Why do the early years matter so much for later life?

The early years are a crucial period in which the foundations of physical, cognitive, emotional and social development are laid.

This explainer unpacks the evidence as to why this is true, drawing on insights from neuroscience, psychology, economics and public health. We explain some of the evidence around how early experiences affect brain development, what happens during sensitive and critical periods, and why supporting children's early years represents both a smart economic investment and a moral imperative. Understanding these foundations can help us design more effective programmes and policies that give every child a fairer start in life.

Research shows the early years matters

We know that a child’s early experiences can predict their longer-term outcomes. In the UK, children with stronger cognitive and socio-emotional skills at age five are significantly more likely to have a higher education, higher income and better health at age 42. This doesn’t necessarily mean that a person’s early experiences determine their lifecourse – of course correlation does not always mean causation. But we know from a large body of international research that there is a causal link.

Research shows that providing the right support to families when children are young can have long-term impacts. For example, economists have tracked outcomes for children who received specific types of support, such as financial support or early education. They find that children who received this support early in life had better outcomes decades later – in terms of earnings, health and life expectancy – than they would have had if they didn’t receive that support. From a public finance perspective, this kind of early support can even pay for itself, because it means lower healthcare costs and higher income tax receipts.

But this historical evidence from policy and economic research doesn't stand alone. As we explain below, it's reinforced by findings from neuroscience that show why early childhood is so influential.

This neuroscientific evidence aligns with findings from developmental psychology showing how early attachment and interactions shape social-emotional development, and with epidemiological research demonstrating links between the mother’s stress levels in pregnancy and the child’s mental health years later. When multiple independent fields of study all point to the importance of the early years, it creates a particularly robust and compelling case for focusing on early childhood development.

How children’s brains are shaped by early experiences

Within a child’s early years, neuroscientists identify both 'sensitive' and 'critical' periods in brain development. Sensitive periods represent windows when particular skills are most readily acquired, as the brain forms and strengthens neural connections (called ‘synapses’) in response to specific experiences. During critical periods, certain experiences must occur for normal development. The timing of these sensitive and critical periods is different for different brain functions.

The developing brain initially creates an abundance of synapses in the first two years of life, and then refines them through a process called synaptic pruning. Connections that are frequently used become stronger, while unused ones are lost – "use it or lose it" is a fundamental principle.

What do we mean by the ‘early years’?

This period starts at the beginning of pregnancy until age five. During this period, a child's brain develops rapidly – by age six, the brain has reached about 90% of its adult size.

There is a lot of focus on the first 1000 days – from conception to age two – in policy circles. This focus originated from research on nutrition and stunting – showing that the effects of poor nutrition in infancy are irreversible after age 2. As we describe above, this period is also particularly significant for brain development. However, emerging research suggests that the ‘next 1,000’ days (ie, ages 3-5) are equally important for child development – but for different reasons.

Language acquisition offers a clear example: between 6-12 months, babies can distinguish between all speech sounds from any language.

Without exposure to particular sounds during this time, the neural circuits dedicated to processing those sounds are repurposed.

By a child’s first birthday, they begin to specialise in recognising sounds from languages they regularly hear, while losing the ability to distinguish between similar sounds in unfamiliar languages.

Research by Werker and Hensch demonstrated this with bilingual infants: babies exposed to two languages maintain neural pathways for processing both sets of language sounds, while monolingual infants showed pruning of unused sound distinctions, resulting in a specialised but narrower linguistic capacity.

Early development is complex and interconnected

Given what we know from neuroscience, we may wonder – can we “engineer” the brain to provide the right inputs at the right time for optimal development? However, the evidence points to a more nuanced understanding of how we apply the science. Development is fundamentally interconnected: cognitive, social-emotional, physical, and language domains constantly influence one another in a complex web of interactions. What’s more, children are interconnected with their parents, families and communities.

