Could toddler tech help to get more children school ready?

Analysing the market for children’s apps

Executive summary

In the UK, children from low-income backgrounds are less likely to be ‘school ready,’ with lower average scores for their development in language skills, maths and literacy when they start formal education. Nesta has set out on a 10-year mission to close this school readiness gap.

What role could digital technologies play in achieving this? To find out, we investigated trends in parents’ and children’s tech use in the early years. Children under the age of five use screens for around three hours a day on average (Kidscreen, 2021) and usage is higher among children from low-income backgrounds (DfE, 2019, Hendry et al., 2022), so we wanted to explore if this presents a potential opportunity to use digital technology to support early childhood development.

We analysed the Google Play Store to learn more about the market of apps aimed at parents and children in the early years. Of the 896 apps designed for children aged 0–5 that we found on the UK Play Store, some explicitly offer learning content while more than a quarter (249) offer general play with no explicit educational benefit advertised. Our analysis also showed that the toddler apps market is growing fast, with around 100 new apps released every year since 2016. Analysis of app reviews (as a proxy for app usage) indicates that usage of toddler apps increased substantially during the Covid-19 pandemic and has remained high.

Taking into account this growing trend of toddler tech, this report makes the case that the UK early years sector should consider the potential role of children’s screen time in helping to narrow the school readiness gap. We identify four key opportunities:

- Improving the quality of toddler tech so that it has greater benefit for children’s social, emotional and cognitive development

- Helping parents to navigate a crowded market so that it is easier to identify apps worth their children’s time

- Making high-quality content freely available to low-income families

- Developing the evidence base for how toddler tech can be used most effectively in the home environment to boost children’s outcomes.

Closing the school readiness gap

In England, around 43% of children who claim free school meals are not reaching a good level of development in their reception year of primary school, compared with only 26% of their peers (DfE, 2019). By the time they reach the age of five, children from low-income backgrounds are less likely to have reached expected levels of development in their language and communication skills, their literacy and their numeracy.

At Nesta we have set out to find solutions that can help to close this school readiness gap. In this report we explore the role that toddler tech might play in widening or narrowing the impact of social disadvantage on children’s outcomes.

The current state of (digital) play

During the Covid-19 pandemic, many parents relied on screens to keep their children occupied while schools and nurseries were closed (Guardian, 2021). Children under the age of five now watch an average of three hours of video content every day; an increase of nearly half an hour from 2019 (Kidscreen, 2021).

Technology use among UK pre-schoolers is now widespread (Ofcom, 2022). Among three- and four-year-olds:

- 78% use a tablet to go online

- 17% have their own mobile phone

- 89% use video sharing platforms like YouTube

- 21% use social media

- 18% play games online.

Parents give children aged 0–4 digital devices for a variety of reasons; to support their child’s learning (67%), to encourage play or creativity (49%), or to keep their child quiet (45%) (DfE, 2019). This research also found that young children in lower income households used technology more frequently. Nearly a third (32%) of children in households earning under £10,000 were using a digital device on a daily basis, compared with 13% of children in households earning £45,000 or more (DfE, 2019). This reflects a growing body of evidence showing that babies and toddlers from lower income backgrounds tend to have higher screen use (Hendry et al., 2022).

Risks and benefits of screen time

Should we be concerned about the rise of toddler tech? Not necessarily. Research indicates that viewing high quality educational programmes can benefit children’s cognitive development, including literacy, numeracy (Mares & Pan, 2013) and language development (Linebarger & Walker, 2005). A recent meta-analysis of 36 intervention studies found that educational apps have a positive effect on children's literacy and numeracy outcomes that is comparable to the effects of tutoring (Kim et al., 2021).

Screen time is more likely to be beneficial if:

- The child is aged two or older (American Academy of Paediatrics)

- Exposure is limited to short bursts eg, less than an hour per day (Ponti et al., 2017)

- Caregivers co-view with their children to help them interpret and discuss what they're viewing (Madigan et al, 2020)

- Children are watching high quality content that is age appropriate (Linebarger et al., 2017).

