Innovation Sweet Spots: Food innovation, obesity and food environments

Over the last decade, a surge of research and investment has given rise to a host of food innovations. Apps let us order from a myriad of different restaurants at the touch of a button and we're now growing meat in laboratories.

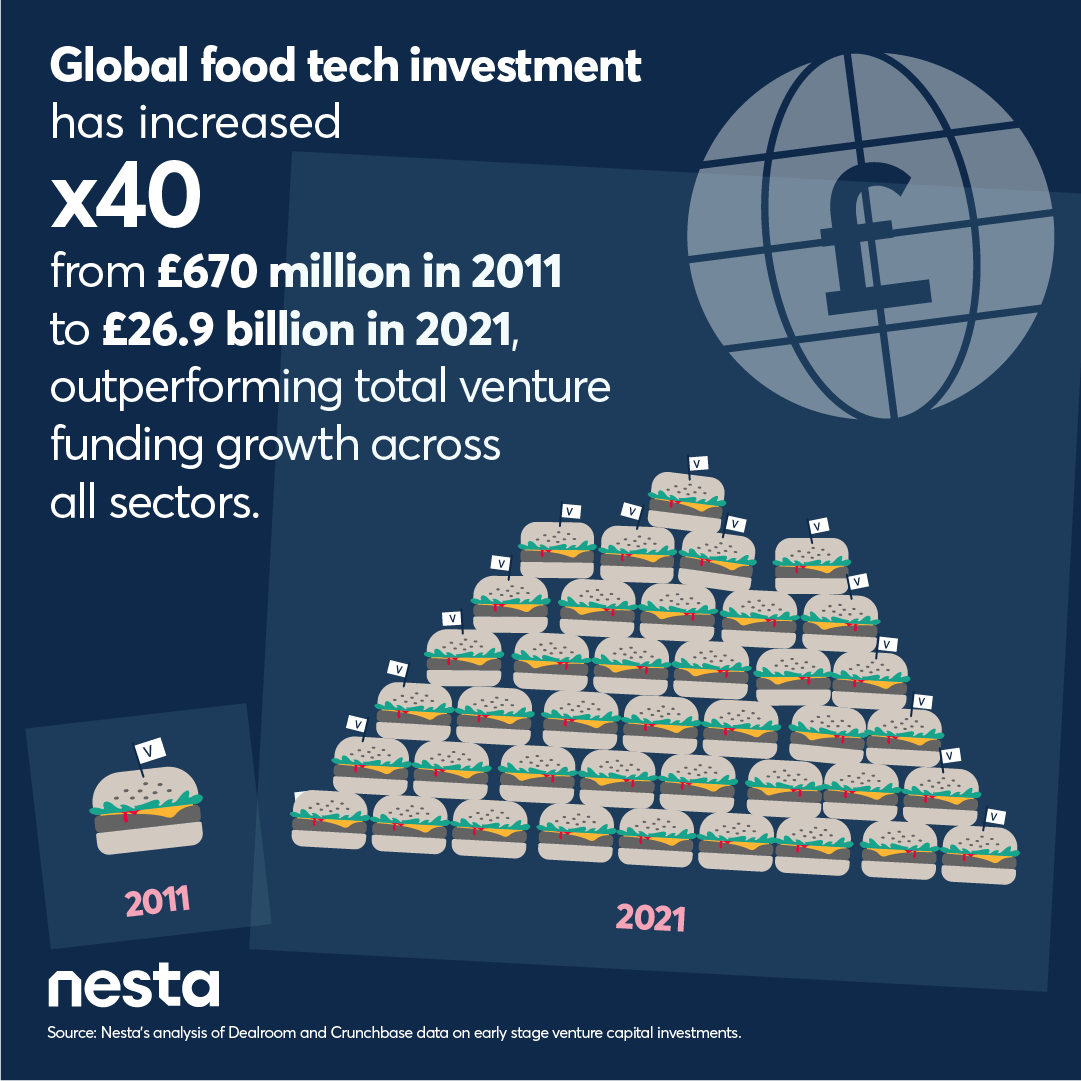

Our analysis shows that globally, venture capital investment into food tech has increased 40 times in the last ten years, reaching a new high of £26.9 billion in 2021.

But is the future of food headed in the right direction? The food industry’s focus to date has been on commercial success and sustainability – but should we be directing food innovation towards improving our health?

Food delivery attracted around 60% of venture capital investment in 2017-2021. The growth of delivery platforms, combined with the developments in ‘dark kitchens’ – cooking facilities that produce meals for delivery – and kitchen automation, pose a challenge to the quality of our food environments.

While these developments have not been focused on health to date, our research shows that we can improve food environments through innovation. New technology, processes and ideas must be directed towards providing more healthy food options if we are to reduce obesity and improve the nation’s health.

For example, patent applications and venture funding for reformulation have grown. Reformulation – where recipes or manufacturing processes are changed – can reduce calories and make people feel more full. It was deemed the innovation most likely to reduce obesity in the UK by our panel of food technology and food environment experts.

Our recommendations will encourage food innovation that is likely to be beneficial to health while mitigating the potential harms of technologies.

Giving food manufacturers tax relief and business rate reductions will incentivise and enable innovations that make food, and food environments, healthier. At the same time, funding must be made available for research that explores consumer concerns around such innovations.

The UK Government should support innovation to reduce obesity by partnering with private sector capital in relevant food tech companies. And we must explore the feasibility of a levy to help food companies aiming to improve health.

The UK has an opportunity to proactively harness food tech to make our food healthier - and it must act decisively.

What impact will the recent surge in food tech innovation have on food environments?

Where we live, work, shop and learn can influence the food we eat and how healthy we are. This is called the food environment: it could be your neighbourhood, workplace or even online spaces, and it includes everything you experience in those places that relates to food. Unfortunately, many of us live in environments where the food that is most readily available is unhealthy. Poor food environments are a major contributing factor to obesity in the UK, which has been steadily rising for three decades despite hundreds of policies being proposed (albeit not necessarily implemented) in order to tackle the issue.

In the last decade, we have seen an 'innovation boom' when it comes to the way food is produced, prepared, and distributed. With many new ideas now being tested in the market, our analysis shows that global venture capital investment into food technology and innovation start-ups increased about 40 times, from £670 million in 2011 to £26.9 billion in 2021.

More recently, in the five-year time period between 2017 and 2021, we estimated that venture funding for UK food tech start-ups has grown at a faster rate (108% growth) compared to, for example, the US, China or Germany.

However, this uncertainty is heightened by the fact that the market cycle of exuberant investment is coming to an end and venture funding for food tech start-ups in 2022 decreased by more than 50% compared to 2021.

