Where you live shouldn’t stop you accessing the very best childcare – but in some places it does

By Lauren Orso, Laura Jones, Sarah Cattan, Vivek Roy-Chowdhury, Cara Sanquest

25 September 2024

Looking into Ofsted's latest data on childcare providers and inspections we discovered a critical issue in England's childcare sector that is being overlooked: the unequal access to high-quality childcare.

We already know that the availability of childcare places across the country is insufficient and uneven. Recent analysis from RAND found the existence of ‘childcare deserts’ – areas where demand for childcare significantly outstrips the supply. According to this research, approximately 44% of children live in these deserts, which are more likely to be found in areas of deprivation.

But it's not just about whether there are enough childcare places available but also whether those places are high quality enough.

Ofsted rates childcare – at nurseries and childminders alike – in a similar way to schools: inadequate, requires improvement, good and outstanding. Although the government plans to scrap these single-word assessments eventually, right now they reveal a worrying picture of uneven and unequal access to the very best childcare provision.

Our data dive into the latest statistics found that:

1. There has been a decrease in both the number of providers and the proportion that are high-quality:

- There’s been an overall decline in the number of childcare providers, mainly driven by a 5% fall in the number of childminders, compared to just a year ago.

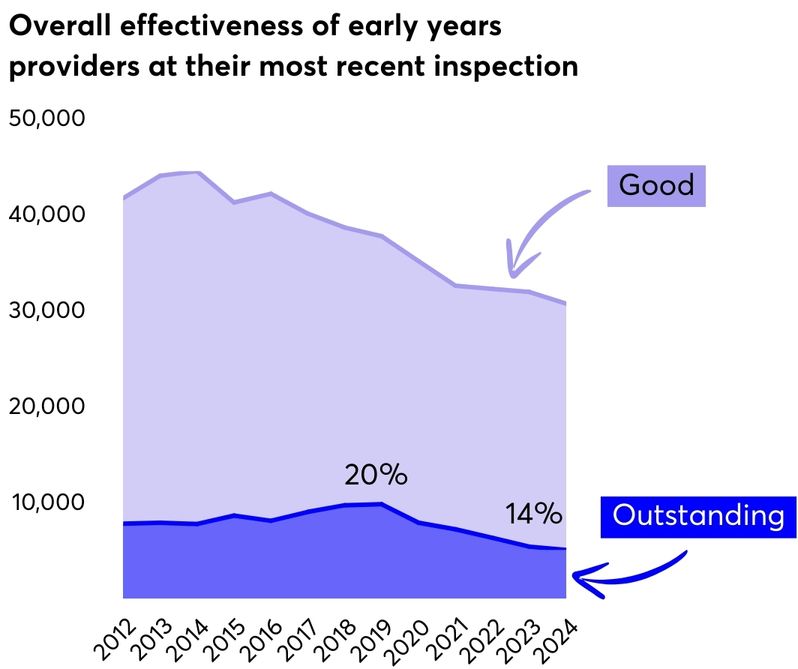

- Out of those remaining, a declining share are achieving an outstanding Ofsted rating. The total number of childcare providers rated as outstanding has decreased from over 9,000 (20% of providers) in 2019 to just over 5,000 (14% of providers) in 2024.

- This declining number is due to providers subsequently being rated below outstanding, as opposed to outstanding providers leaving the market.