The Department for Education’s guidance for parents on early learning apps has also suggested that apps are more likely to be beneficial if they help children to learn something new; they encourage play and creativity; or they encourage interactions with others (DfE, 2019). Research also suggests that children aged 4 and older are more likely to benefit from educational apps, compared with younger children (Herodotou, 2018; Outhwaite et al., 2022).

However, screen time may pose a risk to young children’s development if it is in excessive quantities (Lin et al., 2015), it is not appropriate for their age group (Barr et al., 2010), they are not spending enough time interacting with caregivers (Meyer et al., 2021), they are not getting enough physical activity (Wen et al., 2014) or they’re using screens too close to bedtime (Garrison & Christakis, 2012).

So what digital tools are young children using? To learn more about current trends in toddler tech, we used data analytics to map the range of digital tools available to families with young children. Our analysis focused on mobile apps on the Google Play Store that were either targeted at parents, or at children aged 0–5. Our focus on the Play Store was motivated by research from the US showing that lower-income smartphone users tend to have an Android phone, and Apple products are more associated with high income (Bertrand and Kamenica, 2018).

A diverse market of mobile apps for toddlers and parents

Our first observation was the striking number of mobile apps. In the journey from preconception to preschool, parents and their children can choose between at least 1,200 different apps on the Play Store.