Whilst the turbulence of the last year is undoubtedly significant, this report takes a longer view. We focus for the most part on the trends in the five-year period preceding the market downturn (ie, between 2017 and 2021), in order to consider the opportunities and challenges they pose to food environments. In this way, we have characterised the trends in investments made by investors and research funders in the previous market cycle, which will play out in the near future. Where relevant, we also discuss more recent shifts that occurred in 2022.

Searching for Innovation Sweet Spots

Nesta’s healthy life mission is committed to increasing the average number of healthy years lived in the UK and we aim to do this by reducing the incidence of obesity. Our focus is on improving food environments and making healthy eating easier, regardless of how little money or time people have, where they live or how health-conscious they are.

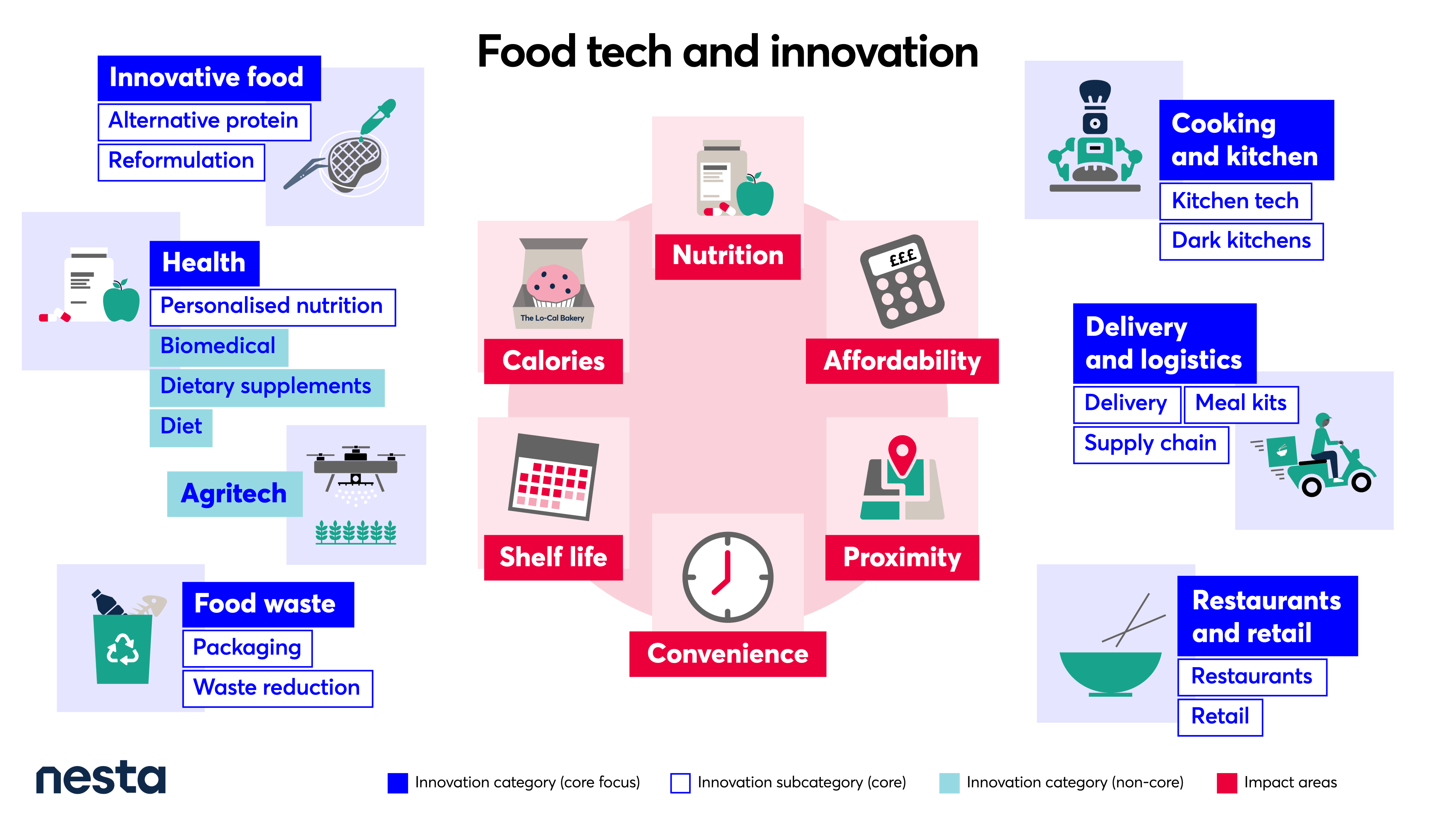

This application of Nesta’s Innovation Sweet Spots methodology aims to cut through the hype to better understand the trends in food technologies and innovations across different aspects of the innovation system, and considers the potential consequences of these trends. Given our focus is on the wider food environment we have used a broad definition of food tech, covering everything from the composition of food itself through to how it is prepared, accessed, and delivered. This broad definition is summarised in Figure 1, which clusters the categories of food tech encompassed in this report, and described in further detail in Chapter 1.

Main innovation categories and subcategories

We used the Innovation Sweet Spots methodology to analyse large datasets related to research activity, venture capital investment, and public discourse in the news and parliamentary debates – data that are commonly only considered in isolation. We analysed trends in these datasets (detailed in Chapters 2 to 5) and brought them together to build a multi-dimensional picture of the food innovation ecosystem.

Alongside this quantitative analysis, we also carried out qualitative 'sensemaking' exercises using strategic foresight techniques that involved a broad range of food industry stakeholders including investors, scientists, industry experts, and policymakers. We convened an expert panel to help us explore some possible consequences of these innovations, and then to rank them in terms of their potential impact on obesity (detailed in Chapter 6). Figure 2 provides an overview of the Innovation Sweet Spots approach.

Key findings

An investment boom in food delivery and logistics: A challenge for the quality of food environments?

Our analysis shows that investment in rapid food delivery technology, takeaway delivery app platforms and fifteen minute grocery delivery platforms has contributed the majority of recent venture capital food tech investment. Companies in the delivery and logistics innovation area, predominantly deliveries of takeaway meals and groceries, have attracted 60% of the global early stage food tech investment in the period from 2017 to 2021 (£11.2 billion per year on average).

We also found that the UK research funders are turning their attention to this area of innovation, and have supported, for example, projects on reducing costs of takeaway deliveries and enabling small businesses to share delivery drivers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Our analysis of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) data shows a 200% increase in funding between 2017 and 2021 for projects linked to food deliveries (when baseline total research funding has increased by only 11%). For the same time period, we also found a growing news discourse with a 350% growth of mentions in Guardian articles, which we use as a proxy for news coverage.

