Innovation Sweet Spots: Food innovation, obesity and food environments

Chapter 4: UK food tech public research funding trends

In this chapter, we describe UK trends in public research funding for food technologies and obesity. We analysed research project funding awarded by the UKRI (the UK Research and Innovation body) and NIHR (The National Institute for Health and Care Research). UKRI is responsible for funding a large proportion of UK research and innovation (£6.14 billion, or about 40% of the UK Government’s R&D expenditure in 2020), while NIHR has a total budget of about £1.2 billion. Importantly, research funding trends have the advantage of being an even earlier signal compared to venture funding or patents, as project abstracts describe research plans for several years ahead and feature more exploratory or academic research.

We identified a wide range of research projects related to food innovations and obesity research, amounting to about £272 million in total awarded funding between 2017 and 2021. The majority (66%) of this funding has been awarded to health-related projects linked to obesity, including research on diets, weight management, and metabolism. The funding for such projects has increased by approximately 43% in the five year period, which significantly outperforms the total research funding growth estimated at around 11%. Hence, according to our trends typology, research funding for the ‘health’ category appears ‘hot’ (ie, high growth and large funding). This contrasts with the more ‘emerging’ trend (ie, high growth but lower level of funding) in health-related venture capital investment discussed in Chapter 2.

Funding for projects that cover food innovations and technologies impacting the wider food environment appears to have increased at an even faster pace (71% growth between 2017 and 2021). Delivery and logistics and food waste innovation categories appear to be ‘hot’, whereas projects related to restaurants and alternative proteins appear ‘emerging’. Conversely, the research categories of ‘food reformulation’ and ‘cooking and kitchen’ appear closer to ‘stabilising’ and ‘dormant’ respectively, with small or even negative growth (which, interestingly, contrasts the patent trends in reformulation discussed in Chapter 3).

Overview of research funding for food innovations and obesity

In the following section, we provide an overview of the research funding trends across the main innovation categories. This is followed by a more detailed discussion about trends in each category with examples of recent research projects.

We estimate that between 2017 and 2021, there has been about £272 million in total funding to new projects related to food innovations and obesity research. The majority of this funding (66%) has been awarded to health-related projects, which includes research linked to obesity, diets, weight management, and metabolism (see ‘health’ category in the Figure 32 below). This is followed by research related to ‘delivery and logistics’, ‘innovative food’ and ‘food waste’.

This distribution of funding suggests a greater research focus on innovation that targets individuals, such as medical interventions or diets, rather than innovations that might impact the wider food environment, such as food deliveries, kitchen technologies, or reformulated foods.

Funding for research into food tech and obesity outperforming baseline funding growth

When comparing the growth of different research categories, we find that the dominant category of health-related projects has grown by an estimated 43% between 2017 and 2021, receiving about £36.3 million per year of new funding. This likely reflects the prominence of obesity in the UK public health policy agenda, with 13 strategies containing more than 600 wide-ranging policies published by the UK government since 1999. In late 2022, the government announced a further £20 million in research funding to develop new medicines and digital tools to tackle obesity.

Interestingly, funding for research linked to the wider food environment, such as food deliveries or restaurants and retail, has grown at an even faster pace (71% growth between 2017 and 2021). Both growth rates compare favourably to the baseline increase of the total combined UKRI and NIHR research funding, which we estimate to be at around 11% in the same time period.