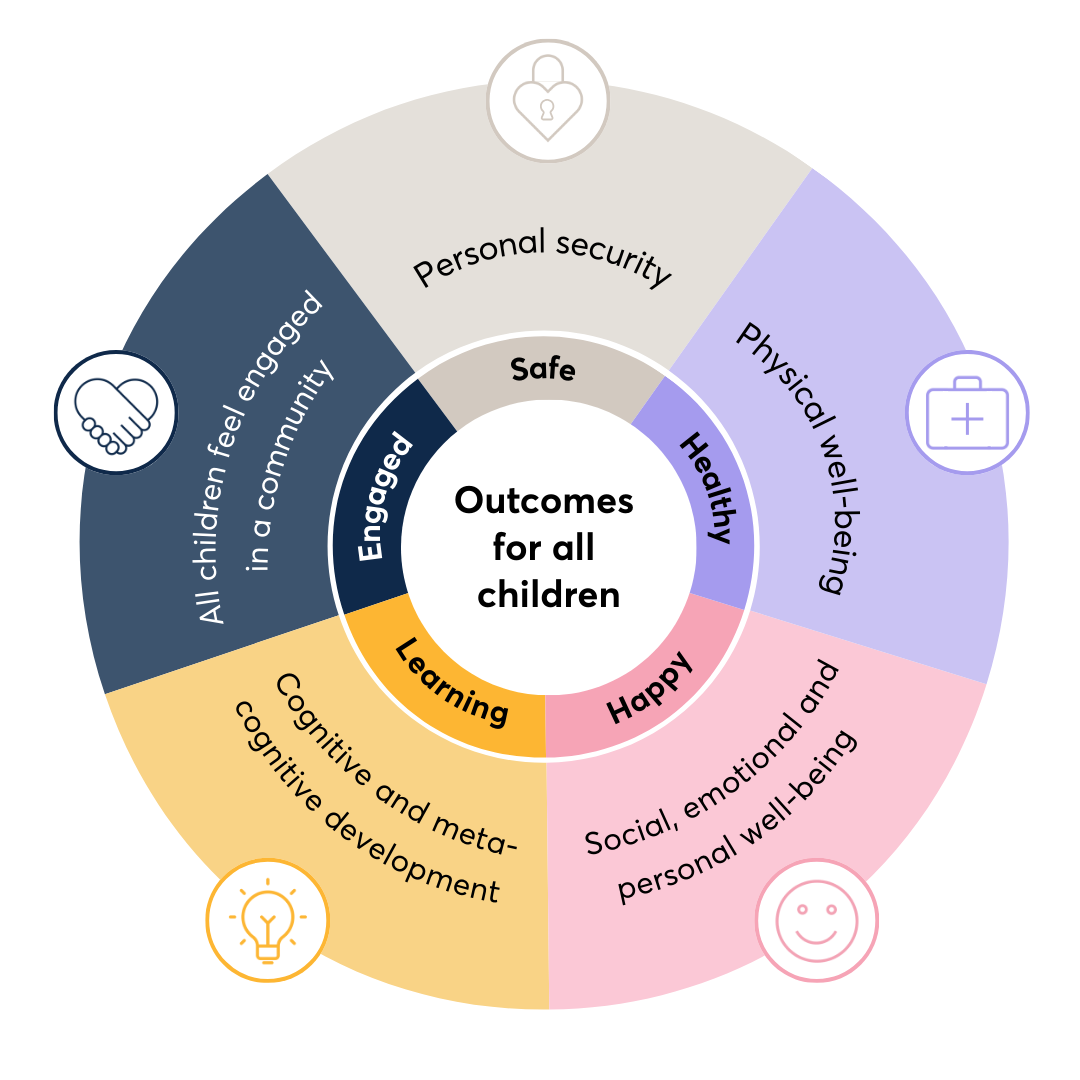

Attempting to isolate and prioritise one aspect over others risks overlooking this essential interconnectedness. Instead, frameworks like the Common Outcomes Framework offer a more holistic approach, recognising that children's wellbeing encompasses multiple dimensions: being safe, healthy, happy, learning, and engaged. This integrated perspective better reflects the reality of child development and provides a more comprehensive foundation for supporting children's flourishing across all domains.

Early experiences matter – remembered or not

Early childhood is a period of rapid brain and body development, and early experiences can impact this development – even when the child does not consciously remember them. This is because the effects occur at neurobiological and developmental levels rather than through conscious memory. For example, children who experience consistent, responsive caregiving develop stronger neural pathways for emotional regulation, even though they won't explicitly recall the thousands of individual interactions that built these pathways.

Beyond this direct impact on brain architecture, early experiences can influence development through two key mechanisms.

First, through physiological effects that alter gene expression – a process known as epigenetics. Scientists now know that children’s development is not driven by nurture or nature – it’s the combination of the two.

The interplay between our genes (‘nature’) and environment (‘nurture’) occurs throughout life – every day our diet, exercise and interactions affect our gene expression.

But epigenetics is particularly influential during pregnancy and early infancy, when growth is most rapid.

For instance, studies have shown that maternal malnutrition and stress during pregnancy can both activate genes that increase chronic disease risk, and permanently affect a child's developing immune system.

Early experiences matter – remembered or not

Early childhood is a period of rapid brain and body development, and early experiences can impact this development – even when the child does not consciously remember them. This is because the effects occur at neurobiological and developmental levels rather than through conscious memory. For example, children who experience consistent, responsive caregiving develop stronger neural pathways for emotional regulation, even though they won't explicitly recall the thousands of individual interactions that built these pathways.

Beyond this direct impact on brain architecture, early experiences can influence development through two key mechanisms.

First, through physiological effects that alter gene expression – a process known as epigenetics. Scientists now know that children’s development is not driven by nurture or nature – it’s the combination of the two.