Parallel with the growth of takeaway delivery apps, we have also identified a steep rise of investment into 'dark kitchens' – preparation facilities which produce meals solely for takeaway delivery and not for restaurants. We estimated the investment into start-ups specialising in this area to have risen more than 140 times between 2017 and 2021, with about £485 million raised every year on average. The adoption of dark kitchens has been driven by the need to reduce costs, as takeaway food ordered via delivery apps presently costs a premium and companies in this sector still find it challenging to turn a profit.

Additional cost savings and productivity gains could be made in the future by introducing more automation and robotics in kitchens. Our analysis shows that the global venture funding for these types of kitchen technologies has also grown by about 81% between 2017 and 2021. For example, the kitchen robot Beastro, developed by Tel-Aviv based Kitchen Robotics, is specifically aimed at dark kitchens: the company claims that it can cut labour costs by more than 50%. Artificial intelligence-powered software providers such as the UK-based Winnow also enable kitchens to reduce food waste and run more efficiently. Ultimately, the confluence of these technologies may further drive the growth and adoption of rapid food delivery platforms in the coming years.

Given this growth, it is concerning that takeaway and grocery delivery app platforms were identified by our expert panel as the most likely technologies to increase obesity in the UK. There is evidence, for example, that out-of-home meals, which includes takeaways, are 21% more calorie dense than those cooked at home, and exposure to takeaways is associated with higher obesity prevalence. Furthermore, the higher density of takeaways in areas of greater deprivation suggests that increased consumption of fast food may contribute to deepening health inequalities.

Therefore, it is vitally important to ensure future innovation in this field is redirected towards improving the food environment alongside developing mechanisms to mitigate potential harms. In Chapter 7, we present policy recommendations designed to incentivise more private sector innovation in developing healthier options.

The rise of innovation in reformulation: Good news for the future of our health?

Reformulating foods to decrease energy (calorie) density or increase satiety – the feeling of fullness when consumed – can be achieved through several mechanisms. These include altering the proportions of different ingredients, adding novel ingredients developed by researchers or changing the process by which the food is prepared.

Our analysis of reformulation-related patent applications identified encouraging signals of active innovation around various types of reformulation. For example, we uncovered an approximately 165% growth across the past decade in applications for patents that reduce the calorie content of food by adding indigestible substances such as dietary fibre, which also has a range of health benefits.

Even more notably, we estimated that innovation in food patents that increase satiety has grown by about 580%. This significantly outperforms the global trend of approximately 70% growth in patent applications between 2010 and 2020.

Complementing this patent innovation, our venture capital investment analysis also found encouraging signals regarding the flow of investment into start-ups using food science to create new ingredients and reformulated products for healthier food. These start-ups range from those specialising in artificial sweeteners or products enhanced with dietary fibre to software platforms enabling various types of food reformulation. Investment in the area has increased almost 25 times between 2017 and 2021. Yet our estimates of the overall yearly investment amounts – £70 million – are small in comparison to most other types of food innovation, indicating that this is still an emergent trend in venture funding.

In contrast, we found that UK public research funding for reformulation has stagnated in the same time period, showing a decrease of 33%. Therefore, it is encouraging news that, as of late 2022, UKRI announced £15 million in additional funding for new diet and health research and Innovate UK announced a £20 million funding competition, some of which might also provide renewed support for reformulation along with consumer choice, physiology and biofortification.

The practice of reformulation was identified by our expert panel as the most likely food innovation category to reduce obesity in the UK compared to the suite of other innovations we analysed. An increase in public sector funding to accompany the relatively small (but rapidly growing) venture capital investment in reformulation could thus represent a very encouraging boost to the field.

This positive view of the potential for reformulation is also supported by recent research into the impact of the UK’s 2018 Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL), showing that manufacturers have reduced sugar levels of soft drinks without damaging sales, something which the policy was designed to achieve. Nesta’s recent analysis of in-home food and drink purchases has identified a set of food categories, in addition to soft drinks, that are most promising targets for reformulation to maximise impact on calorie consumption.

Research with our expert panel, however, highlighted the issue that, whilst reformulation to reduce calories in soft drinks is relatively easy (as the sugar can be replaced by a lower calorie sweetener and water), reformulating in other food categories and scenarios can be far more challenging. Barriers include: the need for a large degree of capital investment in research and production equipment; issues relating to consumer acceptance of both reformulated and entirely novel products; and the cost of multiple expensive new ingredients. These barriers can make reformulating to reduce calories difficult and expensive, especially for smaller businesses and challenger brands, who may lack the R&D resources of large corporates.

Consequently, in Chapter 7 we outline recommendations for incentivising food manufacturers and providers to invest in reformulation to produce healthier food. We also propose a mechanism for supporting promising small companies to get access to investment to support their continued R&D.

Personalised nutrition and meal kits: Access and uptake could limit potential health gains

Personalised nutrition services provide diet advice that’s tailored to an individual’s characteristics, such as lifestyle, genetics, gut microbiota, and metabolism. While evidence for the effectiveness of such personalised advice is still emerging, the number of nutrition app users in the UK, through which this advice is often communicated, has already increased more than fourfold since 2017, with a reported five million users in 2021. In the same time period, our analysis finds an impressive 552% growth in global funding for start-ups working in this area, reaching almost £500 million in 2021, and an emerging presence in the news discourse.

Meal kits contain pre-selected ingredients and recipes for customers to prepare home-cooked meals, thus freeing up time from meal planning and shopping. In the UK, there have been an estimated 5.7 million recipe box deliveries in 2022, up from 4 million in 2017. Our analysis shows that the global venture funding for such businesses (such as Germany’s HelloFresh or UK-based Gousto) has stabilised in the previous five years, at around £265 million per year.

In our expert ranking, personalised nutrition and meal kits emerged as having a potentially high chance of reducing obesity in the UK, if made accessible at scale, relative to the other technology interventions considered. Both meal kits and personalised nutrition services have the potential to promote healthy eating and help consumers engage and learn more about the food they eat and therefore make healthier choices.

This potential for widespread impact remains untested, however, as both types of services come at a price premium that many will find unaffordable, especially in light of the cost-of-living crisis. In the case of personalised nutrition, not only is a monthly subscription required, but a high degree of self-motivation needs to be sustained on the part of the user, to log their meals and keep following the nutrition advice. New business models that bundle these services with, for example, grocery deliveries or wellness or health insurance offers, might lower the cost barrier leading to wider adoption and impact.

Ultimately, however, these innovations do not tackle the underlying issues of an obesogenic food environment. Indeed, uneven access to such services may lead to further health inequalities between those who can afford to benefit from personalised nutrition or meal kits, and those who cannot.

Alternative proteins: An area of rapid growth but with unclear implications for health

Alternative proteins, which are being developed to replace traditional animal proteins, split into three major groups: plant-based proteins; proteins produced using microorganism fermentation; and lab-grown meat, in which animal cells are grown in laboratory and industrial conditions.