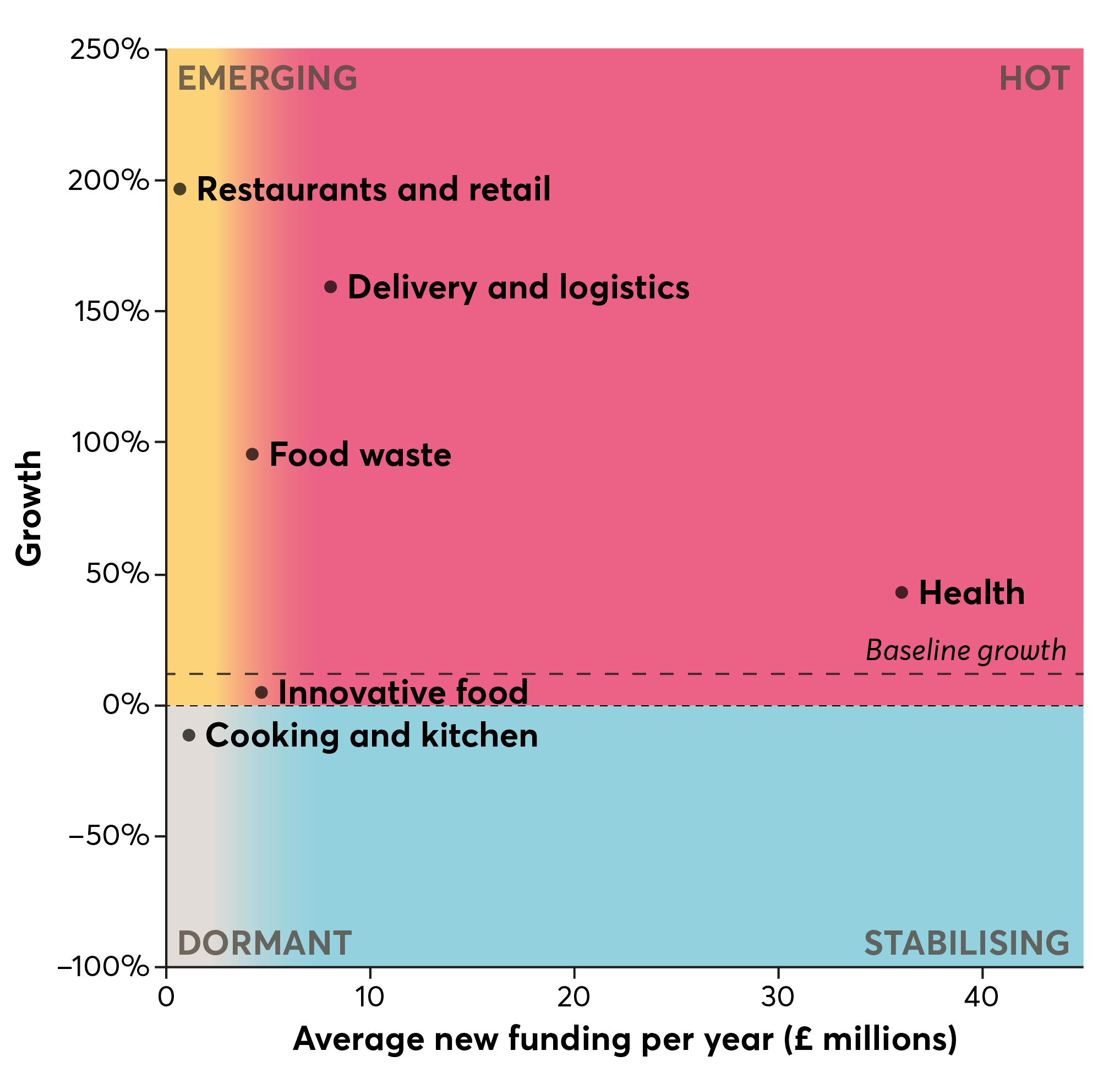

The growth of research projects with potential impact on the wider food environment, however, is not distributed evenly (see Figure 33 below). In terms of research categories we would consider ‘hot’ in our trends typology we find ‘delivery and logistics’ (£8.1 million per year of new funding and 160% growth) and ‘food waste’ (£4.3 million and 95% growth) are the most significant.

This growth is likely rooted in several large-scale funding initiatives, such as the £47 million cross-government multi-year programme on transforming the UK food system announced in 2019. This programme aims to improve the sustainability and health outcomes of the food system.

Average new funding per year and growth between 2017 and 2021

Meanwhile, as shown in the same figure above, funding for projects related to ‘restaurants and retail’ innovations appear to be ‘emerging’, with a relatively small amount of funding (£720,000 per year) but almost 200% growth between 2017 and 2021. Conversely, growth in research funding related to ‘innovative' food’ and ‘cooking and kitchen’ appears to have slowed down, with a rate close to or lower than the baseline funding.

Importantly, outside of the health category, almost half (47%) of the research funding between 2017 and 2021 has been awarded by Innovate UK, which specialises in helping businesses grow through the development and commercialisation of new products, processes, and services. This indicates that a significant proportion of research funding is supporting the commercialisation of innovations that are likely to make an impact in the short term.

Research trends in different innovation categories

Looking at more detailed innovation subcategories reveals further interesting funding dynamics (see Figure 34 below) with, for example, particularly rapid growth for restaurant, food delivery, and alternative protein subcategories. The following sections discuss the trends in each innovation category in greater detail.

