How does parenting impact children's development?

How does parenting impact children's development?

Decades of research show that early childhood development is critical for children’s future success. When children start school behind their peers, it often becomes harder for them to catch up - with long-term consequences for their education, health, and life chances.

We also know that a child’s development is shaped by the educational, financial and emotional environment they grow up in and that children experience inequalities in these environments from a very young age.

Among the many interrelated factors that influence early childhood development, parenting consistently emerges as one of the most significant.

A substantial body of research highlights that parenting plays a powerful role in supporting children’s early learning and development. It is the everyday interactions between parents and children - talking, playing, setting routines, offering comfort and guidance - that help shape how children grow, learn, and thrive. We also know that a wide range of interventions aimed at strengthening parent-child relationships and the home learning environment have proven to be effective. There are meaningful ways in which communities, professionals and governments can support parents and caregivers to enhance children’s developmental outcomes.

In this article we explore what ‘types’ of parenting are most effective for children’s development, and what forms of support are most helpful in enabling caregivers to be the best they can be.

What does effective parenting look like?

Parenting isn’t one-size-fits-all, but research shows that some approaches are more beneficial to children than others when it comes to supporting child development. Two major UK studies, the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) and the Study of Early Education and Development (SEED), shed light on the parenting styles that are most effective.

Children need warm, positive relationships with their parents

One of the most consistent findings in UK-based parenting research is the strong link between warm, positive parent-child relationships and better outcomes for children. But what does ‘warmth’ really mean? In this context, parental warmth includes both verbal expressions of affection and appreciation (like saying “I love you” or giving praise) and non-verbal gestures (like hugs) that communicate love, acceptance, support, and responsiveness to a child’s needs. This type of parenting is thought to help children thrive because it supports the development of secure attachment - an emotional bond that forms when children feel safe and consistently cared for. However, it is worth noting that what secure attachment looks like may vary across cultures.

Secure attachment offers key benefits, including:

- healthy relationships – children learn how to show empathy and prosocial behaviour by observing and internalising their caregivers’ actions

- the confidence to explore and learn about the world around them – a securely attached child sees the caregiver as a ‘secure base,’ making them more willing to explore, take risks, and seek help when needed.

In short, a warm parent-child relationship is foundational to both learning and social-emotional wellbeing in early childhood.

Findings from the MCS study reinforce this. Drawing on that data, research by IFS found that at age 3:

- children who experienced warmer and more affectionate relationships with their parents tended to show stronger cognitive development and fewer socio-emotional difficulties

- in contrast, higher levels of conflict in the parent-child relationship were associated with weaker cognitive outcomes and more behavioural and emotional challenges.

Later findings from the SEED study found similar results. A 2020 study found that at age five, children with warmer, more positive relationships with their parents tended to do better in several areas.

- These children often showed stronger verbal skills and scored higher on all areas of the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile (EYFSP), an early learning assessment.

- They also tended to have better social and emotional development - for instance, they were generally better able to manage their emotions and get along with others.

- On the other hand, children whose relationships with their parents involved more conflict often had lower communication and language scores at age five.

These findings highlight that warm, responsive parenting is not just emotionally nurturing but plays a critical role in shaping children’s early learning, behaviour, and overall development.

Children need warm, positive relationships with their parents

One of the most consistent findings in UK-based parenting research is the strong link between warm, positive parent-child relationships and better outcomes for children. But what does ‘warmth’ really mean? In this context, parental warmth includes both verbal expressions of affection and appreciation (like saying “I love you” or giving praise) and non-verbal gestures (like hugs) that communicate love, acceptance, support, and responsiveness to a child’s needs. This type of parenting is thought to help children thrive because it supports the development of secure attachment - an emotional bond that forms when children feel safe and consistently cared for. However, it is worth noting that what secure attachment looks like may vary across cultures.

Secure attachment offers key benefits, including:

- healthy relationships – children learn how to show empathy and prosocial behaviour by observing and internalising their caregivers’ actions

- the confidence to explore and learn about the world around them – a securely attached child sees the caregiver as a ‘secure base,’ making them more willing to explore, take risks, and seek help when needed.

In short, a warm parent-child relationship is foundational to both learning and social-emotional wellbeing in early childhood.

