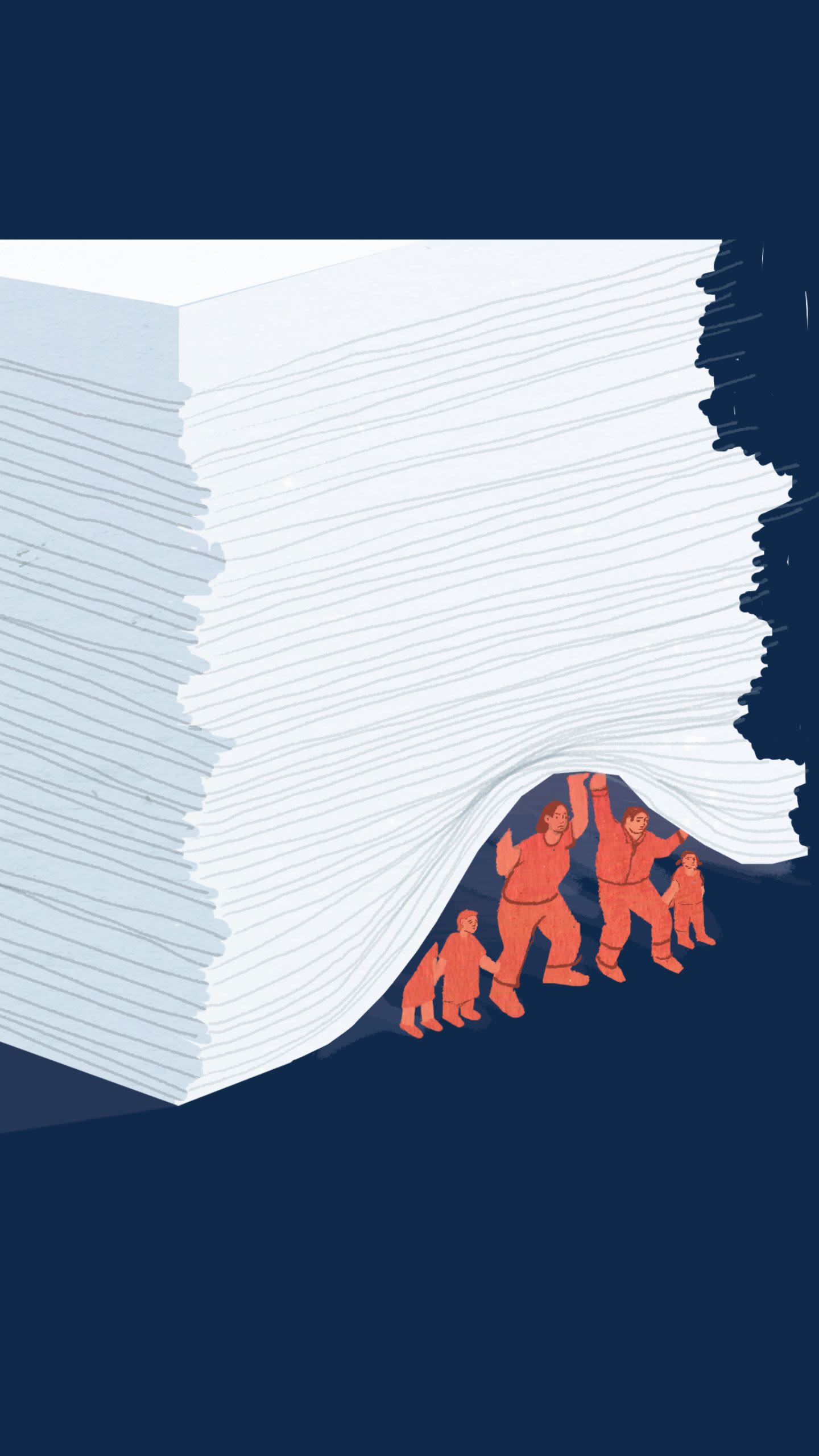

How might the two-child limit policy be affecting children’s early learning?