Our analysis has found multiple very strong signals around alternative proteins: they have attracted large and growing venture funding (£1.54 billion per year, with a 800% growth rate between 2017 and 2021) alongside being increasingly frequently mentioned in Guardian news coverage.

We also find that this area of innovation is attracting increasing amounts of UK public research funding – £1.7 million per year, representing a 175% growth between 2017 and 2021. This trend stands in contrast to the baseline, as total research funding has increased by only 11%.

The growth in venture and research funding has been driven by considerations around sustainability, food security, animal welfare and health concerns related to animal meat consumption. Nonetheless, this is still a nascent area, with indications that the early enthusiasm of consumers might have peaked and that there will be lower growth and more consolidation in 2023.

Moreover, the impact of alternative proteins on health is unclear. Plant-based burgers have been shown to have fewer calories, less saturated fat, and more fibre (though higher salt content) than their beef counterparts, suggesting that they have nutritional benefits. However, a report produced by the University of Cambridge has pointed out that many of the alternative protein products are extensively processed. High intake of ultra-processed foods have been associated with cardiovascular disease, and it may require 20 years of further studies before the health implications are fully understood. Plant-based protein meat alternatives are becoming increasingly available and are projected to reach price parity with animal protein in the next couple of years. If these products are to become an established part of people’s diets, as these factors suggest, it will be particularly important to understand the health impacts.

In the subsequent chapters, we also discuss trends in other technology areas, such as food waste – for example novel food packaging solutions and mobile apps to redistribute surplus food – as well as restaurant and retail innovations, like restaurant management software solutions. These innovation areas saw growth in venture and research funding in the five-year period between 2017 and 2021, and are undoubtedly important. However, they did not emerge in our evaluation as disruptive to the UK food environments, from a health perspective, compared to the technologies discussed above.

A multi-dimensional view of the food tech system

Through this research, we provide a view of multiple food innovation categories in parallel across multiple data sets. Reading across data sources in this way enables us to build a multi-dimensional picture of the technologies and innovations shaping our food environments.