A growing body of health-related research

Research projects in the ‘health’ category span a wide range of topics. For example, researchers are studying proteins involved in fat-production in humans, investigating impacts of specific products like seaweed on gut microbiome, and conducting clinical trials to improve bariatric surgery outcomes. Others are developing interventions to shift consumer food choices towards healthy and sustainable diets and reduce time spent sitting while working from home.

In terms of subcategories, we find that funding for ‘diet’ projects, which are focused on (non-personalised) diets and weight management have grown at the fastest pace (60% growth), followed by ‘biomedical’ (35% growth), and a smaller subcategory of ‘dietary supplements’ (6% growth).

Interestingly, we find that funding for research projects specifically mentioning ‘personalised nutrition’ appear to have decreased by about a third in the past five years, which contrasts the positive global trend observed in venture funding data (see Chapter 2). That said, UK-based researchers are pioneering large-scale nutritional studies and it may be the case that our analysis is underestimating the growth in this area, as projects categorised as related primarily to general research on diets and weight management could also generate results relevant to personalised nutrition applications. Nonetheless, the lack of investment in nutrition research has been noted before, for example, by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

While more research and regulation is said to be needed for personalised nutrition to deliver the hoped-for benefits, the number of nutrition app users in the UK has already increased more than four-fold since 2017 and stood at five million users in 2021. If the popularity of commercial personalised nutrition solutions continues to increase, we expect to see it being accompanied by more research into personalised nutrition, especially as there are indications that personalised advice does motivate people to have a healthier diet and lifestyle.

Research on supply chain and food deliveries

Projects in the ‘delivery and logistics’ category are primarily related to research on food supply chains, including work on specific technologies as well broader systems (see Figure 35 below). For example, the University of Birmingham’s project Zero Emission Cold-Chain is one of many researching efficiency improvements and carbon emission reductions for the cold-chain (refrigeration technologies required to keep food fresh). Private companies are receiving Innovate UK grants to develop digital technologies and data trusts to boost supply chain productivity. Meanwhile, a large £6.1 million project led by University of Reading is considering how food systems can be improved to specifically benefit disadvantaged communities.

An emerging subcategory is research specifically on food deliveries, which shows a 200% growth in funding. The majority of these projects have been started since 2020, and include research into technical challenges such as more sustainable delivery packaging and smart labels that facilitate quality assurance. Other projects in this field consider more systemic innovations such as improving access to fresh, healthy food to food-insecure communities by leveraging group buying schemes, and smarter approaches to takeaway meal distribution claiming to reduce delivery costs by 95%, thus boosting the profitability of takeaway deliveries.

Projects in this category have also engaged with the challenges brought about by the pandemic, for example by developing software solutions that connect small businesses with delivery drivers and customers, as well as investigating the role of delivery drivers during the pandemic.

It is interesting to note that the increase in research activity around food deliveries has occurred after the sustained growth in venture funding (discussed in Chapter 2). Hence, this might be seen as a case where research follows on from private sector developments (in contrast to strong signals in venture funding emerging after publicly funded R&D activity).

Research on food waste reduction and packaging

Projects included in the ‘food waste’ category include innovations related to waste reduction via optimised processes or redistribution of surplus food, as well as improved food packaging (see Figure 36 below). Reducing food waste and increasing product shelf life could lower the cost of fresh produce and reduce the risk associated with food getting spoiled. Increasing the attractiveness of healthy food in this way would likely increase access. Therefore, we see the overall growth in this area of research as an encouraging signal.

For example, some projects explore household food waste (responsible for 6.6 million tonnes or 70% of the total food waste in the UK) and investigate novel technologies like paper-based gas sensors that can detect food degradation, or approaches for influencing householders’ behaviours related to purchasing, meal planning and storage. Other projects seek to minimise food waste in the hospitality industry (which generates about 1.1 million tonnes or 12% of total food waste) or investigate artificial intelligence algorithms to optimise demand forecasting as well as the impact of hospitality managers’ attitudes and behaviours on mitigating food waste.

The research funding for these types of innovations appears to have decreased by about 12% between 2017 and 2021, the average yearly funding being around £1.3 million (‘Waste reduction’ in the figure above). Note that we have aimed to include only research related to food consumed by humans, as opposed to research on reusing food waste streams for other purposes such as animal feed or generating energy.

An area of much more rapid growth is packaging innovations, where funding has increased by almost 250% between 2017 and 2021. This research area is underpinned not only by the goal of increasing product shelf life, but also by efforts to increase sustainability, with examples including projects on reusable plastic packaging, as well as algae-derived or plant-based alternatives to plastic.

