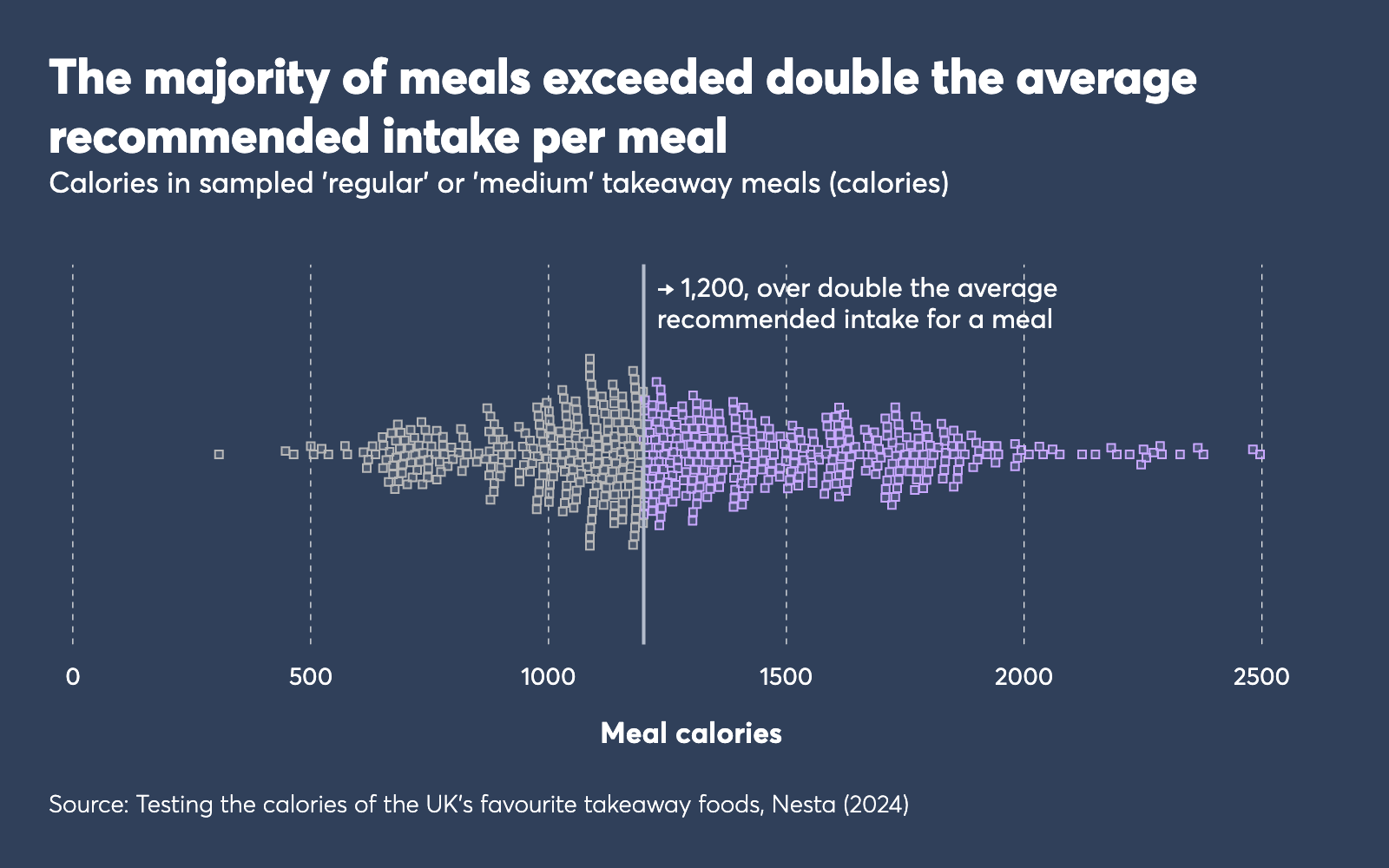

How to read this chart: The ten types of meals sampled are positioned on the vertical axis. Each square represents a sampled meal, positioned on the horizontal axis according to its calorie content.

