Could new ways of paying for heat help reduce household carbon emissions?

Electrifying the way we heat our homes is an important tool in reducing our reliance on fossil gas and bringing down our carbon emissions.

However, high upfront costs, higher running costs and disruptive installation are all barriers to adoption, particularly for people with lower incomes. New ways to pay for heat are needed so that more people can reduce carbon emissions from their home.

We wanted to explore whether innovation in business models could help people overcome some of these barriers. We’ve combined research, interviews and futures thinking to explore what’s on the horizon and what would need to change to enable these models to take off.

We’ve identified five innovative business models that we think could help people to reduce their reliance on gas and oil heating and switch to low-carbon electric heating.

Home comfort contract

How might this work?

Jabori juggles a busy family and job and doesn’t have time to research and organise green home upgrades, but wouldn’t mind paying a bit more for heating if his bills were predictable. Jabori signs up for a home comfort contract, which involves paying for the type of comfort the customer wants rather than for units of electricity and gas. The provider commits to keeping Jabori’s home above 21°C in the morning and evening all year round for a fixed monthly price. As part of the contract, the provider conducts a survey of Jabori’s home and installs a heat pump, new radiators and loft and wall insulation. The provider also visits annually to service the equipment.

How could this help reduce emissions?

Home comfort contracts would shift the responsibility for reducing emissions from the householder to the provider. The provider would have an incentive to reduce their costs and would therefore work to reduce the energy required to heat the home. The most efficient option may be a heat pump, which would drive down emissions. Home comfort contracts would also reduce the burden on homeowners like Jabori to cover upfront costs and organise green home improvements, removing another barrier to uptake.

What are the limitations and what needs to change for this to happen?

Home comfort contracts may be unattractive to potential providers because, while the customer is paying a fixed amount, the cost of energy could fluctuate unpredictably. Providers with many customers could take significant losses or even go bust, causing widespread disruption to energy markets, as has been seen recently in the wake of energy suppliers collapsing. The fixed price also removes any incentive for householders to use less energy, making it even more difficult for providers to predict their costs.

Customers would need to agree to having a new heating system and insulation installed. These upgrades are difficult or impossible to remove and a large proportion of their cost comes from the work to install them. If a customer becomes unable to make payments, the provider would be unable to recoup their costs by removing the equipment they have installed. There are also questions about what happens if a customer sells their home and whether the new owner must agree to take up the contract.

How much progress has been made?

Energy Systems Catapult has explored home comfort contracts and heat as a service, conducting small trials with potential customers. Home comfort contracts are not currently available to the public.