A summary of qualitative research conducted by Nesta with families impacted by the two-child limit policy

In 2017, the UK implemented the two-child limit (2CL) policy. Under this policy, families are no longer eligible for additional Universal Credit or Tax Credit allowances for their third and subsequent children if they were born after 6 April 2017. This policy impacts a significant number of households across the UK, resulting in a noteworthy reduction in family income.

As of April 2023, approximately 1.5 million children live in households affected by the 2CL, leading to an estimated annual financial loss of up to £3,235 per child for affected families. This is expected to rise to £3,455 per child in 2024-2025.

At Nesta, we have been exploring the impact of family income on child development outcomes. Research suggests that lower family income can contribute to poorer early childhood development. Two theories have been proposed to explain this relationship. First, the investment model suggests that parents with a higher family income can invest more money in goods and services that benefit their children’s development. Second, the family stress model suggests that parents living on lower incomes are more likely to be affected by stress, poor mental health and relationship conflict, which can have a negative impact on the parent-child interactions that are crucial for healthy child development.

Given what we know about the relationship between family income and child development, we conducted qualitative research to better understand the experiences of families affected by the 2CL policy, which lowers family income. Our research builds on evidence about the financial context of families affected by the two-child limit, and focuses specifically on families’ experiences of parenting and accessing early learning opportunities. Here we provide a summary of our research. Our complete findings and methodology can be found in our research report.

This research was conducted by Nesta as part of a mixed methods study we are working on in collaboration with the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS). In the second part of this study, the IFS analysed quantitative datasets to examine the impact of the 2CL policy on children’s school readiness. These findings were published by the IFS in 2025.

Our method

We sought to understand families’ experiences by interviewing 35 parents impacted by the 2CL living across four local authorities in England (Bristol, Newham, Birmingham and County Durham). In semi-structured interviews we asked parents about:

- how the 2CL policy had affected them

- any differences they observed between the experiences of their younger children who were affected by the policy versus their older children

- their youngest children’s experiences before starting school, including their access to early education and childcare.

- what difference would be made to their lives if they were to have access to additional financial support via the reversal of the 2CL policy.

Our sample was ethnically diverse, with an equal number of dual and lone parent families represented. Most parents we spoke to worked part time, and all families had three to five children.

Pseudonyms are used in this report to protect anonymity.

Our key findings

1. Families are experiencing severe and worsening financial hardship

The implementation of the 2CL coincided with families already facing significant financial pressures, including reductions in public assistance and availability of local services, as well as the cost of living crisis. Parents in our sample thought that the 2CL policy had further negatively impacted their family's financial situation compared to both their previous circumstances and those of similar families unaffected by the policy. Ultimately, many parents we spoke to were struggling to afford basic necessities for their family, which had led to some parents getting into debt just to cover their monthly living expenses. Parents accrued different types of debt when “borrowing to survive”, including arrears from rent and utilities, credit card debt and overdraft debt. Additionally, in some cases, parents chose to neglect their own needs, even skipping meals, to ensure their children’s needs could be met under their financial constraints.

“There’s not any money to cover everything. Finding money to cover food bills, everything. That’s the only issue I have, is keeping this roof over my head, keeping the council tax paid, just keeping the bills down, which is difficult.”

Tiffany, mother of three with one child impacted by the 2CL

“The majority of the time I'm in debt, because I'm unable to afford what they need. And sometimes I do it because they're my kids. I want them to have a childhood, you know?”

Nadia, mother of three with one child impacted by the 2CL

“It [the 2CL policy] has had a big impact on our family. They haven't been able to access things that maybe they would've if we had got that extra help. Even down to their diet, like to have fresh fruit and vegetables every day, to give them their five a day, it's very expensive. Our shopping bills had to be cut down. They just haven't had as many experiences that I would've liked them to have. It's kind of like we've gone into poverty now.”