Data collection

600 samples were collected from 10 popular meals across five cuisine types in six UK cities. These were then packaged and sent to an accredited lab for calorie and nutritional analysis.

Key findings

- Across all cuisines, meals contained an average of 1,289 calories.

- 99% of meals exceeded the recommended calorie intake of 600 kcal per meal, 57% exceeded double the average recommended intake per meal (1200 calories), and 2% exceeded the recommended daily intake of 2,250 kcal (for females this is 2,000; for males 2,500).

- Despite only sampling meals listed as 'regular' or 'medium' portions, the calorie content of each meal varied widely (for instance a ‘regular' or 'medium' pepperoni pizza purchased for this research contained between 600 and 2,300 calories).

- More expensive meals had a higher number of calories, even after adjusting for differences in portion size (in grams).

Methodology and further results can be found in the technical appendix.

Filling an evidence gap 🔍

To improve our health, we need to make it easier to enjoy healthier food from our local takeaway businesses. Obesity is a serious and increasing problem in the UK, affecting our health, wellbeing, productivity and incurring significant costs to the NHS and wider society.

It is, however, solvable. A reduction of 216 calories per person per day in the diets of those living with excess weight could lead to a halving of obesity prevalence.

The out-of-home (OOH) sector is a key component of our food environment and contributes around 300 calories per person per day on average to our national diet. Fast food – from both chain and independent restaurants – accounts for approximately 35% of this). Reducing calorie intake through changes in the OOH sector is therefore crucial.

We’re increasingly used to seeing calorie information in large OOH businesses due to legislation, but there’s a lack of data on calorie content from small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the sector.

This research aims to bridge this gap by analysing the calorie content of popular meals from independent takeaway businesses across Great Britain.

The key charts that lift the lid on some of our favourite takeaways

The calorie content of 'regular' or 'medium' takeaway meals varied significantly for the same dish

How to read this chart: This series of charts depicts the range of calorie content for each type of takeaway meal. The dots furthest apart represent the highest and lowest values. The white shaded boxes overlayed on the distribution represent the 25th to 75th centile range.

‘Regular' or 'medium' pepperoni pizzas purchased for this research contained between approximately 600 and 2,300 calories.

Similarly, for battered cod and chips, there was approximately a 1,300-calorie difference between the portion with the lowest and highest number of calories.

While the minimum and maximum values may be extreme outliers and not representative of the typical range of calories that people encounter, the 25th to 75th centile range captures the middle 50% of the data, offering a more reliable view of the typical variation.

All meals displayed high levels of variation in terms of calorie content, except for the single beef burger and chips, coated chicken burger and chips, and chicken chow mein, which were more consistent.

This highlights that portion sizes are not standardised across vendors, even for the same dish.

This high variation in meal calories means that the healthiness of the meal you purchase could be heavily influenced by where you eat, not just what you eat.