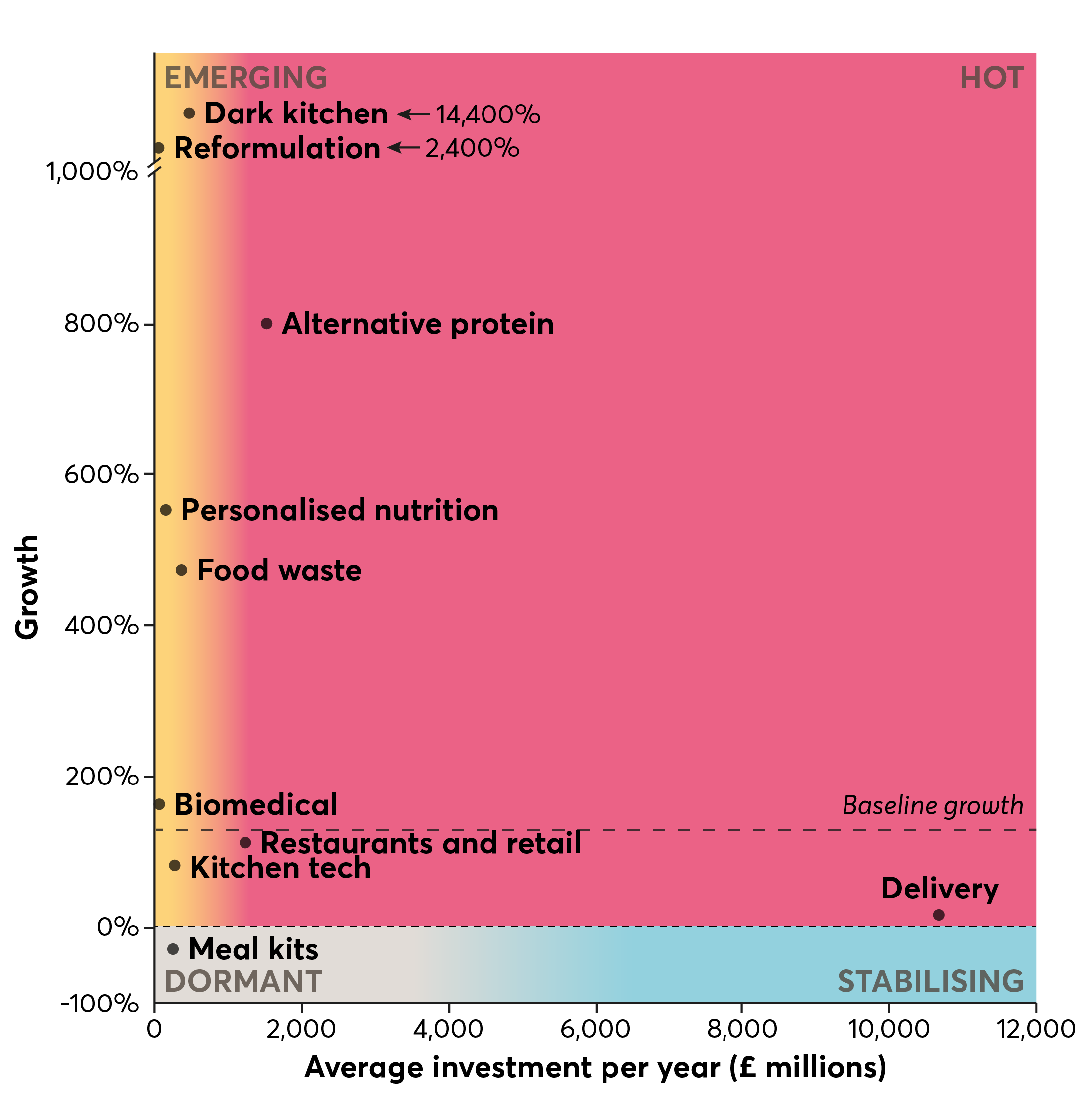

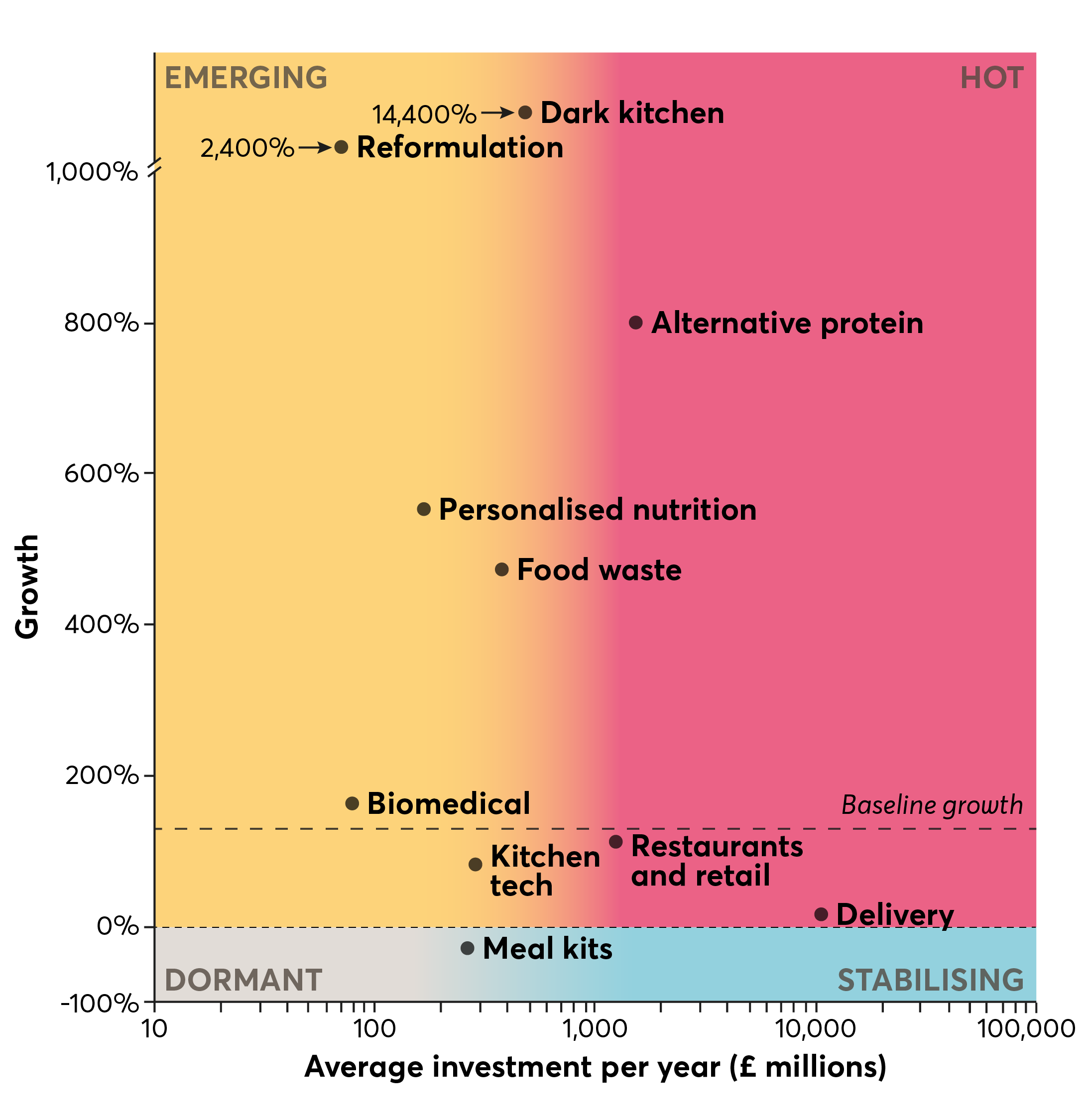

The chapters that follow provide a breakdown of the findings by dataset, and demonstrate how we have evaluated relative growth and magnitude across categories in a consistent way. As an illustrative example, Figure 3 summarises the trends in venture capital investment discussed in the section above, showing the magnitude and growth of investment as well as their place in our trends typology that categorises signals as ‘emerging’, ‘hot’, ‘stabilising’ or ‘dormant’. We categorised signals with a positive growth percentage as either ‘emerging’ (positive growth but relatively low magnitude) or ‘hot’ (positive growth and large magnitude). Conversely, signals with a negative growth percentage were deemed as ‘stabilising’ (negative growth but large magnitude) or ‘dormant’ (negative growth and small magnitude).

Early stage investment deals between 2017 and 2021 (eg, seed and series funding)

By considering various different innovation areas together, we could spot opportunities for ‘multiplier effects’, where one technology serves as an enabler for another: for example, growth in dark kitchens and kitchen automation technologies powering innovation in food deliveries.