Findings from the MCS study reinforce this. Drawing on that data, research by IFS found that at age 3:

- children who experienced warmer and more affectionate relationships with their parents tended to show stronger cognitive development and fewer socio-emotional difficulties

- in contrast, higher levels of conflict in the parent-child relationship were associated with weaker cognitive outcomes and more behavioural and emotional challenges.

Later findings from the SEED study found similar results. A 2020 study found that at age five, children with warmer, more positive relationships with their parents tended to do better in several areas.

- These children often showed stronger verbal skills and scored higher on all areas of the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile (EYFSP), an early learning assessment.

- They also tended to have better social and emotional development - for instance, they were generally better able to manage their emotions and get along with others.

- On the other hand, children whose relationships with their parents involved more conflict often had lower communication and language scores at age five.

These findings highlight that warm, responsive parenting is not just emotionally nurturing but plays a critical role in shaping children’s early learning, behaviour, and overall development.

Children benefit from clear expectations and consistent routines

Being a responsive and warm parent does not mean an absence of expectations, rules or routines for children. Findings from UK-based research show that children can benefit from this as part of the parenting they experience.

For example, data from the MCS shows that children with consistent daily routines, namely regular bedtimes, tend to have better cognitive outcomes and fewer socioemotional difficulties at age three. Similarly, SEED researchers found that parents who set more limits generally tended to have children with stronger verbal and non-verbal communication skills at age five. Those children were also more likely to meet expected standards in reading, maths, and science at age seven.

These findings relate closely to the concept of parenting styles, a framework first published in the 1960s. Parenting styles are generally described along two dimensions: the degree of control or demand placed on children and the level of warmth or responsiveness shown to them.

Baumrind, author of the original paper on parenting styles, proposed three main categories:

- authoritative (or positive) parenting – high in demands and responsiveness

- authoritarian parenting – high in demands but low in responsiveness

- permissive parenting – low in demands and varying in responsiveness.

International research has shown that authoritative parenting, which combines clear expectations with emotional support, leads to more positive social and emotional outcomes for children. Some UK-based research has replicated the link between authoritative parenting and child development.

Meanwhile, the SEED study has not found any significant associations between authoritative parenting and child outcomes to date. However, researchers did find that permissive parenting was linked to poorer literacy and numeracy scores at age five, as well as weaker performance across all Key Stage 1 outcomes at age seven. Authoritarian parenting was also associated with lower verbal abilities during the first year of school. Together, findings from the MCS and SEED studies indicate that high warmth and high demands are both crucial for early child development, strongly supporting 'authoritative parenting' as the best choice.

Children benefit from clear expectations and consistent routines

Being a responsive and warm parent does not mean an absence of expectations, rules or routines for children. Findings from UK-based research show that children can benefit from this as part of the parenting they experience.

For example, data from the MCS shows that children with consistent daily routines, namely regular bedtimes, tend to have better cognitive outcomes and fewer socioemotional difficulties at age three. Similarly, SEED researchers found that parents who set more limits generally tended to have children with stronger verbal and non-verbal communication skills at age five. Those children were also more likely to meet expected standards in reading, maths, and science at age seven.

These findings relate closely to the concept of parenting styles, a framework first published in the 1960s. Parenting styles are generally described along two dimensions: the degree of control or demand placed on children and the level of warmth or responsiveness shown to them.

Baumrind, author of the original paper on parenting styles, proposed three main categories:

- authoritative (or positive) parenting – high in demands and responsiveness

- authoritarian parenting – high in demands but low in responsiveness

- permissive parenting – low in demands and varying in responsiveness.

International research has shown that authoritative parenting, which combines clear expectations with emotional support, leads to more positive social and emotional outcomes for children. Some UK-based research has replicated the link between authoritative parenting and child development.

Meanwhile, the SEED study has not found any significant associations between authoritative parenting and child outcomes to date. However, researchers did find that permissive parenting was linked to poorer literacy and numeracy scores at age five, as well as weaker performance across all Key Stage 1 outcomes at age seven. Authoritarian parenting was also associated with lower verbal abilities during the first year of school. Together, findings from the MCS and SEED studies indicate that high warmth and high demands are both crucial for early child development, strongly supporting 'authoritative parenting' as the best choice.