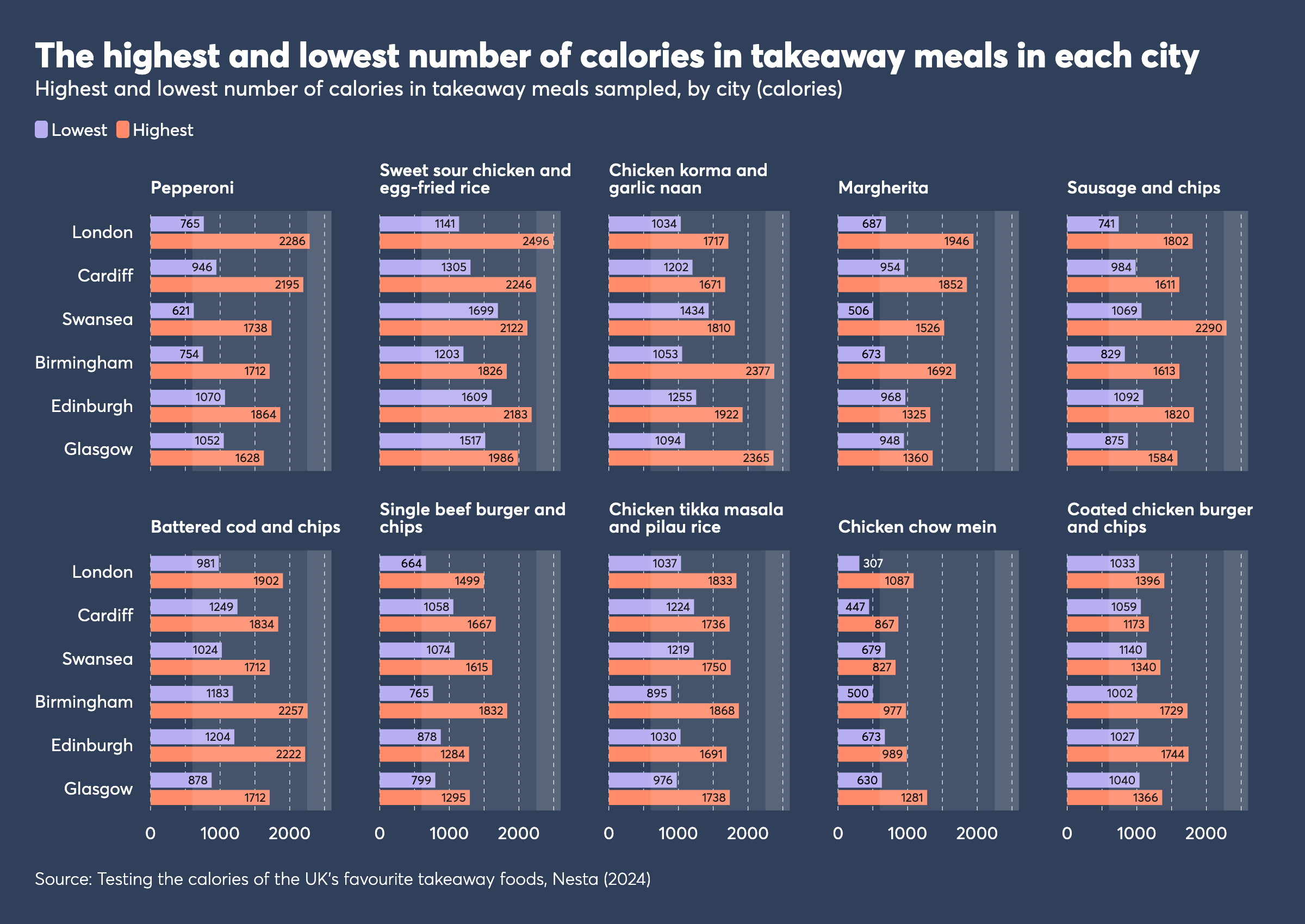

There is high variation in calorie content of 'regular' or 'medium' takeaway meals for the same dish, even within the same city

How to read this chart: This chart shows the range of calories in takeaway meals, showing the highest and lowest values for each city.

There’s significant variation between the highest and lowest calorie counts for a given meal within the same city, which is particularly relevant to local consumers.

In Cardiff, a portion of sweet and sour chicken with egg-fried rice ranged from 1,305 to 2,246 calories. In Glasgow, sausage and chips ranged from 875 to 1,584 calories. In Birmingham, chicken tikka masala with pilau rice ranged from 895 to 1,868 calories.

To put this into further context, two restaurants just a 15-minute walk from each other in Birmingham are selling 'regular' or 'medium' portions of battered cod and chips that differ by 385 calories – approximately equivalent to the combined calories of a packet of crisps and a chocolate bar.

We found that this variation in total meal calories is not explained by how socioeconomically deprived the area is where a given restaurant is located (as determined by quintiles of the indices of multiple deprivation).

This high variation in a local context means that consumers might be purchasing products of significantly different calorie content depending on which local restaurant they choose.