Beth, mother of five with one child impacted by the 2CL

Our key findings

2. Children in affected households are losing out on opportunities to learn and play

The financial constraints of families affected by the 2CL meant their children were missing out on various types of enriching early life experiences. The parents we spoke to felt that their younger children, who do not receive the child element of universal credit, had less access to such opportunities compared with their older siblings at the same age.

More specifically, in comparison with their older siblings who had grown up in less impoverished circumstances, younger children affected by the 2CL policy were said to have had:

- less time in formal childcare

- less access to learning resources, such as toys, books and games

- fewer opportunities to take part in enriching activities, such as educational and fun trips or extracurricular activities

- fewer opportunities to socialise with peers.

“One thing I would say about my youngest is that she hasn't had the same opportunities about those kinds of things. So my eldest and middle child have always done things like dance and ballet and football, whereas my youngest has never done those things.”

Anna, mother of three with one child impacted by the 2CL

Time in formal childcare was the most highlighted early experience younger children were losing out on, followed by participation in extracurricular activities. Parents found childcare costs unaffordable, and often exclusively relied on their free childcare entitlements when seeking formal childcare for their youngest children. This was the case even for working families, who can claim back up to 85% of costs through Universal Credit (up to a maximum of £1,630.15 for two or more children). Some parents mentioned avoiding claiming costs through Universal Credit because they struggled to manage the shortage in funds, especially with the potentially lengthy reimbursement process. Relying on free childcare hours meant that families sometimes struggled to secure suitable or sufficient childcare. As a result, their younger children enrolled in nursery later or for fewer hours per week, when compared with their older siblings.

Lauren, a mother of three with one child affected by the 2CL, explained that she and her partner had decided to change their childcare arrangements for their youngest child due to lack of affordability:

“with my middle child I had been to nursery for four days a week, but now with my youngest child it’s only two [days], and then my mum has him for two [days].”

Ultimately, it was not only disappointing for children affected by the 2CL that they couldn’t access the same level of resources and experiences as their older siblings, but parents also saw this as a lost opportunity for their younger children to have fun, learn crucial life skills and meet developmental milestones.

Maira, a mother of four with two children impacted by the 2CL, spoke about how she already observed differences in her older and younger children’s socioemotional development, and attributed this to her younger children’s limited access to certain learning opportunities:

"My older two children were able to get more access to clubs and stuff like that so they are a bit more extroverted [...] with the younger two you can see that they're more – how can I explain it – they're more introverted as in like they're just more kept to themselves a bit more in that sense. Because they do not get the extra support on the things they want to do or play with they are just more lacking in skills from my sense of what I could do as a child.”

Many parents saw the 2CL as directly related to missed opportunities for their younger children.

For instance, Zainab, a mother of three with one child affected by the 2CL, explained that the absence of additional financial support for her youngest child limited their access to commonplace enriching early experiences:

"Because we haven't got that extra little bit of income, even simple things like going on days out, we're definitely doing that a lot less than we did with the first [child], even the second.”

In short, for families in our sample, younger children affected by the 2CL are experiencing an early childhood that lacks the same enrichment as their older siblings, and parents thought the 2CL had played a role in this.

However, it is important to note that parents also described their older children as being negatively affected by their limited family finances, given that there were generally insufficient resources available to meet all their children’s needs. Their older children’s wellbeing and socioemotional development was a particular concern for parents, as they were less able to afford to have their children take part in typical social activities, such as birthday parties or class trips, and thought they were at risk of being stigmatised by their classmates.

“It [the 2CL] does affect the children. I do think it affects them mentally. They’re definitely not the same as maybe their peers, as with parents, like, their confidence as well, like, I would definitely say my son might not want to go to town with his friends because he would need to ask me for money to get there or to spend when he’s down there.”

Solai, mother of four with one child impacted by the 2CL

“Because what happens is you get invited [to a birthday party] and you have to take a gift, isn't it, you can't go empty handed, you have to buy clothes for yourself, your child, it's like no, you can’t do this… [...] Because my older son..he obviously wants to go out, he wants to go to the friend’s party, he wants to go to birthday parties, he wants to join in with them…I have to explain to him that you can't because we don’t have that kind of money. It's a hard decision to make when you want to see your child happy.”

