Store by app category

Error bars indicate the typical range of variation of scores across apps (one standard deviation).

It could be that people have a positive experience of apps to support their pre-childbirth needs and are then disappointed with the subsequent offer or they find it harder to engage with apps once they become a parent. The small differences in terms of app scores suggests that postpartum apps may be of similar quality to the prepartum apps, but they are not yet reaching their users. This suggests that parents are using alternative sources of advice once their babies are born.

Case studies: supporting parents’ uptake of digital support

Among the apps for parents reviewed in this study, we are particularly interested in the ‘parental support’ apps. These have the potential to improve children’s outcomes by giving parents evidence-informed and actionable advice on how to support their children’s development. We’ve taken a closer look at two apps in this category, Baby Buddy and EasyPeasy, to learn more about how their developers are encouraging take-up among parents in the UK. We chose these two apps because they both have high-quality, evidence-informed content and have been endorsed by the UK Government.

Case study: Baby Buddy

The Baby Buddy app, developed by UK charity Best Beginnings, is designed to support parents from conception through their pregnancy and for one year after their child is born. It aims to tackle inequalities in child outcomes and improve parents’ and children’s health by giving parents reliable, expert information on topics such as:

- Healthy behaviours in pregnancy

- Infant feeding

- Mental health

- Supporting relationships.

The app has also been developed with a strong emphasis on accessibility and is free to users. The latest version of the app has been co-developed with input from a Parent Panel involving over 300 parents (a quarter of these are from Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic backgrounds). Its content is developed to be suitable for people with a reading age of nine and it includes over 350 short videos. The app also includes a specific user pathway for fathers.

Originally launched in 2014, the Baby Buddy app has now had registrations by more than 350,000 users. The second version of the app was launched in November 2021 with daily information and content specifically related to fathers.

Amongst these Baby Buddy users, data from 2021 show that:

- 88% were mothers, 6% fathers, 4% health professionals and 2% other categories

- 17.3% of mothers registered were from Black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups (compared with 19.9% nationally)

- Speakers of English as a second language are over-represented (13.8% of Baby Buddy’s users compared with 5.6% nationally)

- 8.14% of users have an annual income below £16,000 and 9.9% between £16,000-25,000.

User feedback on the app has been positive: user reviews collected within the Baby Buddy app find that 100% of users agree that the app is helping them feel more prepared for being a parent, 95% agree it is helping them to feel more confident caring for their baby and 91% agree it is helping them feel closer to their baby.

Parents’ uptake of the Baby Buddy app is currently promoted through partnerships with local NHS trusts and Clinical Commissioning Groups. The latest version of the app is currently being piloted across four sites in the UK: Surrey Heartlands ICS, Leeds, North East and South West London, using a collaborative approach to integrate Baby Buddy into maternity and early years care pathways. The top 15 local authorities using Baby Buddy over the first five months of 2022 are reaching over 30% of their birth cohort, with Leeds reaching 45% of their birth cohort and Havering reaching almost 61% of their birth cohort.

The app’s creators have also been working with local community leaders in Newham and Birmingham to encourage take-up of the app to support mental health and wellbeing in parent communities.

Case study: Easy Peasy

The EasyPeasy app is designed to provide parents with expert advice, tips and activity ideas for babies and children aged 0–5. It aims to support positive interactions between caregivers and children at home, to improve family dynamics and support early child development so that all children reach a good level of development by the age of five.

The app is free to download and uses an algorithm to personalise a content feed that is tailored to their child’s age and their interest in specific topics. The tailoring of content improves over time as the app learns from users’ data and interactions. The app also provides a community of early years experts and other parents who can create and share content through the app. This enables parents to connect with each other through the app, supporting peer-to-peer relationships.

The Early Intervention Foundation has rated the EasyPeasy app '2+' in its guidebook, meaning there is preliminary evidence of improving a child outcome. It states the app achieves outcomes in "children's mental health and wellbeing and children's cognitive self-regulation”. The EIF has also indicated that the programme has a low cost to set up and deliver.

There have been 172,216 registrations to date across EasyPeasy’s web app and native apps. EasyPeasy’s user base has an over-representation of disadvantaged families (49% of EasyPeasy users live in the 40% most deprived areas in the UK).

Parents’ user reviews of EasyPeasy in the Google Play store give the app an average rating of 4.5 stars out of 5. This is considerably higher than the average rating of apps we identified in the parental support category (3.9). A recent parent impact survey carried out by EasyPeasy found that:

- 93% of parents agree that as a result of using EasyPeasy, they know more about what they can do to help their child develop their personal, social and emotional skills

- 89% of parents agree that as a result of using EasyPeasy, they know more about what they can do to help their child develop their speech, language, and communication skills

- 95% of parents report that since using the app, they feel they can make an important difference to their child.