Innovative food research driven by alternative proteins

Projects in the ‘innovative food’ category have been awarded around £4.7 million in new funding per year between 2017 and 2021. Within this category, we observed that funding for research into alternative proteins has been growing at a rapid pace of about 175% (£1.7 million in new funding per year). Meanwhile, product reformulation, while receiving about £2.5 million per year, seems to have slowed down with a 33% decrease in funding over the same time period.

The growing interest in alternative protein research reflects an increasing focus on sustainability, and specifically on reducing the large amount of carbon emissions associated with producing meat. Projects in this subcategory are investigating multiple different avenues to producing alternative proteins, with 15 projects on plant-based proteins, 14 projects on lab-grown meat, five projects on fermentation and mycoprotein, and 13 projects on other alternative protein research (for example, insect-based protein) between 2017 and 2021. There has also been significant new funding announced in 2022, with at least £2.8 million awarded to fermentation and mycoprotein research (for example, a project to produce protein from grass using yeast) and £3.8 million to plant-based protein research, such as a project to stimulate an increase in the consumption of UK grown pulses.

The decreasing funding for projects in the ‘reformulation’ category should prompt concern given the potential positive impact that these types of innovations could have at the population level. Levels of research funding for reformulation have been boosted in the past by a 2015 £10 million Innovate UK competition for businesses that featured, for example, a project led by global food producer Cargill to produce low calorie biscuits, and a project on using cellulose to increase fibre content in confectionary, bakery and sauce products.

Since 2016, the level of new funding awarded has not reached a similar level, with the exception of £5.7 million funding in 2019 for training doctoral students on soft matter for formulation and industrial innovation – though the food industry is just one of the application areas of this training, alongside plastics, coatings and personal care products. Other recent funding awards include projects aiming to increase dietary fibre content in bread and beverages, and investigating the impact of alternative low calorie fat on appetite and so-called ‘rebound hunger’. The £15 million Diet and Health Open Innovation Research Club (OIRC) and Innovate UK’s £20 million funding competition, announced in late 2022, might provide a further boost to this field of innovation.

Finally, we also distinguished a separate subcategory of ‘innovative food (other)’. This subcategory includes projects that are focussed on optimising specific novel food brands and products but do not have a link to alternative proteins or a clear potential to develop healthier or lower-calorie food. Examples include the development of novel pre-mix flours to boost domestic and international market penetration, and improving the shelf-life of milk for the hot beverage industry. This type of research appears to have received most support in the early 2010s in the form of Innovate UK grants, while recently funding has been lower, at about £465,000 per year on average.

Taken together, the trends in the preceding five-year time period suggest that, when it comes to innovative food research, sustainability might have been a more important driver guiding funders’ priorities than considerations around producing healthier food. There may, therefore, be a case for adjusting the focus and increasing support for reformulation to make food more affordable and healthier. The new funding for OIRC represents an encouraging step in that direction.

Emerging research on restaurants and retail

The growth of funding for the ‘restaurants and retail’ category (which appeared as ‘emerging’) is driven primarily by an impressive, almost 1000% growth in the ‘restaurants’ subcategory. Recent projects in this area include work led by the University of Liverpool to develop public health policies for the out-of-home food sector to efforts to improve diet and reduce obesity, an online platform allowing restaurants to fund and produce meals for vulnerable communities, and innovations for optimising planning to reduce food waste. Some of this growth is also likely a response to the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic, such as a project investigating the impact of the pandemic on giving tips.

Innovation related to ‘retail’ environments has also seen positive, albeit smaller, growth of 60%, with projects ranging from an investigation of the relationship between advertising and customer choice to new technologies for grocery trolley decontamination, food waste reduction in supermarkets, and delivery services for independent community retailers. Note that we excluded projects that did not explicitly mention terms related to the food sector, and hence the total research activity related to all types of retail will realistically be larger than indicated here.

Funding trends for research on ‘cooking and kitchen’ classed as dormant

Finally, we also identified trends in funding for research projects on cooking and kitchen innovations. These, however, appeared to have generally low levels and low growth of funding, and hence can be classed as a ‘dormant’ research area according to our typology (£1.2 million and a 12% decrease between 2017 and 2021).

Projects in this category include, for example: research on advanced mixing and cooking technologies that can reduce the use of salt and fat; use of ultrasound to improve baking processes; algorithms that suggest healthier recipes to users; and machine learning algorithms to recognise activities taking place in the kitchen. Grants have also been awarded to the UK-based kitchen robot developers Moley Services, which is producing domestic kitchen robots, and to the company Karakuri, for its development of a fryer robot.