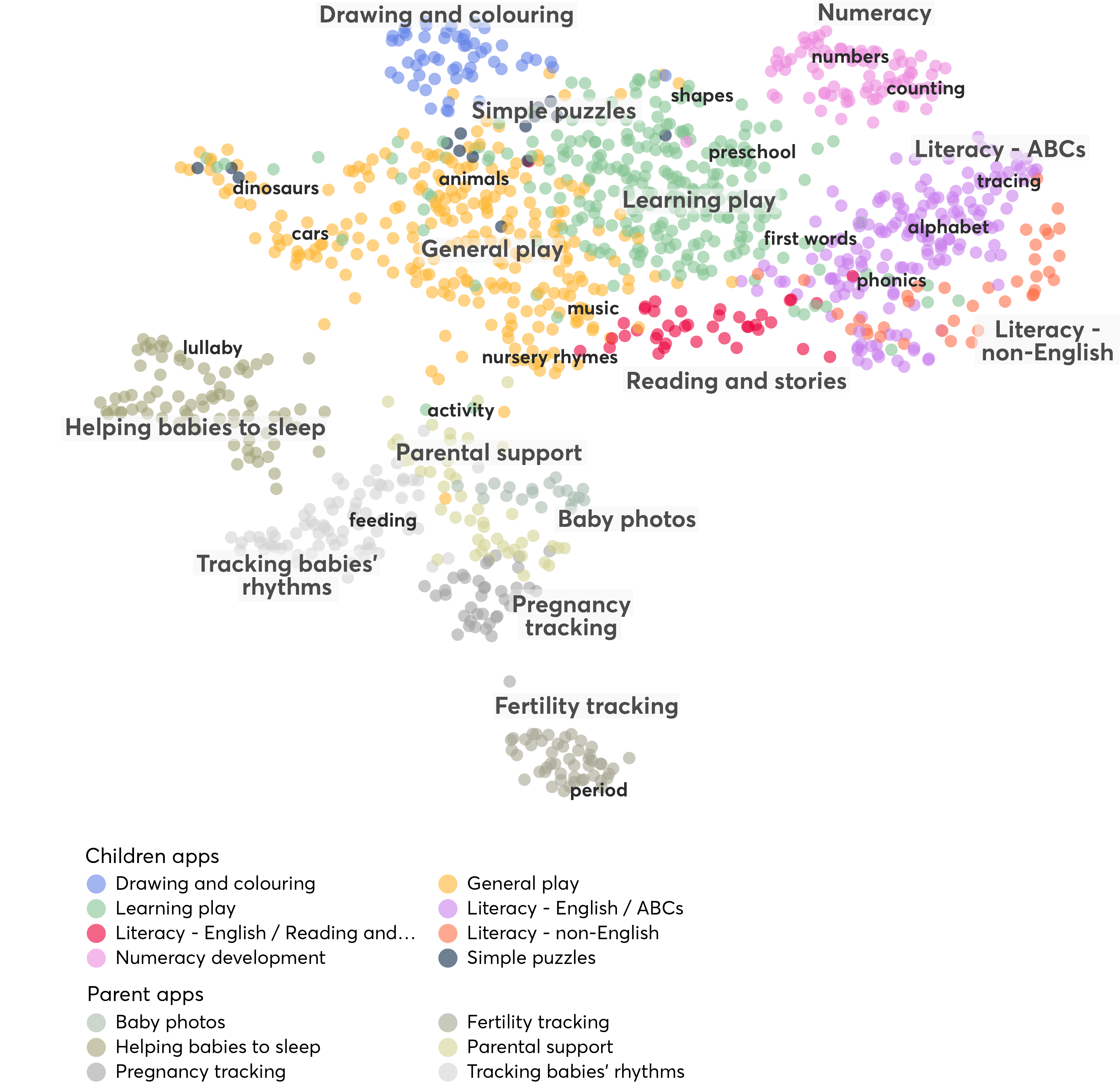

To characterise this landscape of apps, we used an automated clustering approach to group together similar apps based on their text descriptions. This yielded 14 categories which are more detailed than the default categories on the Play Store. The landscape of different types of apps is visualised in the graphic below.

Each app is visualised as a circle, with similar apps located closer together.

An interactive version of the visualisation for desktop is also available.

We found nearly three times as many apps aimed at children as we did for parents (896 and 303 apps, respectively). The children’s apps support entertainment, learning and playing, while the parents’ apps provide advice, allow parents to track babies’ activities and developmental milestones, and help put babies to sleep.

The number of new app releases for children has tended to grow faster compared to parenting apps. We find that about 100 new children’s apps have been released every year since 2016. This could be the case because more developers create apps for toddlers and each developer tends to produce a larger number of different apps, whereas those creating apps for parents are more likely to have a single offer.

Number of Play Store apps by release year

In the remainder of this article, we will characterise the apps aimed at children. A companion article looks more closely at the apps directly supporting parents.

Most toddler apps are for play, but some help with learning

The majority of the 896 apps aimed at children are oriented around games. There are two broad groups of such play-oriented apps: those that are “just” for play (and are, perhaps, more geared towards distracting children) and those that claim to include some aspect of learning. The apps for general play without an explicitly described objective to support child’s learning make up over a quarter of all apps (249).

A third of the children’s apps are intended to explicitly support children’s literacy and numeracy. Apps supporting early learning of phonics and letters are most numerous (more than 160 apps), followed by apps to develop numeracy (around 80 apps) and more general apps for reading stories (around 40 apps).

The figure below shows the most popular apps in terms of installations. Each of these apps has been installed at least one million times.

Apps with the largest number of installations

Hover the icons to see more information about each of the apps.

Among the educational apps is buddy.ai which uses voice technology to help children learn English. It’s part of a broader, rising trend of applying machine learning algorithms to recognise speech and support learning. Other emerging apps like Ello and bookbot act as reading coaches that listen to a child reading a story and can help them pronounce difficult words. While child speech recognition has been historically challenging to program, there are claims that it is now reaching a satisfactory level of accuracy, and companies specialising in this technology are attracting venture capital investment.

Parents may struggle to access high-quality apps

We know that parents mainly find apps for their children by searching an app store or by word-of-mouth (DfE, 2019). Given the crowded marketplace, it is likely that parents are finding it hard to navigate towards the apps that are most likely to benefit their children’s development.

A recent analysis of commercially available apps for young children found that the majority (58%) had low educational value. Apps that were free to download ranked among the lowest (Meyer et al., 2021). This is concerning, as free apps are (unsurprisingly) popular with parents: a survey by the Department for Education found that 78% of parents whose children used apps had never spent money on one (DfE, 2019). Children in lower-income families are also less likely to have access to paid-for apps (Marsh et al., 2015).