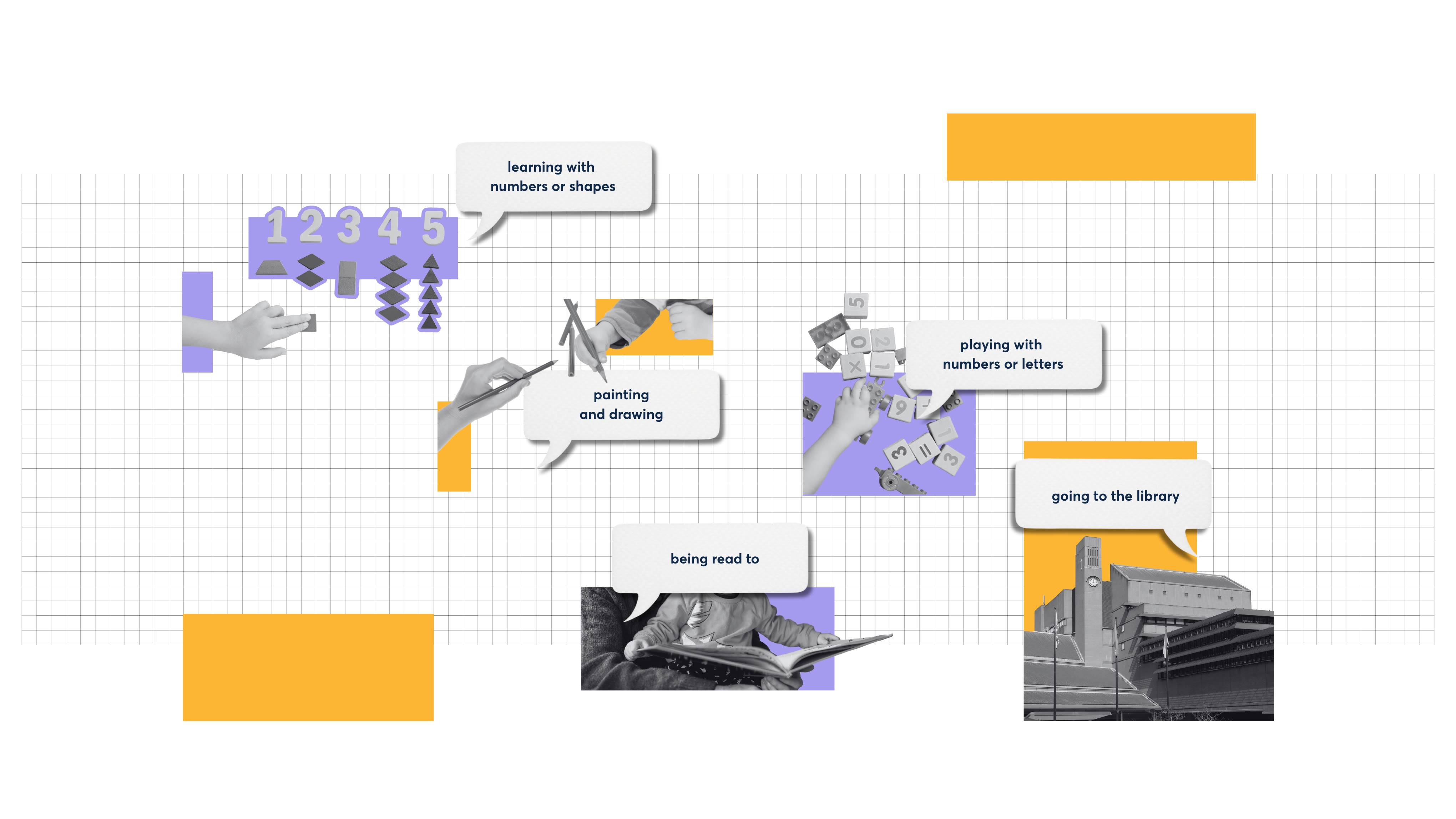

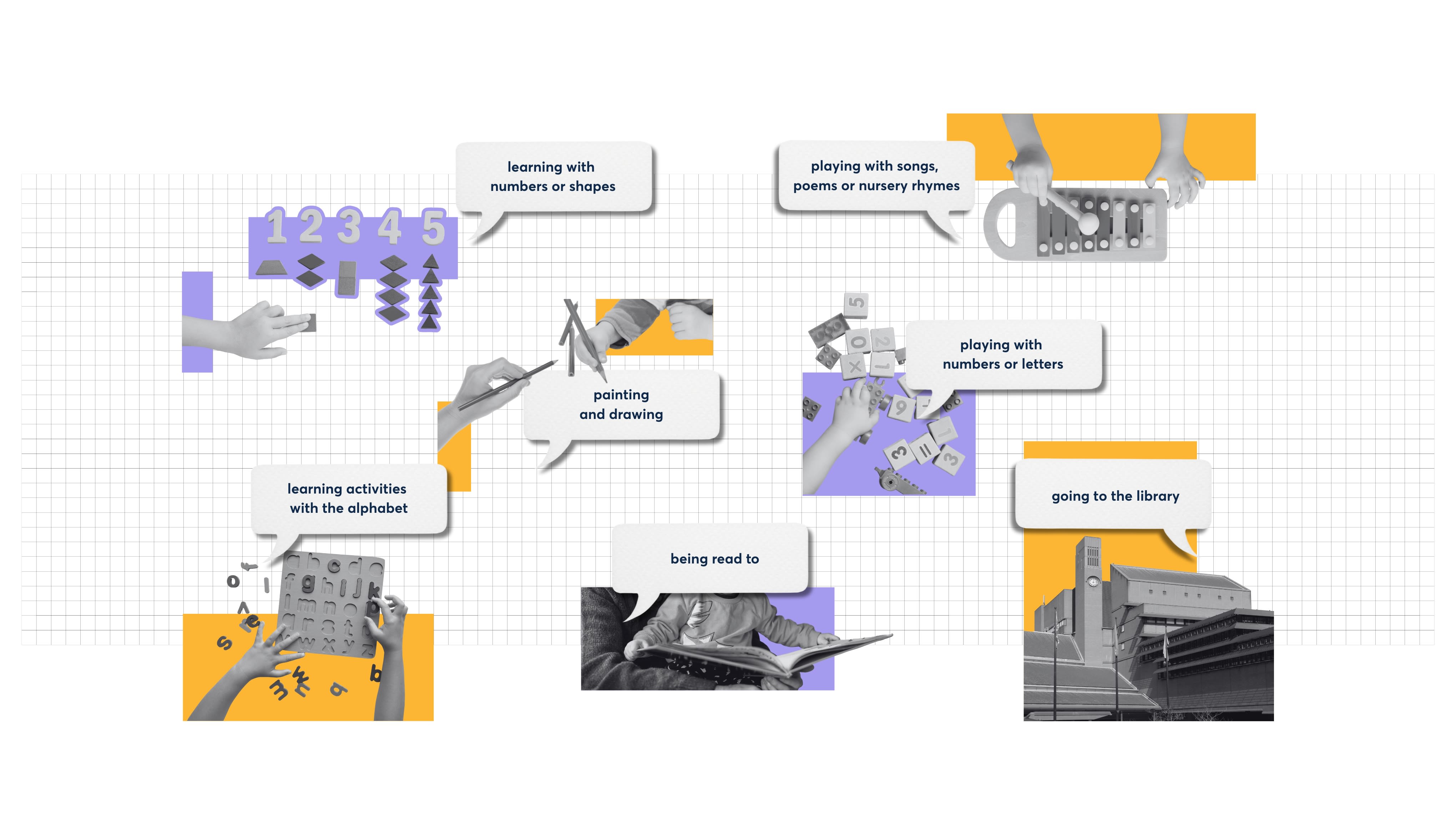

Children thrive in a stimulating home learning environment

A child’s home learning environment (HLE) refers to aspects of home life that support learning, including the frequency and quality of joint activities between caregivers and children. This includes things like talking and reading together, singing songs or playing educational games. It also includes access to materials that enable these activities, like books and toys. The graphic below shows an example of some of the activities that researchers identify to understand the quality of the home learning environment.

A stimulating home learning environment, characterised by regular, high-quality engagement in these activities, has been consistently linked with better developmental outcomes for children up to age 18. Importantly, these effects were independent of family income or parental education, suggesting that what parents do with their children matters, regardless of background.

More recent evidence from SEED reinforces these findings. At age five, children whose home environment had a higher score on measures of home learning were more likely to achieve higher scores across all areas of the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile and had better verbal abilities by the end of Year 1. These advantages were still evident at age seven: children from families with stronger early HLE scores tended to perform better in reading, writing, maths, and science at Key Stage 1, and score higher on composite measures and the national Phonics Screening Check.