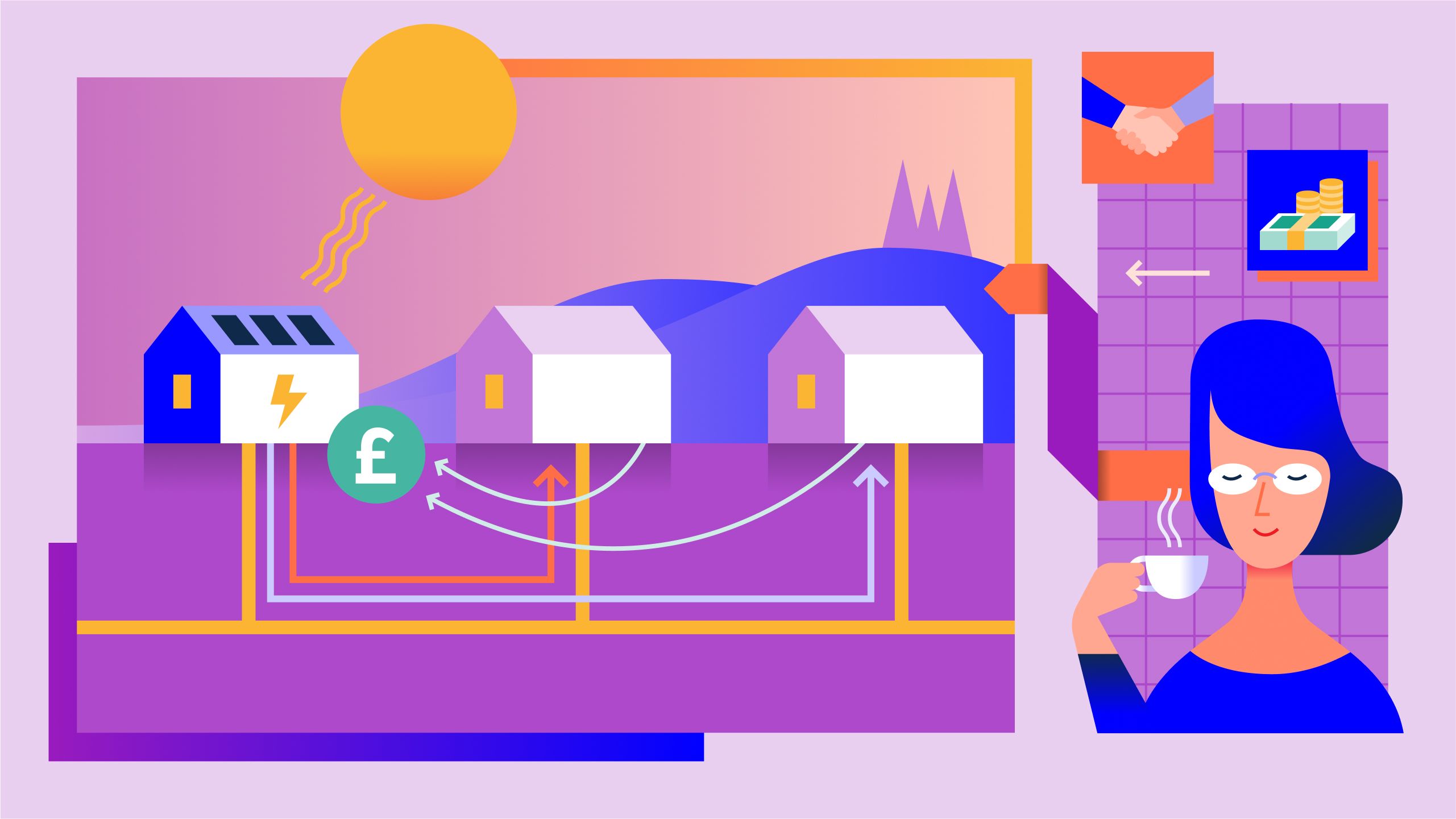

Local electricity trading

How might this work?

Elen is considering having solar panels and batteries installed in her home and wants to help her neighbours reduce their carbon emissions too. She finds out about local energy trading, which would allow her to sell excess electricity from her solar panels to her neighbours through their existing power supply.

Sharing electricity with neighbours and other buildings connected to the same local substation can reduce electricity network congestion and lower costs, meaning she can earn slightly more for each unit while her neighbours pay slightly less than they would on their usual tariff. This could help her offset some of the cost of the solar panels as well as help her neighbours decarbonise by using the energy she generates.

Seeing the potential benefits for herself, her community and her neighbours, Elen decides to spend more to have more solar and battery capacity installed.

How could this help reduce emissions?

Local electricity trading platforms could incentivise wealthier households to invest in excess solar and battery capacity to serve others in their area. This would help reduce carbon emissions by enabling people who live near those with excess generation to benefit from green and lower-cost electricity.

Widespread use could reduce the price of electricity for many households, lowering the running costs of renewable heating systems such as heat pumps and reducing demand for national grid capacity.

What are the limitations and what needs to change for this to happen?

It’s not clear whether the ability to sell electricity to neighbours would create an incentive to install excess generation and storage capacity in its own right, as potential customers would need to be fairly driven to take climate action.

Customers using their neighbours’ energy would likely need to be with the same energy supplier, and that supplier would need to agree to count the lower cost units within the user’s bills.

While those with wealthier neighbours could benefit from their excess electricity at discounted rates, people in areas with less solar generation capacity would not benefit. Overall, this could worsen energy inequality if not managed carefully.

How much progress has been made?

Energy Local has partnered with energy supplier Octopus to run Energy Local Clubs and conduct research into the potential benefits of local electricity trading.