57% of meals exceeded double the average recommended intake per meal (1200 calories)

How to read this chart: Meals sampled are positioned on the horizonal axis according to their calorie content. Each square represents a sampled meal and are coloured by whether they exceed 1,200 calories.

It therefore seems plausible that reducing the portion size of many of these much-loved meals could increase healthiness without diminishing the enjoyment we derive from eating. For example, reducing a meal containing 1,500 kcal to 1,350 kcal represents a significant reduction in absolute calories, while the meal remains enjoyable and filling.

Defining whether a meal is ‘excessive’ requires considering what individuals eat during the rest of the day, or even the week, as well as other factors such as physical activity and BMI. One large meal might be balanced by smaller ones, meaning the total number of calories consumed over time could still fall within healthy parameters. However, while it is difficult to assess whether a meal containing 750 calories is unhealthy without knowing the rest of someone's diet, it is likely that a meal as large as 1,200 calories is excessive, as this is approximately half the recommended daily intake.

Meal portion size varied more than energy density

When it comes to cutting down on excess calories from takeaway meals, both portion size and energy density (the concentration of calories in a meal) are important.

Energy density was relatively low compared to some discretionary items commonly sold by retailers. For example, we found that a typical portion of beef burger and chips has 259 calories per 100g, while a typical 45g packet of Walker’s Ready Salted Crisps contains 518 calories per 100g.

All of this suggests that focusing on portion size reduction may be a more viable approach to reducing calorie intake in this sector than reformulating dishes to lower energy density.

Furthermore, reformulation is a technical and at times expensive process, which would be difficult for small and medium-sized businesses to achieve, whereas portion size reduction is a much easier change for a business to implement.