2. There are proportionately fewer outstanding childcare places available in socioeconomically deprived areas:

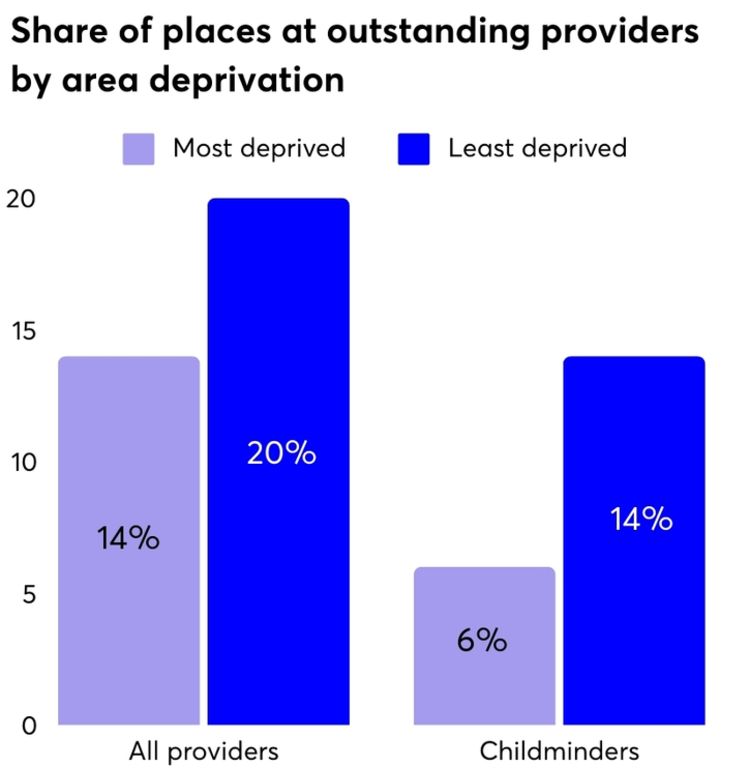

- The share of places at outstanding providers in the most deprived areas is 14%, compared to 20% in the least deprived areas.

- This is being driven primarily by disparities in childminding – which account for one in eight places on the early years register. Only 6% of places at childminders in the most deprived areas received an outstanding rating, compared with 14% in the least deprived areas.

3. These factors mean that there are significant variations in the proportional availability of the highest-quality childcare across England:

- For every 1,000 children, the number of childcare places in settings judged outstanding varies considerably. By local authority, Kensington and Chelsea has 104 outstanding places for every 1,000 children – the highest number in England – whereas Rutland has none.

Distinctions between 'good' and 'outstanding' childcare settings

The UK government has begun phasing out single-word Ofsted ratings for schools, set to be replaced by report cards by 2025, while the timeline for implementing similar changes for early years settings is expected within the next year. Until now, these ratings have been the primary way parents assess the quality of settings.

An 'outstanding' rating from Ofsted signifies that a childcare setting not only consistently meets the high standards of a 'good' rating but also demonstrates exceptional quality across all areas of provision. While a 'good' setting effectively implements a well-planned curriculum and fosters positive learning behaviours, an 'outstanding' setting distinguishes itself through the exceptional impact its curriculum has on children's learning, evident in their deep engagement and high levels of achievement.

‘Outstanding’ settings provide highly effective professional development for practitioners, ensuring they have the skills and knowledge to deliver exceptional teaching and support children's learning to the fullest.

More detail can be found in the Early years inspection handbook.

Why the quality of childcare matters

Research has found that early education and care can have a positive effect on children’s cognitive, behavioural and social outcomes. There is evidence that spending more time in a nursery rated ‘outstanding’ improves children’s chances of achieving both the expected and higher levels of attainment at the end of Reception, whereas no such effects were found for those attending nurseries rated ‘good’.

However, while there is a positive correlation between outstanding Ofsted ratings and children's attainment at age 5, the research has not yet established a definitive causal link. Other background factors, such as parental engagement etc, could also be at play.

Despite this, it is still worthwhile to analyse the availability of outstanding childcare places in relation to deprivation. At present this is the best data available and the evidence shows that for disadvantaged children there are associations between attending higher-quality formal group early childhood education and care and better socio-emotional outcomes at age 5.

Why are the number of outstanding childcare providers falling?

The number of outstanding providers has almost halved since 2019 and now stands at 1 in 7.

For some time now, almost all settings have managed to be judged good or higher – 97% according to their most recent inspection.

However, after a few years of growth, there’s been a drop in the percentage of outstanding providers since 2019 – it’s now down to 14% from 20%.

Although the numbers show a decline in the overall number of childcare providers, this isn’t what is driving the decline in the number of outstanding providers.

Rather than outstanding providers leaving the market, it appears that in fact many more outstanding providers have since been re-rated as good.

How much difference does living in an area of deprivation make?

The Ofsted data allocates childcare providers to one of five deprivation bands – making it possible to cross-reference the share of places with outstanding providers with an area’s socio-economic profile. Our analysis found that the share of outstanding places in the most deprived areas is 14%, compared to 20% in the least deprived areas.

We know that children living in affluent areas are more likely to reach a good level of development than their peers in deprived areas. In the 2022/23 school year, in the most deprived areas, 67.2% of children reached a good level of development compared to 76.6% of children in the least deprived areas. Together, this suggests this gap may be partly explained by differences in the availability of outstanding childcare across parts of England.

The type of childcare provision makes a big difference – and childminding is the overlooked setting

The percentage of childcare places at childminders rated as outstanding varies significantly depending on the level of socioeconomic deprivation in the area.

Most childcare places are provided by facilities in one of two categories: childcare on non-domestic premises or childminders. Childminders use their own homes to look after children (either independently or through an agency) whereas childcare on non-domestic premises includes nurseries, pre-schools, holiday clubs, and other group-based settings.