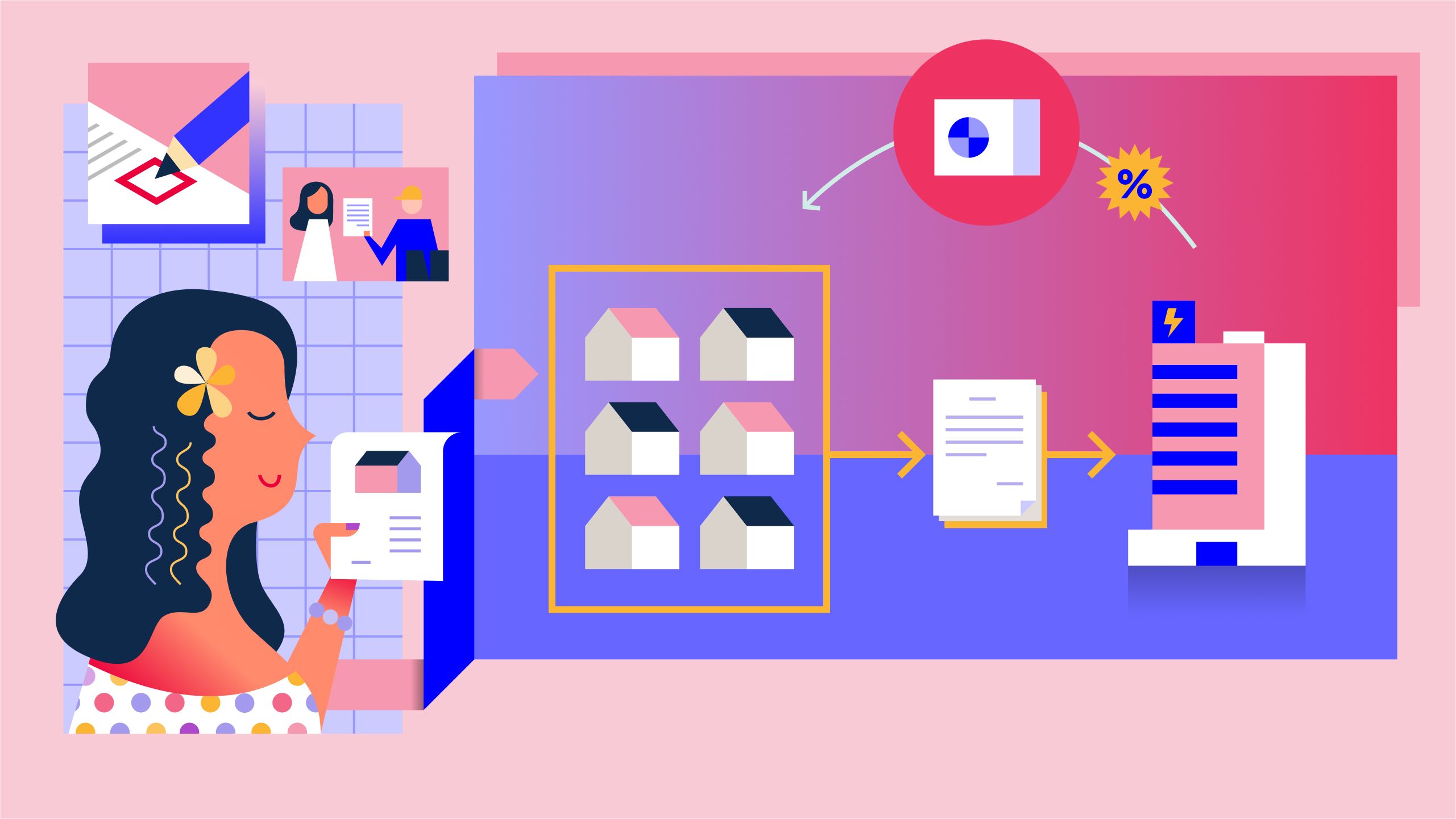

Group purchasing

How might this work?

Pele’s gas boiler is 15 years old and is likely near the end of its life. With the upcoming boiler ban, she’s been reading about heat pumps and is concerned about the costs of switching. She also has low trust in energy suppliers because of unpredictable energy prices. She receives a letter from her local council, inviting her to take part in a group purchasing scheme for green home improvements. She fills in a form to describe her home and needs and a retrofit coordinator visits her home to assess her property.

How could this help reduce emissions?

Making it cheaper and easier for homeowners to upgrade their heating system could accelerate decarbonisation and the approval of their local council could help to bolster trust in the technology. The lower costs are possible because heat pumps can be bought in bulk and installers can save money on marketing and by doing several installations in the same area at the same time.

What are the limitations and what needs to change for this to happen?

Heat pump installation can be complex, which might make it difficult to provide an accurate quote through an online survey. Local authorities will need to check if their local electricity grid has available capacity for a large number of heat pumps and whether there are enough installers with capacity in the area.