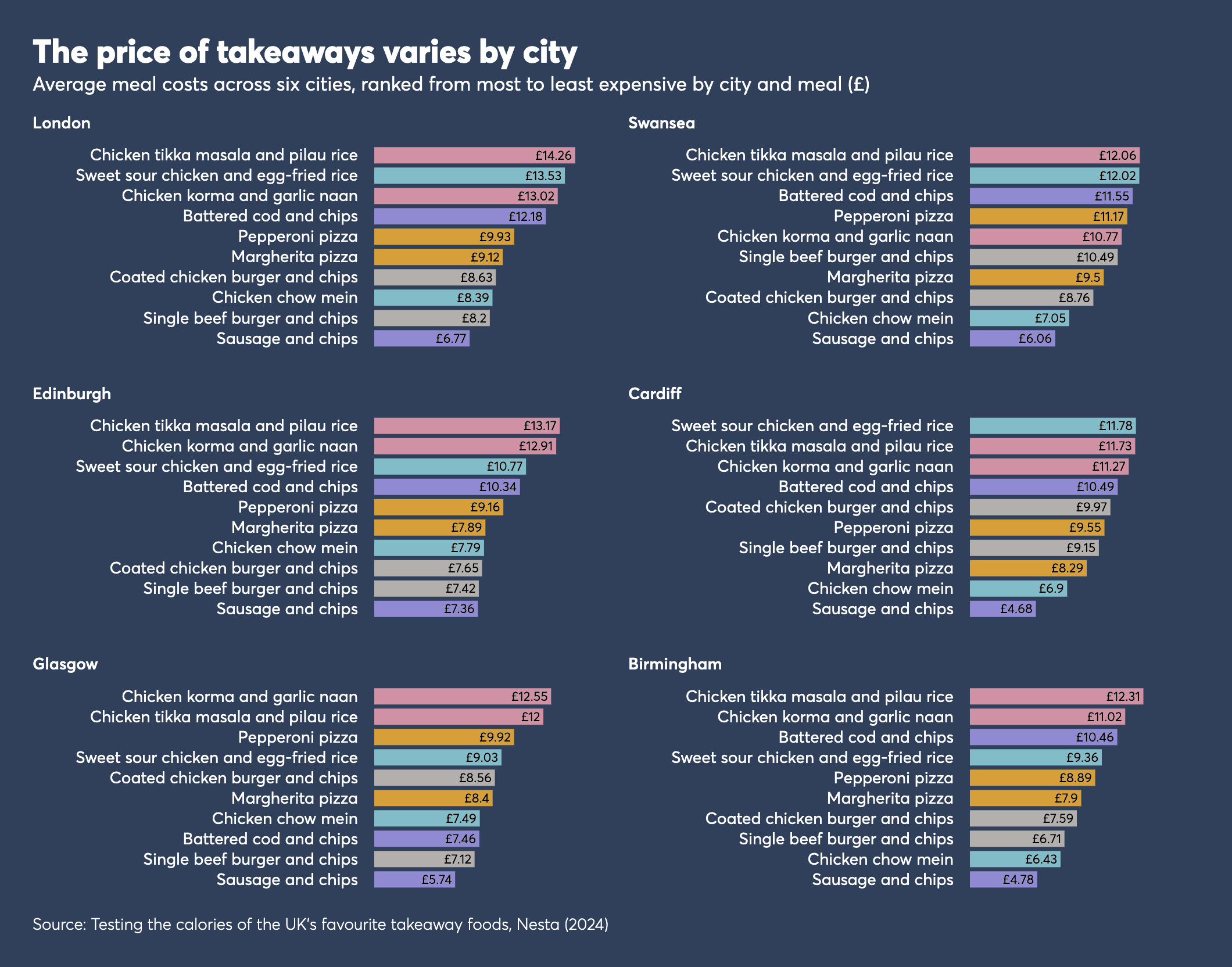

The cost of Britain's best-loved takeaways varied from city to city

How to read this chart: The average price of meals sampled in each city is displayed in descending order from the most expensive to the least expensive.

London and Swansea had some of the highest prices, whereas Birmingham and Glasgow had some of the lowest.

The dishes with the greatest price difference between cities were battered cod with chips and sausage and chips.

|

Dish |

Highest price |

Lowest price |

Difference |

|

Battered cod with chips |

£12.18, London |

£7.46, Glasgow |

£4.72 (38.8%) |

|

Sausage and chips |

£7.36 Edinburgh |

£4.68, Cardiff |

£2.67 (36.3%) |

The most consistent meal in terms of cost across cities was the margherita pizza (£7.89 - £9.50), with a variation of just £1.60 (16.9%).

Across all meals we found that more expensive meals had a higher number of calories, even after adjusting for differences in portion size (in grams).

We found that there's a clear trend showing that more expensive meals usually have more calories. A lot of this is because pricier meals tend to be larger. However, even when we take the size of the meals into account, there’s still a noticeable trend where more expensive meals generally have more calories.

This highlights that consumers might not only find healthier versions of the same meal at different outlets within the same area, but that these might be cheaper too.

What this tells us about takeaways

Many of us enjoy eating a takeaway and the chip shops, pizzerias, burger joints, chinese takeaways and curry houses in our neighbourhoods and high streets are hugely important parts of our communities and our local economies. The sector is also a significant contributor to our diets and our obesity crisis. To improve our health, we need to make it easier to enjoy healthier food from our local takeaway outlets.

This research highlights the high calorie content of some of Britain’s best-loved takeaway meals and how big variations in calories mean consumers are exposed to meals of significantly different calorie content as a result of where they live.

However, these results should give us cause for hope. Firstly, the large calorie content of many meals suggests that small ‘relative’ reductions in portion sizes could lead to a meaningful ‘absolute’ reduction in calories purchased from independent takeaways. Such small adjustments would improve the healthiness of our favourite takeaway foods without reducing the joy we derive from them.

Secondly, the large variation between different versions of the same type of meal adds weight to the potential impact of regulation aimed at smaller independent businesses as a way to incentivise them towards best practices. Voluntary regulation has not thus far been hugely impactful in the out of home space.

Nesta is continuing to produce research into the OOH sector to better understand which approaches could be taken to most effectively increase the healthiness of food products prepared and purchased outside the home.