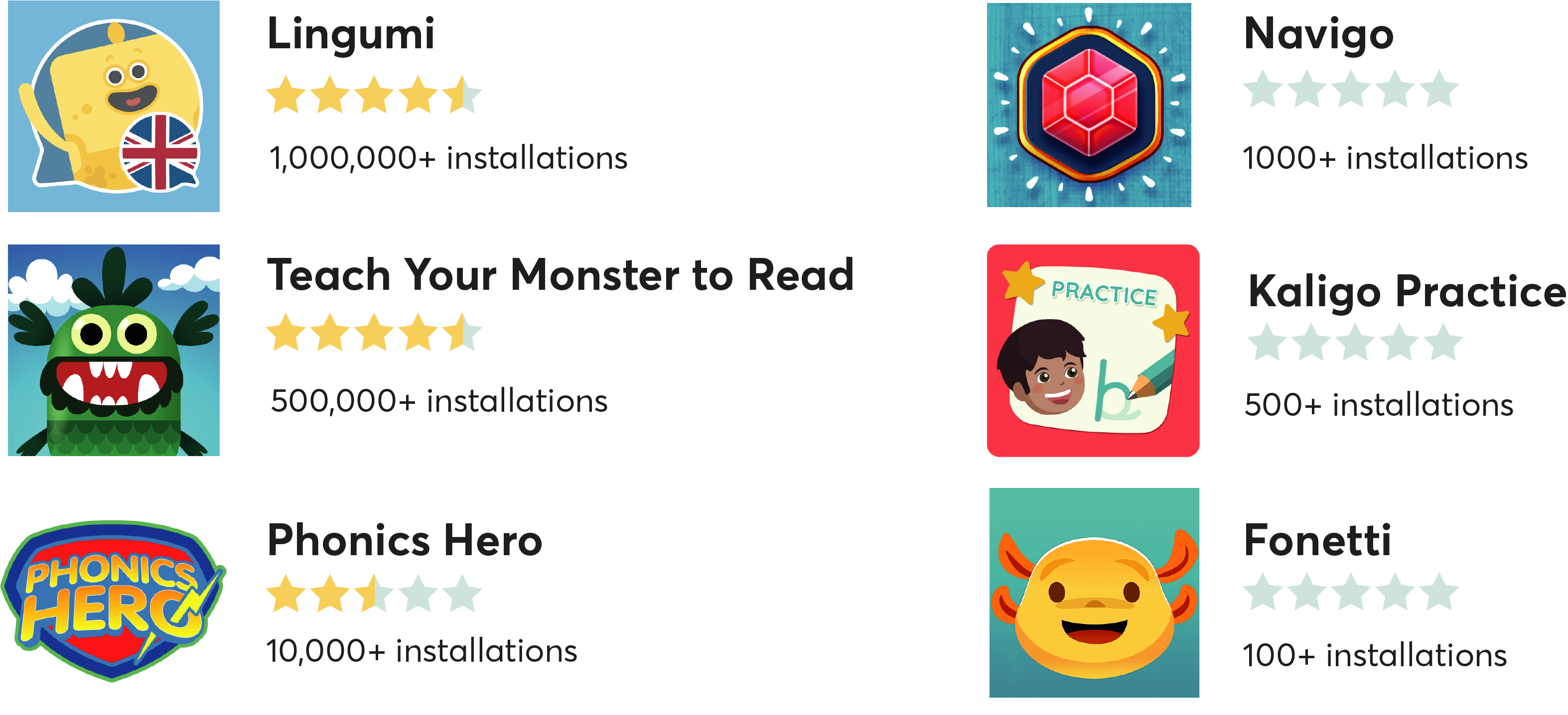

To help parents choose higher quality apps, the DfE has issued guidance to parents around what makes a good early years app. Based on this guidance, DfE endorsed six apps in 2020 as particularly suitable for creating a positive home learning environment. However, out of these DfE-endorsed apps, only two have more than 500,000 installations and are rated four stars or more (out of five). The third most popular DfE-endorsed app has 10,000 installations but a relatively low score of 2.6, while the three remaining apps have 1,000 installations or fewer and not enough ratings for the Play Store to report a score.