We were able to compare each of these provider types, their Ofsted ratings and deprivation levels. This is what we found.

Breaking down the providers revealed a trend hidden by the headline numbers. The chart above illustrates that for childcare in non-domestic settings, the percentage rated as outstanding decreases as the level of area deprivation increases – but only slightly.

In the most deprived areas, 11% of places at these providers are rated as outstanding, slightly increasing to 14% in the least deprived areas. This actually suggests a relatively uniform standard of care despite any differences in deprivation.

But for childminders it’s a much starker story.

Childminders, which account for 13% of childcare places on the early years register, show a much more pronounced variation in outstanding ratings based on area deprivation.

Only 6% of places at childminders in the most deprived areas received an outstanding rating, in contrast to 14% in the least deprived areas. This disparity points to the impact of socio-economic factors on the quality of home-based childcare – possibly influenced by differences in resources, support, and training opportunities available to childminders in more affluent areas compared to less affluent ones.

How much does access to high-quality childcare vary depending on where you live?

Looking at the number of childcare places that are rated outstanding at local level, we could see that the availability of high-quality childcare places varies considerably between local authorities in England.

Firstly, in each local authority in England we compared the percentage of places available at outstanding providers to the total number of childcare places at settings with an Ofsted judgement.

Although the total percentage of places rated outstanding nationally is 14%, the percentage locally didn’t always reflect that. The North East had the highest percentage of places rated outstanding and the East Midlands the lowest.

To understand where children were more likely to be able to attend high-quality education and care, we mapped the number of places available in outstanding settings, relative to the local child population.

|

Rank |

Local authority |

Outstanding places for every 1,000 0-5 year olds |

Rank |

Local authority |

Outstanding places for every 1,000 0-5 year olds |

|

1 |

Kensington and Chelsea |

104 |

140 |

Wolverhampton |

13 |

|

2 |

South Tyneside |

94 |

141 |

Hartlepool |

12 |

|

3 |

Trafford |

92 |

142 |

Lincolnshire |

11 |

|

4 |

York |

91 |

143 |

Croydon |

10 |

|

5 |

Cambridgeshie |

84 |

144 |

Derby |

10 |

|

6 |

Warrington |

84 |

145 |

Redcar and Cleveland |

9 |

|

7 |

Calderdale |

83 |

146 |

Nottingham |

8 |

|

8 |

Brighton and Hove |

81 |

147 |

Newham |

6 |

|

9 |

Westminster |

77 |

148 |

Blackpool |

3 |

|

10 |

Leeds |

74 |

149 |

Rutland |

0 |

The table shows the top and bottom ten local authorities in England by the number of places at providers rated outstanding for every 1,000 children aged 0-5.

It tells us that there are very stark disparities in the availability of high-quality childcare across parts of England.

A child growing up in an area like Kensington and Chelsea has over 10 times the number of outstanding places available to them as in an area like Derby.

How can the gap in childcare quality be bridged?

The new UK Government has promised to break down barriers to opportunity, and the new Education Secretary has signalled that the early years will play a strong part in achieving the government’s opportunity mission. Ensuring that families have access to high-quality childcare they can afford would be crucial to achieving this.

However, the government will face huge challenges in delivering the expansion of the free entitlement to children of working parents from the age of 9 months, a policy inherited from the previous Conservative administration which they remain committed to.

The uneven availability of childcare, vividly illustrated by the childcare deserts discussed earlier, and the unequal quality of available places are exacerbated by a reduction in both the number and quality of providers. This likely reflects the pressures of delivering high-quality early education in the current environment. Together, these factors create serious barriers to achieving the government’s stated aims.

We have shown that these trends are particularly acute for childcare spots at childminders. They are serving a small but still important share of the market and shouldn’t be overlooked. Childminders could play an important role in providing childcare for very young children, as well as wraparound care, if provision through state nurseries is increased. This will raise important questions for what kind of role the government wants this part of the market to play in achieving its goals.

Early childhood education and care can have a positive effect on children’s behavioural, cognitive and social outcomes, particularly if it is of high quality and particularly for disadvantaged children.

Nesta’s fairer start mission aims to eliminate early childhood inequalities by 2030, with a focus on improving and providing access to high-quality early childhood education and care.

If the Government is serious about breaking down barriers to opportunity from the very early years too, we have shown that it is not just the availability of childcare but the availability of high-quality childcare that is crucial. That will require strategic thinking about how to raise quality in every part of the childcare market – childminders included.