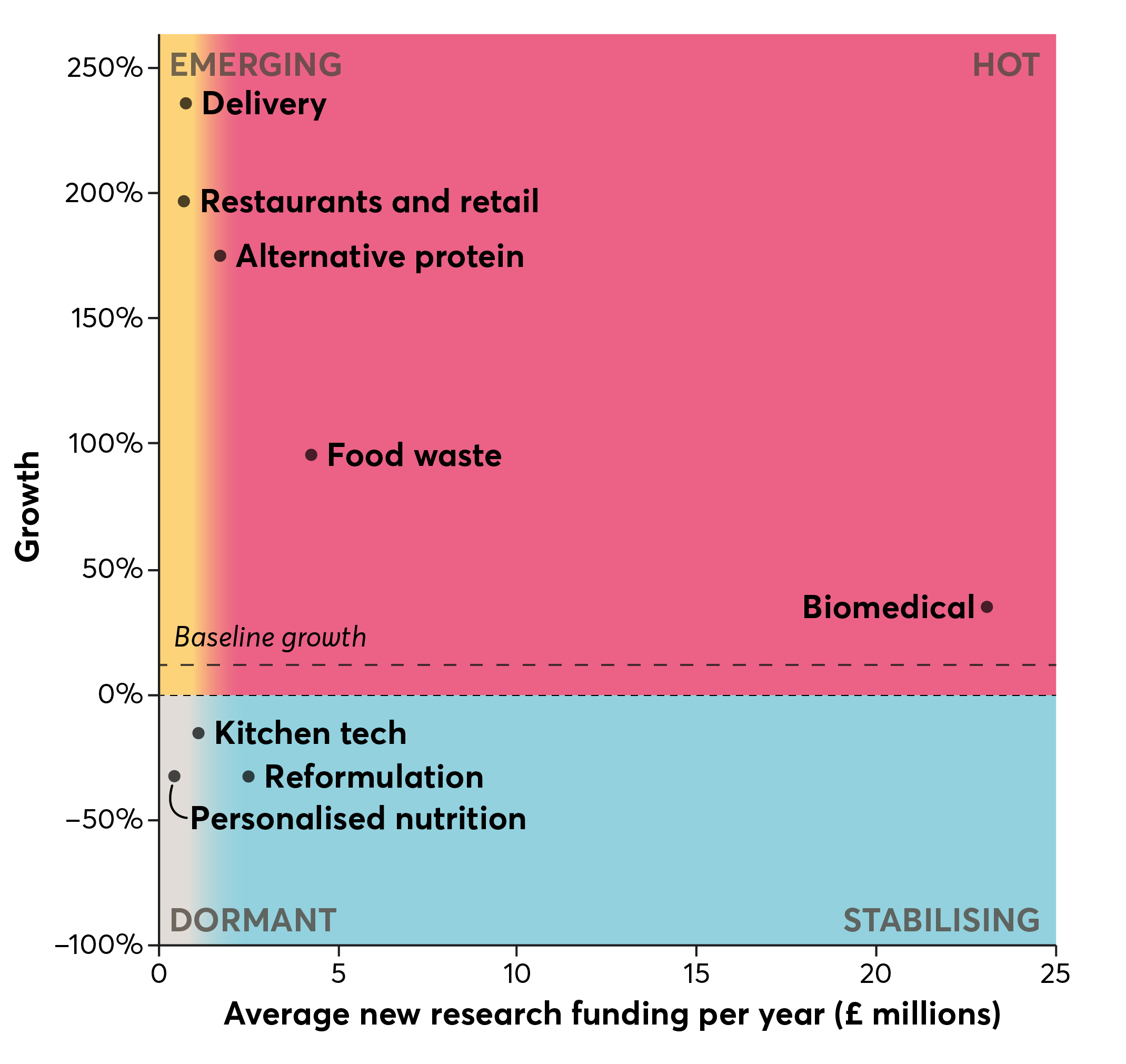

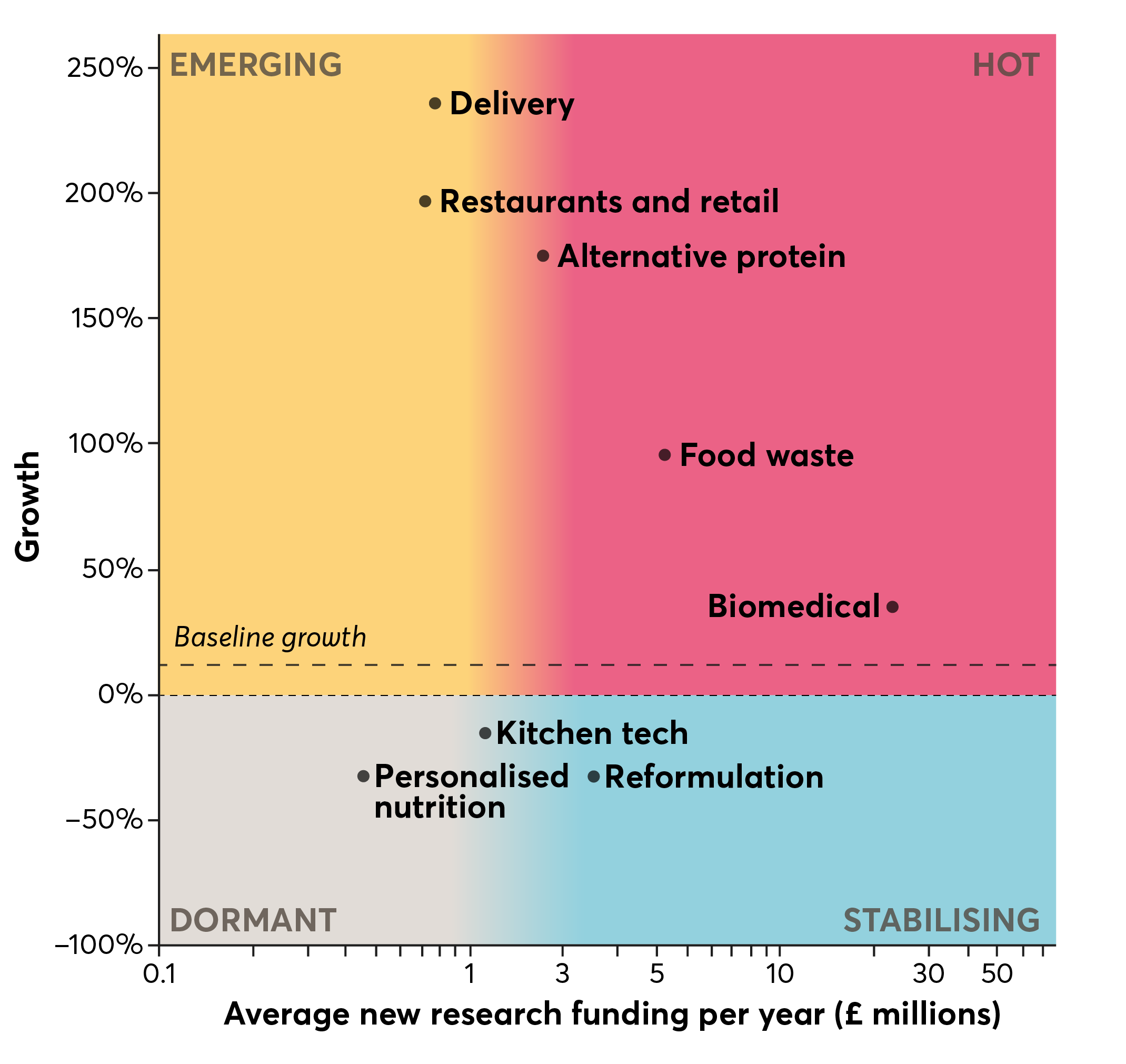

Combining multiple datasets also allows us to identify areas that are performing well across different indicators, such as alternative proteins, which in addition to being classed as ‘hot’ in venture capital investment also exhibit strong signals in the research funding dataset (see Figure 4 below). The research funding analysis also highlighted the large proportion of funding (66%) being directed to health-related research, which includes projects linked to biomedical research on obesity and metabolism as well as diets and weight management. This distribution suggests that research funding is tipped towards technologies or interventions aimed at individuals, such as medical interventions or diets, rather than innovations likely to shape the wider food environment as a whole.