How much progress has been made?

iChoosr organises group purchasing of solar panel installations in partnership with local authorities and Nesta has explored how group purchasing could work for heat pumps.

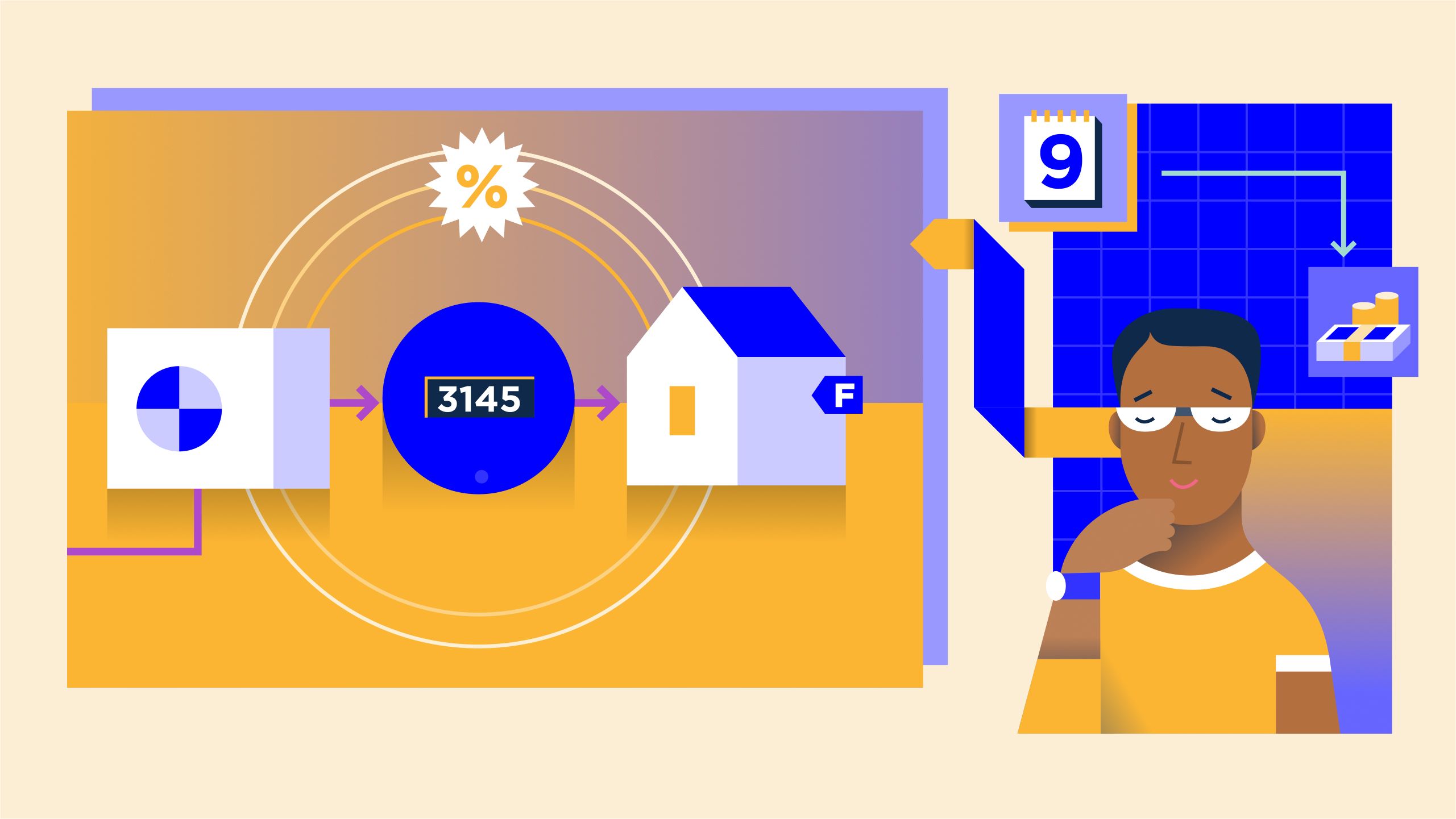

Discounted electricity for heat pumps

How might this work?

Aatish lives in a house with a poor environmental rating and is worried that a heat pump could use a lot of electricity to heat their home effectively. Their energy supplier offers them a heat pump with a performance guarantee, which gives a discounted electricity rate and caps the monthly cost of electricity used by the heat pump. This is possible because the heat pump has its own meter called a sub-meter, which keeps track of the electricity it uses.