Average score and installation estimates from Play Store

Although these apps may be available in channels other than the Play Store, it seems that they are yet to hit the same scale as others in the market – for example, there are at least 360 other apps with over a million installations.

This suggests that issuing official guidance is not sufficient; we need more effective ways to direct parents towards the higher quality apps that are more likely to benefit their children’s development.

Parents are frustrated by ads and in-app purchases

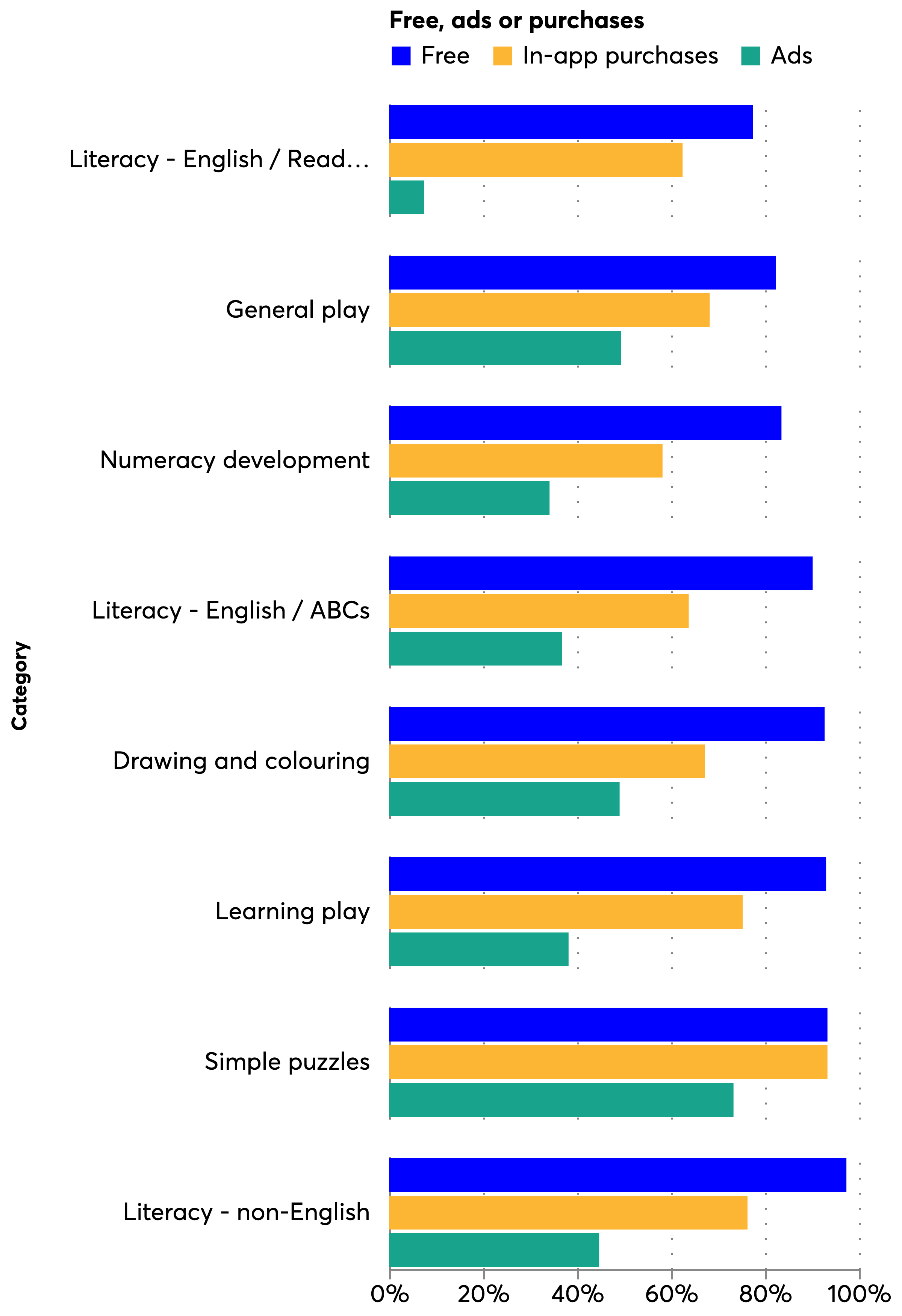

While the vast majority (88%) of toddler apps in our sample are free to download, most of them also include advertisements or in-app purchases that either unlock certain features or remove the adverts. Overall, about 70% of apps for children have in-app purchases, with some variation depending on the app category. About 60% of apps in the ‘reading and stories’ category have in-app purchases, whereas this is 90% for apps in the ‘simple puzzles’ category.

The ‘simple puzzles’ category also has the highest number of apps with ads (73% of the apps), followed by the ‘drawing and colouring’ category (50%).

By analysing more closely the content of app reviews, we found that parents’ dislike of in-app purchases and adverts is a prominent topic. Ads are particularly frustrating in toddlers’ apps, where the child might accidentally click on the ad and get taken away from the activity. This suggests that free content that removes the distraction of adverts is particularly valuable to families.

While most apps are free, the majority of apps have in-app purchases.

Are early years apps here to stay?

The global ‘app economy’ appears to be doing well, with people installing more apps than ever before, and consumer spending in apps reaching record amounts.

As a proxy of toddler app performance over time, we looked at the number of reviews posted on the Play Store. We found a large spike in Play Store reviews in April 2020 at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic. By the end of 2021, the number of reviews was still 100% higher compared to pre-pandemic levels. This echoes other observations of increased children’s screen time during the pandemic (Ribner et al., 2021).

When breaking down the rapid growth of user reviews between 2019 to 2020 we found that play-oriented apps showed the most substantial growth, and particularly apps for ‘learning play’ received 370% more reviews in 2020 compared to 2019. Apps for reading stories while modest in absolute numbers also showed a large relative growth (190%). These trends suggest that there might be a higher demand for educational games (which may be more entertaining for children) rather than apps strictly for learning.