EasyPeasy offers licence agreements for local service providers, which enables them to distribute the app to local parents via a range of in-person and digital channels. This partnership model also gives local authorities access to a reporting dashboard, which they can use to monitor parents’ take-up and key data on how parents are engaging on the app. EasyPeasy’s Community Team offers paid-for packages of support for local service providers to help them drive local engagement. They also recently launched an EasyPeasy Pods initiative, which aims to encourage parents to meet in person and provide each other with peer support.

The EasyPeasy app has also been distributed to tens of thousands of disadvantaged families through a partnership with the Department for Education and the charity ICAN, as part of a national strategy to narrow the gap in school readiness.

As these case studies suggest, word-of-mouth recommendations and promotion via app stores are probably not sufficient to encourage wide scale take-up of parenting apps in the UK. The developers of Baby Buddy and EasyPeasy have both pursued partnerships with local public services in the UK to help promote uptake and regular usage by parents. Baby Buddy has been endorsed by the NHS and EasyPeasy has received endorsement from the Department for Education and NHS Scotland. This endorsement from trusted institutions as well as proactive engagement strategies may be particularly important to attract parents with lower incomes and those who are speaking English as an additional language (Rhodes et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Our analysis of parenting apps available on the Play Store shows that the number of commercially available parental support apps is increasing, with a few new apps released each year. However, parents’ take-up of these apps seems to be slow: if we use user reviews as a proxy, there was little-to-no growth in uptake between 2019 and 2021. This contrasts with the trends we are seeing in child-facing apps, where growth over the last few years has been strong.

Parenting support apps have the potential to help narrow the school readiness gap by bringing evidence-based advice and support to parents at low cost. However, it seems likely that this type of digital channel may be under-used in the UK. At Nesta we would like to learn more about how parents like to access support and the benefits and disadvantages of different channels including face-to-face support from professionals or peers and digital support via apps, social media or text message (including instant messaging apps such as WhatsApp).

As we can see from the Baby Buddy and EasyPeasy case studies above, there is an opportunity for local public services to help with signposting parents to access high quality digital forms of support. To ensure that uptake is sustained over time, initial work to promote digital resources may need to be combined with some form of ongoing engagement. Depending on what works best for parents, this might involve ongoing prompts and reminders from professionals (eg, health visitors), peer groups or digital channels (eg, text messages).

Some of the future priorities for innovation in this space that Nesta will be interested in exploring include:

- Working with parents to co-design and experiment with digital approaches to connect them with evidence-based advice on parenting. This might include a range of digital channels (eg, social media, digital messaging services, apps) and learning about what works best to engage different groups of parents

- Embedding digital tools in the delivery of local parent support services (eg, Best Start for Life and family hubs) and developing new hybrid support models to increase the reach of local services. These might involve a combination of professional support and/or peer support, plus digital tools to support access to expert advice and social connection with other parents

- Building evidence on the effectiveness of digital parental support tools for improving children’s social, emotional and cognitive outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Nazli Durusut, Rachel Parker and Jack Rasala for their help in reviewing the data-driven categorisation of toddler and parent apps.

We also extend our gratitude to Jen Lexmond from EasyPeasy and Nilushka Perera from Baby Buddy for providing us with information for the case studies of their apps.

We thank Eva Bee for the illustration, Cara Sanquest for giving advice on the communications strategy, Siobhan Chan for editing and designing this article, as well as Celia Hannon and Raj Chande for providing insightful comments throughout the project.

Carrying out the data analysis for this project would not have been possible without the availability of high-quality, open-source code libraries of the Python scientific computing ecosystem. In particular, we express our utmost gratitude to all the maintainers, contributors and supporters of the Google-Play-Scraper package.

For information on how we conducted our analysis, see the methodology section of our accompanying article on toddler apps. The case studies of Baby Buddy and EasyPeasy were put together by Nesta with information provided by the app developers.

References

- Batcheler, R., Ireland, E., Oppenheim, C., Rehill, J. (2022) Time for parents: The changing face of early childhood in the UK. London: Nuffield Foundation.

- Bertrand, M., & Kamenica, E. (2018). Coming apart? Cultural distances in the United States over time (No. w24771). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- DfE (2019) ‘Early years foundation stage profile results: 2018 to 2019’

- DfE (2019) Childcare and early years survey of parents in England, 2019

- Zhang, D. & Livingstone, S. (2019) Inequalities in how parents support their children’s development with digital technologies Parenting for a Digital Future: Survey Report 4. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Melhuish & Gardiner (2021) ‘Study of Early Education and Development (SEED): Impact Study on Early Education Use and Child Outcomes up to age four years’. University of Oxford.

- Moon, R. Y., Mathews, A., Oden, R., & Carlin, R. (2019). Mothers’ perceptions of the internet and social media as sources of parenting and health information: qualitative study. Journal of medical Internet research, 21(7), e14289.

- Ofcom (2021) Online Nation. 2021 Report.

- Ofcom (2022) Children and parents: media use and attitudes report 2022.

- Rhodes, A., Kheireddine, S., & Smith, A. D. (2020). Experiences, attitudes, and needs of users of a pregnancy and parenting app (Baby Buddy) during the COVID-19 pandemic: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(12), e23157.