How could this help reduce emissions?

Reducing the cost of electricity for heat pumps would incentivise takeup, reducing overall emissions. Measuring a heat pump’s electricity use separately also opens up a wide range of possibilities, including discounts for using electricity during periods of low demand.

What are the limitations and what needs to change for this to happen?

Energy suppliers would need to agree to count the different meters separately and deduct the usage from the household’s total usage amount to provide two separate pricing tariffs. Current energy regulation allows for more than one electricity tariff to be provided to a household, but they must be from the same provider.

If householders could choose a separate energy supplier for their heat pump, this could allow more flexibility. For example, a heat pump manufacturer could partner with an energy supplier to offer a performance guarantee, which any householder could sign up for, regardless of their existing supplier. Having two or more suppliers to one home would require changes to the supply framework, including the licence and industry codes.

How much progress has been made?

Research indicates that householders want to be able to choose multiple energy suppliers. Some heat pumps are currently installed with their own sub-meter, but this is currently limited to commercial applications and performance monitoring.

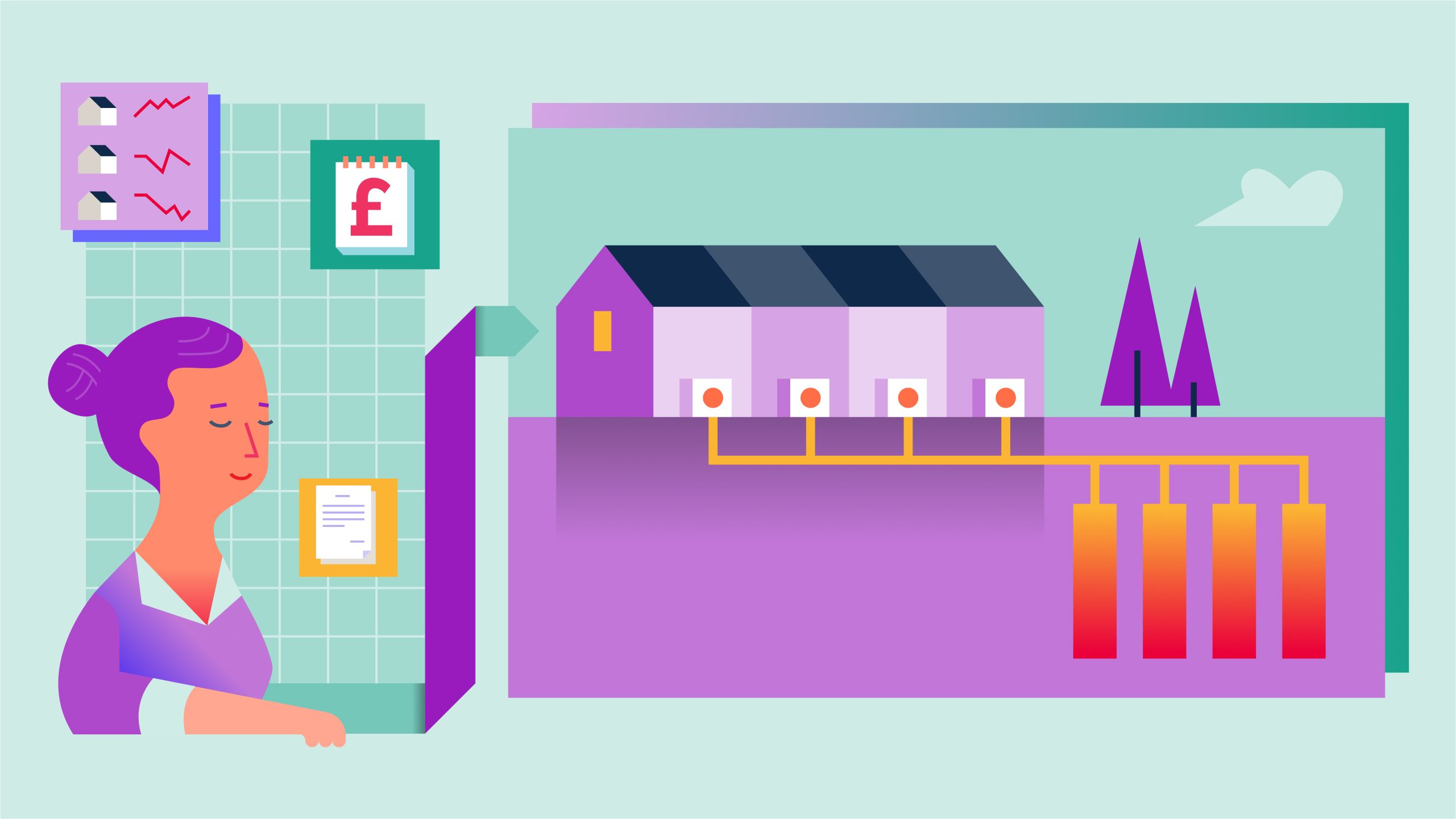

Street-by-street heat network

How might this work?

Bridget and her neighbours want to switch from gas boilers, but have little space for a heat pump outside their homes. Four households join together to sign up for a street-by-street heat network. The provider drills a series of boreholes near their homes, either in gardens or in the street. Piping is laid that each home can connect to, either at the time of installation or at a later date, just like the gas network. Bridget and her neighbours each have a small ground-source heat pump fitted, which is around the size of a small suitcase.

The heat pumps take heat from the ground network and each householder pays a fixed annual access charge, as well as for electricity to run the heat pump. After the initial investment to drill the boreholes, there is minimal cost to maintain them.

How could this help reduce emissions?

The heat pumps used in a street-by-street heat network are smaller than air-source models and can be installed indoors. This means that this approach could make it easier to switch for flats and terraced houses without enough outdoor space. Ground-source heat pumps are also more efficient, partly because their efficiency is not dependent on the outdoor air temperature.

What are the limitations and what needs to change for this to happen?

Private networks are not covered by current energy legislation, which could mean that access to redress may be limited.

Making this model work would require funding to drill the boreholes from investors that would be comfortable with very long timelines in the order of 40 or 50 years. This might limit the potential funders to government or very large finance companies.