Other research also points to the importance of home learning practices in the earliest years. Analysis by the IFS found that greater frequency of stimulating parent-child activities, such as reading, storytelling, or playing educational games, was associated with stronger early cognitive skills and fewer socio-emotional difficulties at age three. The evidence paints a consistent picture: effective parenting in the early years is characterised by a balance of warmth, structure, and stimulation.

Children are more likely to thrive when their caregivers are emotionally responsive, set clear expectations and routines, and actively support early learning through everyday activities like reading, talking, and playing.

While no single approach fits all families, the research underscores that how parents engage with their children day to day, through both relationships and routines, has meaningful links with early development, particularly in language, social-emotional skills, and school readiness.

Children thrive in a stimulating home learning environment

A child’s home learning environment (HLE) refers to aspects of home life that support learning, including the frequency and quality of joint activities between caregivers and children. This includes things like talking and reading together, singing songs or playing educational games. It also includes access to materials that enable these activities, like books and toys. The graphic below shows an example of some of the activities that researchers identify to understand the quality of the home learning environment.

A stimulating home learning environment, characterised by regular, high-quality engagement in these activities, has been consistently linked with better developmental outcomes for children up to age 18. Importantly, these effects were independent of family income or parental education, suggesting that what parents do with their children matters, regardless of background.

More recent evidence from SEED reinforces these findings. At age five, children whose home environment had a higher score on measures of home learning were more likely to achieve higher scores across all areas of the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile and had better verbal abilities by the end of Year 1. These advantages were still evident at age seven: children from families with stronger early HLE scores tended to perform better in reading, writing, maths, and science at Key Stage 1, and score higher on composite measures and the national Phonics Screening Check.

Other research also points to the importance of home learning practices in the earliest years. Analysis by the IFS found that greater frequency of stimulating parent-child activities, such as reading, storytelling, or playing educational games, was associated with stronger early cognitive skills and fewer socio-emotional difficulties at age three. The evidence paints a consistent picture: effective parenting in the early years is characterised by a balance of warmth, structure, and stimulation.

Children are more likely to thrive when their caregivers are emotionally responsive, set clear expectations and routines, and actively support early learning through everyday activities like reading, talking, and playing.

While no single approach fits all families, the research underscores that how parents engage with their children day to day, through both relationships and routines, has meaningful links with early development, particularly in language, social-emotional skills, and school readiness.

How can we best support parents to parent effectively?

If we know parenting is important, and the types of parenting styles and behaviours that are more likely to help children learn and develop, how do we ensure this is the parenting children actually receive?

The research findings we’ve discussed point to the need to support parents in a variety of ways to help them build strong relationships, maintain consistency and create enriching learning environments. For example, parents might need financial support to better invest in a home learning environment, or they might need flexible working hours to be able to have the time to be responsive to their children and set the right rules and routines for them.

Parents' need for multiple types of support to promote their children’s development might be best evidenced by the positive impact of Sure Start centres on children’s educational outcomes in England, as these centres used a model of support where multiple agencies, systems, and professionals worked together to meet families’ needs.

While there is no ‘silver bullet’ for supporting effective parenting, parenting programmes are one of the most impactful tools available. These programmes aim to improve child outcomes by increasing parents’ knowledge and confidence to use positive parenting behaviours in daily family life. Foundations’ review of 75 parenting programmes delivered in the UK, from conception to age five, found that about a quarter had strong evidence of improving child outcomes - including educational achievement, mental health, and behaviour.

So, what types of parenting programmes stand to help parents and their young children in the UK? Below we discuss three examples of effective parenting programmes during a child’s earliest years, drawing from Foundations’ analysis. Each of these interventions are different in how and where they support caregivers and which families they seek to support. However, all have been found to be effective in supporting children’s development and are implemented in the UK.

1) Family Nurse Partnership

Home visiting parenting programmes typically involve regular visits by health professionals to parents within their home setting, either during pregnancy or the first years of a child’s life. A prime example of an effective home visiting programme that has been implemented in the UK is the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP). FNP is an intensive home-visiting programme for disadvantaged or vulnerable first-time mothers, beginning in pregnancy and delivered long term through 64 structured 90-minute visits by specially trained nurses. Visits focus on maternal health and child development. Multiple rigorous evaluations show FNP has a positive, long-term impact on children: an England-based randomised control trial found that FNP mothers reported increased self-efficacy, while their children showed fewer developmental concerns and improved language, speech, and communication skills, compared to those not in the programme. A follow up study found that children whose caregiver received the FNP programme were more likely to achieve a good level of development at reception age, signifying school readiness.