Number of reviews and growth between 2019 and 2020

Conclusion

Nesta’s analysis of apps on the Play Store shows that apps for young children (aged 0–5) are a large and growing market. We identified almost 900 commercially available apps for pre-schoolers, and our analysis suggests that usage of toddler apps increased substantially during the Covid-19 pandemic and has remained high. This trend towards toddler tech should be considered as part of the UK early years sector’s thinking about strategies to close the school readiness gap.

UK pre-schoolers are now watching an average of three hours of videos a day (Kidscreen, 2021). This presents an opportunity to go with the grain of toddlers’ screen use to some extent, and consider how young children's screen time could be used more productively. Clearly, how young children spend their time when they are using screens matters. Steering children towards apps that offer an educational benefit may be particularly important for children from low-income backgrounds, who tend to spend more time on digital devices than their peers (Hendry et al., 2022). Improving the quality of screen time could be an opportunity to positively influence their development.

We know from surveys with parents that many are intentionally using digital devices with their young children to help them develop their literacy and numeracy (DfE, 2019). This is a goal that the UK early years sector could usefully collaborate with parents on. Some key opportunities to explore, which could potentially play a role in closing the school readiness gap for disadvantaged children, include:

- Improving the quality of toddler tech: content developed for pre-schoolers, including programmes and interactive apps, is not all of equal value. There is an opportunity to work with commercial developers to improve the educational quality, and interactivity of content aimed at young children. This might include tweaks to design to encourage co-viewing and interaction with parents and carers, to increase the benefits of screen time for children.

- Helping parents to navigate a crowded market: at the moment parents are relying on word-of-mouth recommendations and their own search of app stores. Parents need more help to identify the videos, games and apps that are most likely to benefit their children’s development, as well as keeping them entertained. Guidance for parents is a start, but tech companies and early years services could play a more active role in helping to signpost parents to higher quality digital content.