Naisha, mother of five with two children impacted by the 2CL

Our key findings

3. Parents are struggling to provide for their family and be the parent they want to be, which affects their own mental health

The parents we interviewed showed immense ingenuity and tenacity in increasing their families’ financial resources and giving their children the support they needed to grow and develop. They described their endless efforts in coping with severe financial pressures, such as planning months in advance to buy essentials like school uniforms, finding and creating free activities for their children, selling their belongings and even, in some cases, skipping meals.

However, parents felt demoralised that these efforts were not enough to compensate for the shortfall in their budgets, as they continued to struggle to afford basic living expenses, accumulated debts and their children missed out on opportunities for enrichment.

We also learned that while many parents would like to improve their financial position by increasing their working hours, this was very hard to achieve due to challenges with accessing suitable and affordable childcare.

“Fair enough it’s our choice to have the children, don’t get me wrong there, but when they’re putting so many roadblocks in our way to get to work…it’s not long I’ve been out of work and I would love to go back but, financially, it’s not looking like it’s going to happen unless I get a job at home.”

Ruth, a mother of four with two children impacted by the 2CL

Ultimately, parents in our sample clearly articulated how the 2CL affected their parenting. They felt that the policy prevented them from being the parent they aspired to be – one who always provides for and supports their children and sets them on the path for success. This was because the 2CL created additional financial stress for parents, curbed their investment in children's early development, and diminished their agency in shaping their children’s lives for the better. Parents were not only concerned about their current ability to fulfil essential parenting roles but they also worried about the lasting impact that growing up in financial disadvantage could have on their children's future wellbeing and success.

For instance, Maheen, a mother of four with two children impacted by the 2CL, expressed the wish to be:

“genuinely invested in our kids, that they'll get a better life and maybe they could have more opportunities.” She voiced concerns that her children would become stuck in their current reality of financial hardship: “whereas now it's like they've got this scrimping saving kind of mentality [...] It'll affect them in the long run. They'll just end up in the same cycle as us.”

Through our discussions with parents, it was clear that the weight of managing immense financial hardship, and feeling unable to fulfil their parenting role as a provider, was contributing to parents’ lowered mental health and wellbeing. Parents frequently told us they felt increased stress and worry, while some also described feeling guilty that their younger children couldn’t experience the same opportunities as their older siblings. Additionally, some parents thought that their financial situation had exacerbated pre-existing mental health difficulties or had led to their onset.

Beth explained how hard it had been to cope with the 2CL as a lone parent raising five children in the aftermath of splitting up with her partner; this “put more pressure on because everything was on me then. There wasn't any other benefit. There was nothing else really to apply for [...]so I ended up going through depression. I'm still kind of battling it now.”

Evelyn, a mother of three with one child impacted, spoke about how mental health problems such as anxiety can make it even harder to handle financial pressures effectively:

“I suppose it impacts on you emotionally that you can’t always do what you wanna do for the child and it’s harder for me to juggle all the bills and everything else. You just have to really budget. I have anxiety as well, medical condition, so I’m not always good at budgeting and that makes it more difficult ‘cause you don’t get any extra money at all, you don’t get any extra help with housing or any part of it really. I get £13 a week for the third child and that’s it. So I have to use the other money for him really as well. So it does get you down.”

Our key findings

4. Parents view the 2CL policy as unfair, punishing and a hindrance to children’s early development

Across the interviews, we were struck by how strongly parents felt about the 2CL policy. Many articulated their wish for the 2CL to be modified or reversed, arguing that the policy is unfair and punishing to children.