The interplay between our genes (‘nature’) and environment (‘nurture’) occurs throughout life – every day our diet, exercise and interactions affect our gene expression.

But epigenetics is particularly influential during pregnancy and early infancy, when growth is most rapid.

For instance, studies have shown that maternal nutrition and stress during pregnancy can both activate genes that increase chronic disease risk, and permanently affect a child's developing immune system.

Second, early experiences may have ‘cascade’ effects – that is, chains of events where early experiences set the stage for subsequent development. A compelling example comes from research on ear infections.

Second, early experiences may have ‘cascade’ effects – that is, chains of events where early experiences set the stage for subsequent development. A compelling example comes from research on ear infections.

Untreated ear infections in early childhood can temporarily impair hearing, delaying language acquisition.

This delayed language acquisition can lead to behavioural difficulties as children are less able to express themselves in words.

When children start school, behavioural difficulties mean it is harder for teachers to engage them, and this ultimately affects academic performance.

It is not that ear infections directly affect academic performance, rather a cascade where one developmental domain affects another in sequence.

Another example comes from children’s early relationships with their caregivers – some research suggests this can have cascade effects, affecting the strength of their friendships after they start school.

This understanding of the different ways in which early experiences can shape development pathways helps explain why early childhood is so influential for lifelong wellbeing, regardless of whether those experiences remain in conscious memory.

Early years are important, but not deterministic

Early childhood does influence life chances, but no-one’s future is predetermined. While early childhood is crucial for development, our brains remain adaptable throughout our lives, and protective factors do make a difference in reducing the consequences of early struggles. Going back to our example above on language learning: it's easier to become fluent when you start young, but people can and do successfully learn new languages as adults – it just takes more effort and support.

Our brains retain the ability to adapt, learn, and build new capabilities later in life. Indeed, other developmental windows open later in life. Adolescence, for instance, represents another period of significant brain reorganisation and heightened sensitivity for the development of social cognition, identity formation, and executive function. These later sensitive periods offer additional opportunities for positive development and intervention.

What's more, even when early adversity does affect development, research shows that targeted interventions can help children overcome these challenges. For example, scientists have known for some time that exposure to high levels of lead in early childhood can damage children’s brain development.

In a landmark study, Billings and Schnepel found that children who experienced early brain damage due to lead exposure but received appropriate interventions performed significantly better at school than those who had milder damage – and hence did not qualify for the additional support. Although the physiological effects of lead exposure remained, the intervention helped children develop strategies to work around these constraints.

From an economic perspective, early intervention is often more cost-effective than later remediation. For example, Nobel laureate James Heckman's research demonstrates that an early education programme in the US has yielded returns of 7-10% per year, through improved outcomes and reduced need for special education, healthcare, and criminal justice services. This kind of early investment is smart public policy.

Strong foundations support success at school

The school system works hard to give all children an equal chance – but the foundations that let children thrive at school are laid in the pre-school years. While schools play a vital role in children's development, by the time children start school at age four or five, significant developmental gaps have already emerged. Research shows that children in England from disadvantaged backgrounds are already, on average, five months behind their peers in language and social skills when they start school.

We know that inequalities can compound over time. When children start behind at school, they may fall further behind. But the opposite is also true – when we successfully support early development, we see benefits that multiply over time. For example, disadvantaged children who took part in the Preparing for Life programme at ages 0-5, which was run in Dublin, performed better on school tests at age nine .

Nobel laureate James Heckman describes this through the concept of "self-productivity" – the idea that skills beget skills. Capabilities developed in early childhood become crucial tools for developing new capabilities later. This creates a multiplier effect where early advantages (or disadvantages) compound over time.

Think of it like building a house: schools can add extensions and improvements, but they're working with the foundation that was laid in the early years. While good schools can and do help children progress, they find it much harder to rebuild shaky foundations than to build on solid ones. Extending this analogy to adulthood: if a house is built on shaky foundations, it might keep standing for a time, but it will be much less resilient to an unlucky storm than a house built on solid foundations.

It is true that some inequalities will emerge later, even if we were able to eliminate inequalities at school starting age. But early intervention lays the groundwork that makes all other efforts to promote equality more effective. It is one of our most powerful tools for promoting more equal life chances.

Conclusion

No-one’s future is predetermined – learning and development continue throughout life, and effective interventions can help at any age. That said, early childhood offers a unique window of opportunity to set children on positive developmental trajectories. The brain's exceptional plasticity during these years, combined with cascading effects that ripple through later development, means that early experiences have outsized influence on long-term outcomes.

The science and economic evidence is compelling, but the importance of early childhood extends beyond this. Supporting young children is fundamentally about upholding their basic rights to health, education, and the opportunity to fulfil their potential – rights enshrined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. It's about ensuring that all children, regardless of the circumstances of their birth, have a fair chance to thrive.