Local authorities might need to agree to boreholes being drilled, as will owners of any land that piping crosses.

How much progress has been made?

Kensa Utilities has received £6.2 million of funding from the European Regional Development Fund to trial this model in Stithians, a village in Cornwall, to understand its potential. The trial is due to complete by March 2023.

What next?

These models have the potential to accelerate the decarbonisation of household heating in the UK. They could be particularly attractive to middle and higher income households that can afford some additional upfront cost. This is likely to contribute significantly to efficiency efforts because wealthier households are likely to have higher carbon emissions overall. The government can therefore accelerate decarbonisation by providing funding and changing legislation to support these and other innovative business models.

However, our research indicates that new business models will be inaccessible to many with lower incomes. These models also do nothing to incentivise landlords to upgrade their heating systems, since tenants usually pay energy bills. Alongside supporting these and other innovative business models, the government must intervene if the UK is going to reduce household carbon emissions at scale.

We have previously explored policy changes that could reduce the cost of heat pumps and even make them cheaper over their lifetime in comparison with gas boilers. These include shifting environmental levies from electricity to gas and removing VAT on home heating retrofits. We’d also like the government to explore more radical ideas such as progressive energy pricing, which could also contribute to redressing financial inequality.

It is clear that the government needs to take a stronger leadership role and set a coherent strategic policy direction including long-term funding to cover the cost of switching to low-carbon heating for low-income households. This would enable innovators, investors, consumers, energy companies and installers to better plan, make informed choices and focus their work.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of our interviewees for their insight and advice:

- Aidan Rhodes, Energy Futures Lab

- Amy Featherstone, Kensa Group

- Damien Kelly, Innovate UK

- Dhara Vyas, Energy UK

- Eva Oosterlaken, Royal College of Arts

- Finn Strivens, Royal College of Arts

- George Frost, iChoosr

- Joe McFadden, GenerationZero

- Jeff House, Baxi

- Justin Macmullan, Which?

- Karen Lawrence, Which?

- Kate Jones, Innovate UK

- Kevin Baillie, Ofgem

- Louise Vanheems, Nationwide Building Society

- Mareike Schmidt, Innovate UK

- Matt Lipson, Energy Systems Catapult

- Mike Fell, Centre for Research into Energy Demand

- Nicole Watson, UCL

- Dr Richard Hanna, Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London

- Sam Hampton, Energy Superhub Oxford

Thanks to Daniel Špaček for the illustration and Siobhan Chan for editing and designing this article.

This page is part of our policy library for decarbonising home heating.