Research project funding awarded by UKRI and NIHR between 2017 and 2021

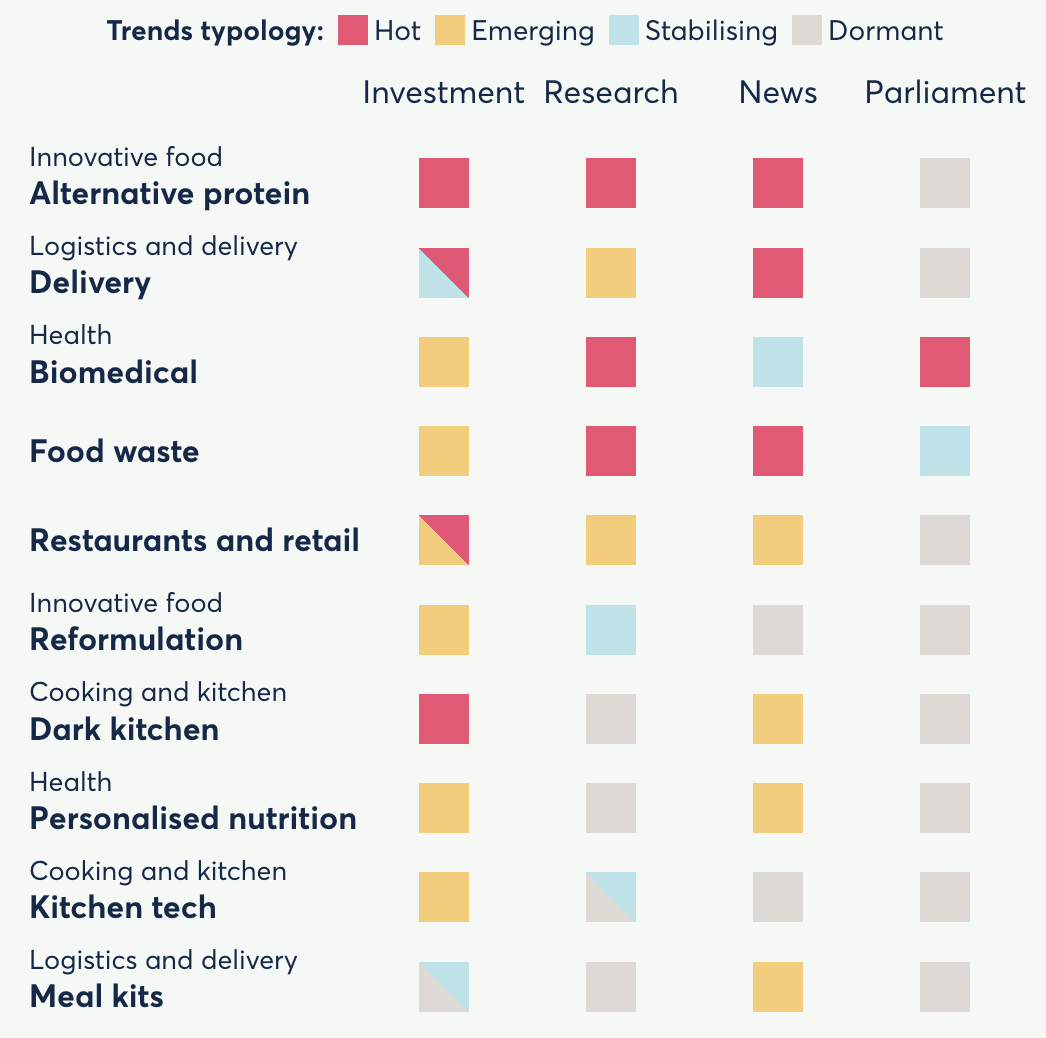

We have summarised our analysis across datasets in an experimental heat map (see Figure 5 below). Whilst being data informed, it offers a qualitative perspective on the trends across categories of food tech innovation and different types of indicators. Bringing together the analysis, we can see, for example, the contrast between strong growth in global venture capital investment across most of the examined technologies compared to a more uneven pattern in UK research funding – such as dark kitchens or personalised nutrition being classed as ‘dormant’ with respect to signals on research funding. The heat map also highlights that emerging food technologies do not yet appear to be a major subject of parliamentary debate (as measured using Hansard data), whilst there is growing media interest (as tracked in Guardian news).

Global venture capital investment, UK research funding, the Guardian news, and UK parliament discourse between 2017 and 2021

Looking ahead: Can we leverage innovation to create health benefits?

It has been an eventful decade for food tech, with substantial growth in venture capital and research investment, alongside an increasing degree of prominence in the news discourse. Growing investment, paired with ‘enabling’ technologies such as high speed internet and rapid low cost DNA sequencing, have given rise to innovations such as food delivery apps and personalised nutrition. However, as funding becomes more scarce in the near term due to tougher market conditions, many of these innovations may struggle to maintain traction in an economic downturn.

Looking ahead, the UK can do more to proactively harness the food innovations discussed in this report, with a view to making our food healthier, reducing costs and improving productivity of food services. Even technologies such as food delivery platforms that prompted concerns among our expert panel with regards to their impact on health and obesity could be improved further to promote healthier food choices.

We can do much to shape the trajectory of these nascent areas of innovation. Just as the UK Government has incentivised green energy technologies through legislation, subsidies and grants to tackle climate change, we should incentivise and support food manufacturers and providers across the food tech landscape to innovate towards applications and business models that actively improve our food environments. The recommendations that follow focus on steering innovation towards areas likely to be beneficial to health while mitigating the potential harms.

Recommendations

Based on our findings and advice from external experts, we have developed a set of recommendations around food tech innovation. These six recommendations build upon several made in a recent report published by Nesta that focussed specifically on food reformulation.

These included recommendations on: specific food categories that could be the most impactful targets for reformulation; industry ensuring accessibility of lower-calorie options for all consumers; setting up calorie reduction targets and mandatory reporting of data relating to health and reformulation; and establishing a dedicated body to design and set the targets.

Here, we extend these recommendations to food innovations beyond reformulation, and introduce a further set of complementary proposals to help steer food tech towards creating healthier food environments.

We provide detailed rationale for these recommendations in Chapter 7 and summarise them below. They fall into two groups: Fiscal incentives and Consumers.

Fiscal incentives

Calorie reduction and return on investment

While some of the following measures do represent a cost to the UK taxpayer, there has been significant research indicating a very positive return on investment from measures which cut calories. Modelling by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) indicates that a population-wide decrease in the UK of just 20 kcal per day, equivalent to around 1% of the average recommended daily calorie intake, would result in the following benefits over a 25 year period: 10,500 fewer deaths, a £2.52bn reduction in health and social care costs, and £191m gained in increased economic output. The model also calculated a financial value associated with the reduced mortality and morbidity totalling £7.98bn, bringing total financial benefits of £10.7bn.

1. Corporate tax relief of retrofitting food production plants to reformulate products for health

Background: Our expert panel pointed out that innovation in production and preparation processes can reduce calories in food products (eg, the use of steaming instead of frying). Unfortunately, a significant proportion of the UK food manufacturing infrastructure is ageing and inflexible, making such process innovation difficult or impossible, while the cost of replacing or retrofitting new equipment can make it prohibitively expensive for manufacturers.

Recommendation: The UK Government should introduce new tax allowances and deductions which lower the cost of new food manufacturing and preparation equipment, if the manufacturer can demonstrate that the change in equipment has the potential to credibly reduce calories.

2. Tax credits and business rates reduction to incentivise and enable innovations that improve the healthiness of foods and food environments

There are two sub recommendations, 2A & 2B.

Background (2A): Reformulating products to be healthier was highlighted by experts as being highly promising for reducing obesity. However, reformulation can be expensive and risks alienating consumers who may not like altered products.