- Making high quality content freely available to low-income families: most UK parents are not spending money on the apps they download for their pre-schoolers, and they are frustrated by the adverts and in-app purchases included within many free-to-download apps for children. More high-quality, free content needs to be made available to parents of young children; this will be particularly important for lower-income families.

- Developing the evidence base for how toddler tech can be used most effectively to boost children’s outcomes: the impact of digital content designed for pre-school aged children is an under-researched area. There is an opportunity to learn more about how the screen time of pre-school children (aged 0–4) can benefit their social, emotional and cognitive development and help to boost school readiness for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Finally, it remains the case that regardless of screen time, high-quality interactions with caregivers will continue to be the most important for children’s development. In our companion piece on parenting tech, we explore the potential role of digital tools for giving parents guidance on how they can support their children’s development.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Nazli Durusut, Rachel Parker and Jack Rasala for their help in reviewing the data-driven categorisation of toddler and parent apps. Thanks also to Callum O’Mahony for his evidence review on screen time.

We thank Eva Bee for the illustration, Cara Sanquest for giving advice on the communications strategy, Siobhan Chan for editing and designing this article, as well as Celia Hannon and Raj Chande for providing insightful comments throughout the project.

Carrying out the data analysis for this project would not have been possible without the availability of high-quality, open-source code libraries of the Python scientific computing ecosystem. In particular, we express our utmost gratitude to all the maintainers, contributors and supporters of the Google-Play-Scraper package.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics ‘Guidelines for media use’, as cited in American Psychological Association (2019) Media use in childhood: Evidence-based recommendations for caregivers.

- Barr, R., Lauricella, A., Zack, E., & Calvert, S. L. (2010). Infant and early childhood exposure to adult-directed and child-directed television programming: Relations with cognitive skills at age four. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly (1982-), 21-48.

- Batcheler, R., Ireland, E., Oppenheim, C., Rehill, J. (2022) Time for parents: The changing face of early childhood in the UK. London: Nuffield Foundation.

- Bertrand, M., & Kamenica, E. (2018). Coming apart? Cultural distances in the United States over time (No. w24771). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- DfE (2019) ‘Early years foundation stage profile results: 2018 to 2019’

- DfE (2019) Childcare and early years survey of parents in England, 2019

- DfE (2020) Press release: Early years apps approved to help families kick start learning at home.

- Garrison, M. M., & Christakis, D. A. (2012). The impact of a healthy media use intervention on sleep in preschool children. Pediatrics, 130(3), 492-499.

- Guardian (2021) ‘Concerns grow for children’s health as screen times soar during Covid crisis’ by Linda Geddes and Sarah Marsh

- Hendry, A., Gibson, S. P., Davies, C., Gliga, T., McGillion, M., & Gonzalez‐Gomez, N. (2022). Not all babies are in the same boat: Exploring the effects of socioeconomic status, parental attitudes, and activities during the 2020 COVID‐19 pandemic on early Executive Functions. Infancy, 27(3), 555-581.

- Herodotou, Christothea (2018). Young children and tablets: A systematic review of effects on learning and development. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(1) pp. 1–9.

- Kidscreen (2021) ‘Preschoolers Don’t Need Parents To Find Content’ by Elizabeth Foster

- Kim, J., Gilbert, J., Yu, Q., & Gale, C. (2021). Measures matter: A meta-analysis of the effects of educational apps on preschool to grade 3 children’s literacy and math skills. AERA Open, 7, 23328584211004183.

- Lin, L. Y., Cherng, R. J., Chen, Y. J., Chen, Y. J., & Yang, H. M. (2015). Effects of television exposure on developmental skills among young children. Infant behavior and development, 38, 20-26.

- Linebarger, D. L., & Walker, D. (2005). Infants’ and toddlers’ television viewing and language outcomes. American behavioral scientist, 48(5), 624-645.

- Linebarger, D. N., Brey, E., Fenstermacher, S., & Barr, R. (2017). What makes preschool educational television educational? A content analysis of literacy, language-promoting, and prosocial preschool programming. In Media exposure during infancy and early childhood (pp. 97-133). Springer, Cham.