Parents thought the 2CL policy was unfair because it felt arbitrary and unavoidable; few parents in our sample had chosen to have an additional child while already receiving Universal Credit and knowing they would be affected by the 2CL. Some did not know about the policy prior to pregnancy, some had unplanned or coerced pregnancies and others transitioned to Universal Credit after their third child was born, due to an unexpected change in financial circumstance. Ultimately, parents in our sample stressed the point that the policy denies support to parents who are doing the best they can to provide for their families, but whose children are suffering because their income is insufficient to meet their most basic needs.

For instance, Milie, a mother of three with one child impacted by the 2CL, acknowledged the motivations behind the policy (to reduce the public deficit) while emphasising that the Government’s decision to reduce public spending via the 2CL had been personally catastrophic for her family:

“My partner and I are both educated to postgrad level. We’ve both got, what on paper, are really good jobs. We’ve both worked hard to get them. Yet, we…our outgoings are more than our incoming each month. And there is nothing we can do about it. And it’s just because of spiralling costs in the country, obviously, but it’s a nightmare situation to be in.

“And I think maybe once upon a time, before I was a parent in this situation, I might have thought the two-child limit was fair enough, and in some ways it is, I understand there’s gotta be a cut off but our lives are really, really difficult at the moment, and that’s not the children’s fault. I don’t think it’s ours either.”

Additionally, parents characterised the policy as a hindrance to children’s good development as it reduced their ability to invest in their children’s early learning opportunities.

Maheen explained that if she were to receive the child element of Universal Credit for her third child (who was currently ineligible), this would make a big difference to all her children as:

“the extra money would be more for [the children’s’] development. It'd be like a little bit extra surplus instead of always trying to make ends meet.”

We asked parents in our sample what they would do if they were able to receive the child element of Universal Credit for all of their children (approximately £250 per child per month).

They said that they would use the additional money to better make ends meet and increase their family’s quality of life, as well as provide their children with learning opportunities they were currently missing out on.

Parents spoke about their desire to use additional financial support to:

- enrol their children in paid extracurricular activities and after school clubs, such as sports and music classes

- enrol their children in additional hours of formal childcare

- take trips to outdoor places in the UK

- take trips to educational or fun play-based spaces and attractions

- secure tutoring or additional support for their children in difficult subject areas

- buy educational toys or learning resources

- buy resources for educational activities at home

- buy resources to equip them for school, such as uniforms or shoes

- provide more opportunities for their children to socialise with friends and family.

Our takeaways

This study adds to previous research, such as the findings from the Larger Families study, by gaining deeper insights into how the financial pressures experienced by parents affected by the 2CL may be influencing their children’s early development before they start school. Existing theories suggest that family income can affect child development through two main pathways – higher income can enable greater investment in goods and services for the child's benefit (investment model) and lower parental stress, in turn allowing for better parent-child interactions (family stress model).

Our qualitative research with 2CL-affected parents indicates that their severe financial hardship may negatively affect their children's early development through both pathways. Parents shared how financial challenges limit their ability to invest in goods and services that could benefit their children, and they also reported experiencing stress, worry and poor mental health, potentially affecting their parenting role. Despite their resilience, many parents felt demoralised, guilty and exhausted due to financial pressures. Some of the parents we interviewed were very concerned that their current financial challenges could be shaping their young children’s lives in ways that could go on to limit their long-term life chances.

In the next part of our study, we continued to explore the impact of the learning about the early development of children affected by the 2CL, particularly with regards to how the 2CL may be impacting school readiness. The IFS carried out quantitative analysis of outcome data gathered in children’s reception year of school, to investigate whether there is evidence of a relationship between children being affected by the 2CL and poorer outcomes at age five.

The IFS quantitative analysis found that the introduction of the two-child limit has had no significant effect on the proportion of third and subsequent children in England achieving a good level of development (GLD) 1 at age five. This is the measure of ‘school readiness’ assessed at the end of reception year, and is the focus of the government’s ‘Opportunity Mission’ target.

This research only analysed impacts on GLD at age five, so these findings do not rule out other effects of the policy on children’s wellbeing and future life chances, or on their parents. Read the IFS report in full.