Recommendation (2A): R&D projects specifically developing lower calorie healthier products should be rewarded, as part of R&D tax credits, with a higher rate of relief by HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC). This would therefore incentivise companies to carry out more research into making products healthier.

Background (2B): Within areas with no or limited healthy food options, high obesity and poor health outcomes, the negative impact of this unhealthy food environment is further amplified by takeaway delivery apps which make unhealthy options even more accessible.

Recommendation (2B): Businesses producing predominantly healthy meals should be given an 80% business rate relief, as is provided to charities, should they locate low-income areas with no or limited healthy food options and high obesity. This would enable takeaway delivery platforms serving the area to promote and provide healthier meals to the local population.

3. Explore the feasibility of a Health Innovation Levy whereby large organisations contribute funds into a central pot managed by the Government that could be drawn down by all companies innovating for health and obesity in the food industry

Background: Innovating to create healthier options can be expensive, difficult, and risky, so companies need to be encouraged to make this investment. It is particularly challenging for some small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) who lack the substantial R&D budgets available to larger corporates.

Recommendation: To further boost innovation for healthier food and food environments, large food retailers and manufacturers should make a contribution to a central fund. The level of contribution could be based upon sales derived from food categories identified as unhealthy or categories which have a high potential to be reformulated (as identified by Nesta’s recent analysis of in-home food and drink purchases). This government-managed fund would be used by companies to subsidise innovation that makes food healthier. SMEs would not have to pay the levy, but would be able to access funding from it.

4. The UK Government, potentially through the British Business Bank (BBB), should support innovation to reduce obesity by co-investing with private sector capital in innovative food tech companies whose products or services will have a positive impact on obesity

Background: Certain areas of food tech hold promise for reducing obesity but are not necessarily attractive to investors, so may struggle to get the funding they need to develop and scale.

Recommendation: BBB, a development bank owned by the UK Government, should co-invest with the private sector in food tech firms working on promising, but R&D intensive, intellectual property that can be credibly shown to create or improve access to healthy foods. The BBB already operates an existing fund, Future Fund: Breakthrough, which co-invests in R&D intensive companies within cleantech and life sciences.

Consumers

5. Funding for research and experimentation on addressing consumer concerns and issues to purchase reformulated products or other healthy food tech innovations

Background: Our expert panel highlighted reformulation as the innovation most likely to have a positive impact on obesity. Analysis also highlighted encouraging growth around reformulation related innovation. While external research indicates that people think positively about innovation in reformulation, this theoretical acceptance of products does not always translate to actual purchasing choices. While we know that some of this is due to barriers around cost, quality and taste, there are still gaps in our understanding of how to convert this positive attitude towards healthier reformulated products into actual behaviours.

Given their novelty, consumers might also have issues around other new technologies in the food tech space, like precision fermentation to produce proteins or robotics, which add another level of complexity that would benefit from further investigation.

Recommendation: UKRI or NIHR should provide dedicated funding for behavioural research and experimentation, potentially including participatory futures public engagement, to understand barriers and enablers for customer acceptability of reformulated products and other healthy food tech innovations. It could also support food producers and retailers in research and experimentation on consumer acceptance. The work could help create a virtuous circle by increasing customer demand for healthy reformulated products which encourages further development by industry.

To this end, we recommend that UKRI and NIHR apportion at least £1.25 million in additional, sustained yearly research funding across the next five years (ie, £6.25 million in total). The primary focus for this additional funding should be on addressing consumer concerns and issues of reformulated products.

The specific additional yearly amount of £1.25 million would correspond to around 50% of our estimated average yearly funding awarded to research projects linked to reformulation in 2017-2021. Additional support for the food reformulation innovation category is particularly pertinent when considering that our analysis shows new project funding linked specifically to reformulation has decreased by around 33% in 2017-2021.

We provide more detail on the implementation of these five recommendations in Chapter 7.

If you are interested in discussing our research and recommendations, please get in touch.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people for their valuable insights and advice that have informed this work. Please note that their input does not necessarily imply endorsement of the findings or recommendations.

- Steve Brewer (University of Lincoln)

- Valia Christidou (The Food Launchpad)

- Sue Feuerhelm

- Nadeen Haidar (Nesta)

- Dr Saher Hasnain (Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford)

- Professor Alexandra Johnstone (University of Aberdeen)

- Sid Kalita (Food Standards Agency)

- Alan Marson (New-Food Innovation)

- Professor Roger Maull (University of Exeter)

- Kathryn Miller (Innovate UK)

- Dr Milena von und zur Muhlen

- Nika Pajda (Bite Back 2030)

- Katharine Shipley (Food and Drink Consultant: Food Curious Food)

- Victoria Stewart (Food journalist)

- Suraj Thakrar (Turnells of London)

- Matt White (Frontier IP and Nandi Proteins)

- Dr Monika Zurek (University of Oxford)

We’re grateful to Celia Hannon for her support and leadership for the Innovation Sweet Spots project.

We thank our colleagues for their help and guidance on data analysis: Jack Rasala (Chapter 2); Adeola Otubusen (Chapter 4); Joshua Twaites (Chapter 5); Izzy Stewart and Elena Mariani (Chapter 7); Cath Sleeman, Lauren Orso, Luca Bonavita and Sebastian Ferreyra Pons (data visualisation); Jack Vines (data engineering).

We are also grateful to our colleagues who reviewed the report and provided their helpful advice: Celia Hannon, Lauren Bowes Byatt, Hugo Harper, Anna Keleher, John Loder, George Richardson, Matt Seden, Ravi Gurumurthy and Alexandra Burns.

Carrying out the data analysis for this report would not have been possible without the availability of high-quality, open-source code libraries of the Python scientific computing ecosystem. We thank the maintainers, contributors and supporters of this ecosystem. We also greatly appreciate the commitment to open-access data by the maintainers of the Gateway to Research portal (UKRI), Open Data site of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), Hansard dataset (TheyWorkForYou project and Evan Odell) and The Guardian Open Platform.

We thank DIAS Creative for the illustrations; Ella White, Eleanor Dowding, Angelica Bomford, Grace Fothergill and Mark Byrne from the Communications team for their work on this report; Emily Reynolds for copy-editing, and Siobhan Chan for editing and designing this report.

PatSnap was used for patent searches.

Important information

This report is not an investment recommendation or financial promotion, and should not be relied upon as such; it is an experimental analysis of venture capital investment, research funding, patent and public discourse data, focused on companies and research projects aligned to Nesta’s healthy life mission. The companies named within this report are cited purely as examples, helping demonstrate the analysis approach. Their inclusion should not be interpreted as an endorsement or indication of investment-worthiness by Nesta.