- Madigan, S., McArthur, B. A., Anhorn, C., Eirich, R., & Christakis, D. A. (2020). Associations between screen use and child language skills: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics, 174(7), 665-675.

- Mares, M. L., & Pan, Z. (2013). Effects of Sesame Street: A meta-analysis of children's learning in 15 countries. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 140-151.

- Marsh, J., Plowman, L., Yamada-Rice, D., Bishop, J.C., Lahmar, J., Scott, F., Davenport, A., Davis, S., French, K., Piras, M., Thornhill, S., Robinson, P. and Winter, P. (2015) Exploring Play and Creativity in Pre-Schoolers’ Use of Apps: Final Project Report

- Meyer, M., Zosh, J. M., McLaren, C., Robb, M., McCaffery, H., Golinkoff, R. M., ... & Radesky, J. (2021). How educational are “educational” apps for young children? App store content analysis using the Four Pillars of Learning framework. Journal of Children and Media, 15(4), 526-548.

- Ofcom (2022) Children and parents: media use and attitudes report 2022.

- Outhwaite, L., Early,E., Herodotou, C., & Van Herwegen, J., (2022) Can Maths Apps Add Value to Young Children’s Learning? A Systematic Review and Content Analysis. UCL & Nuffield Foundation.

- Ponti, M., Bélanger, S., Grimes, R., Heard, J., Johnson, M., Moreau, E., ... & Williams, R. (2017). Screen time and young children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatrics & Child Health.

- Ribner, A. D., Coulanges, L., Friedman, S., Libertus, M. E., Hughes, C., Foley, S., ... & Silver, A. (2021). Screen Time in the Coronavirus 2019 Era: International Trends of Increasing Use Among 3-to 7-Year-Old Children. The Journal of pediatrics, 239, 59-66.

- Wen, L. M., Baur, L. A., Rissel, C., Xu, H., & Simpson, J. M. (2014). Correlates of body mass index and overweight and obesity of children aged 2 years: findings from the healthy beginnings trial. Obesity, 22(7), 1723-1730.

Methodology

We sampled the apps by combining manual search, crowdsourcing and recursive search (‘snowballing’). The manual search was performed in January 2022 by exploring UK Play Store app categories for Parenting, Education, and Ages up to 5. The Play Store applies a consistent template across categories, allowing users to browse the Top Free, Top Grossing, Trending, and Top Paid apps within each category, and each of these filters will show up to 200 apps. We crowdsourced additional apps by consulting our colleagues about the apps they used when they had young children. For the recursive search, we leveraged the fact that most apps on the Play Store have about five listed related apps. For each app that we identified in the manual and crowdsourcing steps, we selected the apps related to them and then repeated this four more times. The total sample included about 3,900 apps that we reviewed and narrowed down to about 1,200 relevant apps.

While we sampled apps from the UK version of the Play Store, the number of installations and reviews as retrieved by the Google-Play-Scraper library reflect global figures. The app scores, however, are more specific to the location and reflect user preferences in the UK.

Overall, this sampling approach can be viewed as a thorough search of the Play Store, but it might still overlook very recent apps that have a small number of ratings or installations. This might explain the drop in the number of released apps in 2021. Also note that we are only able to sample apps that are presently on the Play Store, and therefore apps (and their reviews) that were removed from the Play Store before January 2022 do not appear in our results. As older, inactive apps might be taken off the Play Store, we are likely to increasingly underestimate the real number of released apps in years further in the past. Therefore, we focus on comparing trends across different categories, such as comparing apps for children and apps for parents.

Our app categories were inferred by calculating numerical representations of the app description texts (so-called sentence embeddings) and applying the HDBSCAN clustering algorithm on these representations. The automatic cluster assignments were manually reviewed and adjusted.

To uncover additional trends in the toddler and parenting tech space, we also analysed data from the Crunchbase business information platform.

The analysis code is available in the project’s GitHub repository.

Contact the authors via louise.bazalgette@nesta.org.uk and karlis.kanders@nesta.org.uk.