We identified only three projects directly linked to dark kitchens: the FEED HUB & SPOKE and virtual restaurant projects, both aiming to support restaurants in adopting the dark kitchen model, and an art project. This likely reflects the relative novelty of the dark kitchen concept, and we expect further growth in research in this area in the near future.

Comparing research trends with signals in venture funding (Chapter 2) it seems the private sector growth is presently stronger in the ‘cooking and kitchen’ category area. Kitchen technologies and process innovation could be key to bringing down the price of novel foods. This was recently demonstrated by a US-based plant-based meat start-up claiming to reduce production costs by 95% through a combination of increased automation, reduced energy consumption, optimised production processes, and reduction in waste. Some of the larger venture capital investments, however, appear linked to start-ups working on robots better suited for the fast food industry such as frying robots or the somewhat unsuccessful pizza robots. There is thus clear potential for targeted public funding to support the research and development of cooking and kitchen technologies capable of producing healthy meals.

Conclusion

Our analysis identifies a significant volume of public funding invested into research on food innovations and technologies, as well as obesity and weight management, over the past five years. The fastest growing funding areas of food innovation were those focussed on restaurants, supply chain and food delivery improvements, novel food packaging and alternative proteins.

The issue of sustainability appears to have been a key driver of funding priorities, which is also reflected by the increasing funding for alternative protein research. Conversely, funds for research into reformulated foods and kitchen technologies appear to have decreased in the past five years, as indicated by negative growth estimates.

Looking ahead, there is an opportunity for public funding to provide a meaningful boost for research into healthy, more affordable or reformulated foods, as well as innovations in cooking and kitchen technologies to create more nutritious meals. Given the scale of existing large corporate R&D budgets, public funding would ideally be directed to areas that can benefit innovation in the sector as a whole. For example, this might include support for “challenger brands” testing the commercial viability of new food technologies and products, or addressing consumer issues and concerns when it comes to the adoption of reformulated foods.

Methodology

We used the research project data reported on the UKRI’s Gateway to Research portal and the NIHR’s Open Data site. These projects might be carried out by public or private organisations, and include both basic and applied research. Importantly, this type of data has the advantage of being an early signal compared to publications or patents, as the project abstracts describe research plans for several years ahead.

In working with this data, we used a tailored set of search terms to identify research related to food innovations and technologies, as well as obesity, diets, and weight management. We did not cover innovations in agritech, which are outside the main scope of our research. The search terms were derived through desk research, and iteratively amended after reviewing intermediate results.

We performed a full manual review of the projects returned by our keyword search and complemented it with additional manual search on the Gateway to Research and NIHR's Open Data databases. Note that, while we aimed to minimise overlaps between different innovation categories, single projects were also occasionally assigned to multiple categories or subcategories where appropriate. We took care to avoid double counting of projects when estimating funding and growth rates for aggregated groupings of projects. The final list of identified projects can be found here and the search terms used in the analysis can be found here.

Note that in our analyses we focus on trends over a five-year time period between 2017 and 2021, to capture the direction of UK research funding during the medium-term and smoothen out year-to-year fluctuations. We report a smoothed estimate of research funding growth that compares the rolling three-year average of investment in 2017 versus 2021. Specifically, we calculated the relative percentage increase in the average value in 2019-2021 versus the average value in 2015-2017.

At the time of writing this report, we did not have complete data coverage for 2022, and hence refrained from including it when reporting trends as it might skew the analysis. Nonetheless, where appropriate we also reference recent funding announcements in the accompanying narrative.

For visual clarity, time series of yearly research funding between 2010 and 2021 are plotted using an interpolation method, which preserves the precise values of the underlying (yearly) data points. The change from 2021 to 2022 (for which data was incomplete) is shown using simple linear interpolation. We note that time series of awarded research funding tend to have a jagged appearance, with peaks and troughs. This is due to funding often being awarded in waves depending on funders’ priority areas and programmes, time-bound funding calls, and competitions in any given year.

Finally, as part of this project, we also trialled the use of the OpenAlex dataset to assess the global research publication trends. Initial results appeared to confirm substantial growth in the past decade across all main areas of food innovation, but as further evaluation is still needed we have decided not to include them at this time. The analysis code for research funding analysis can be found in the project’s GitHub repository.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adeola Otubusen for her help in collecting the NIHR data, trialling the OpenAlex dataset and reviewing the initial keyword search terms.