1) Family Nurse Partnership

Home visiting parenting programmes typically involve regular visits by health professionals to parents within their home setting, either during pregnancy or the first years of a child’s life. A prime example of an effective home visiting programme that has been implemented in the UK is the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP). FNP is an intensive home-visiting programme for disadvantaged or vulnerable first-time mothers, beginning in pregnancy and delivered long term through 64 structured 90-minute visits by specially trained nurses. Visits focus on maternal health and child development. Multiple rigorous evaluations show FNP has a positive, long-term impact on children: an England-based randomised control trial found that FNP mothers reported increased self-efficacy, while their children showed fewer developmental concerns and improved language, speech, and communication skills, compared to those not in the programme. A follow up study found that children whose caregiver received the FNP programme were more likely to achieve a good level of development at reception age, signifying school readiness.

2) Incredible Years Preschool

Group-based parenting support typically involves bringing parents together regularly, where a facilitator (a professional or peer) helps parents build their knowledge and confidence around parenting. Incredible Years (IY) Preschool Basic is one such example of an effective early years parenting programme. More specifically, it is a group-based programme that supports parents of three to six year olds in managing their children’s challenging behaviour. It uses role-play, video modelling, and group discussions to encourage positive parenting strategies. UK-based studies have demonstrated its long-term effectiveness in reducing child behaviour problems and improving parent-child interactions.

2) Incredible Years Preschool

Group-based parenting support typically involves bringing parents together regularly, where a facilitator (a professional or peer) helps parents build their knowledge and confidence around parenting. Incredible Years (IY) Preschool Basic is one such example of an effective early years parenting programme. More specifically, it is a group-based programme that supports parents of three to six year olds in managing their children’s challenging behaviour. It uses role-play, video modelling, and group discussions to encourage positive parenting strategies. UK-based studies have demonstrated its long-term effectiveness in reducing child behaviour problems and improving parent-child interactions.

3) Triple P (Level 4)

Level 4 of the Triple P is designed for parents of children aged three to four who are experiencing behavioural difficulties. Delivered one-to-one over ten weekly sessions by a trained practitioner, the programme teaches practical strategies to promote positive behaviour and manage common challenges through age-appropriate, consistent discipline. Triple P has been implemented across the UK and is evidence-based. There is evidence of a short-term positive impact on children’s development from at least one rigorous study. One Australian-based study found that the programme led to increased parental competence and lowered behavioural problems in children.

3) Triple P (Level 4)

Level 4 of the Triple P is designed for parents of children aged three to four who are experiencing behavioural difficulties. Delivered one-to-one over ten weekly sessions by a trained practitioner, the programme teaches practical strategies to promote positive behaviour and manage common challenges through age-appropriate, consistent discipline. Triple P has been implemented across the UK and is evidence-based. There is evidence of a short-term positive impact on children’s development from at least one rigorous study. One Australian-based study found that the programme led to increased parental competence and lowered behavioural problems in children.

In summary, while parenting support is likely to be needed in many forms, parenting programmes are an important piece of the puzzle. Working to scale these programmes is a powerful way of increasing parents’ knowledge and confidence to support children’s development across the UK.

Conclusion

Overall, the evidence is clear: parenting plays a vital role in shaping children’s early development, and there are proven ways to support parents to give their children the best possible start in life. Warm, responsive relationships, consistent routines, and stimulating home learning environments are all within reach when caregivers have access to meaningful, practical help. In fact, Nesta’s recent market analysis of parenting support found that if evidence-based parenting programmes were scaled up, approximately 8,000 more children in the UK could reach a ‘good level of development’ at age five every year.

As inequalities in early development persist across the UK, supporting parenting through investment in evidence-based programmes must be central to any strategy that seeks to close the gap and improve life chances for all children. Our work seeks to improve children’s development outcomes through supporting the information environment that makes this possible. This includes testing new programmes, reviewing existing ones, and better understanding family needs - to ensure the most effective support can be scaled up to help families across the UK.