Consuming history:

Three decades of change in how and what we eat

By Pen Vogler

Rates of obesity in the UK population are double what they were in the 1990s. Over the same time period, we've seen big changes in how food is marketed to us, what food is available to us, how much it costs us and how convenient it is to buy. In this guest article, author and food historian Pen Vogler shares 10 ways in which the food most readily available to us now is so much unhealthier than it was three decades ago.

There’s nothing quite like the contrasting pleasures of salty, crunchy potato crisps and a refreshing drink; it was the taste of the pub and the end of the working day in the 1990s. Snack technology has leapt out of the pub since the days when prawn cocktail was a novelty; bringing us more extruded shapes, fancier flavours and more ingenious ways to deliver high-salt, high-fat treats. As crisps came in bigger packs (in theory, ‘made for sharing’), and got more sophisticated (Kettle chips started in 1988), supermarkets devoted more and more shelf space to them. All those new kinds of Monster Munch, Cheesy Wotsits and Doritos specially designed for kids to afford on the way back from (or to) school; it would be rude not to, wouldn’t it?

‘Once you pop, you can’t stop’ said Pringles in 1996, revealing a new fact: they were being designed for us to eat more.

Drinks are also now designed for us to take in more calories without realising. In the 1990s caff, we ordered tea or coffee and added the sugar ourselves. The coffee shop chains that spread along our high streets around the turn of the century (1), have developed creamier and sweeter drinks; gingerbread lattes, iced coffee, bubble tea, mocha, chai latte, a salted caramel frostino. These drinks might pack 12 or 13 teaspoons of sugar but because we don’t put it in ourselves; it is nearly invisible. The bitterness of caffeine masks the sweetness of sugar; tea, coffee and cola all smuggle a bigger sugar hit past our taste buds and condition us to want more. Manufacturers answer this craving by making not just drinks, but biscuits, cakes, snack bars, breakfast cereals, even burger buns and hotdog rolls, sweeter and more, well, moreish.

We have to crunch and sip between meals to fit in all these extra snacks. Or use them as a cheap replacement for a hot meal. The trouble is that high sugar snacks lead to mood and energy slumps but there is always a shop or a vending machine nearby with another instant, brightly packaged cheap fix.

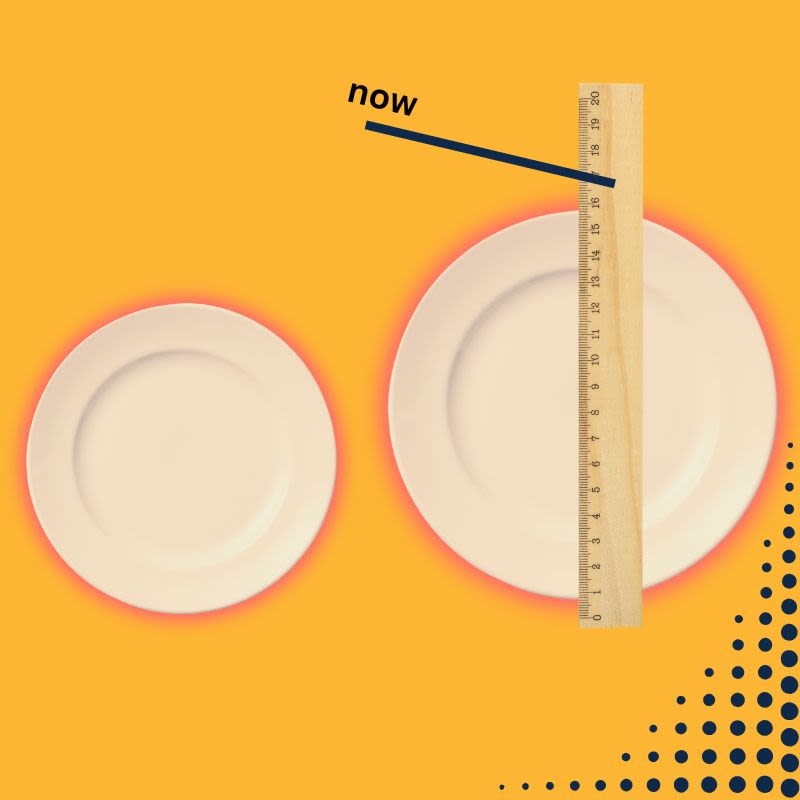

In the queue at the 1990s sandwich bar or bakery, you thought about what you were going to have – coronation chicken, egg mayonnaise, cheese and tomato… before somebody behind the counter made it for you. Lots of bakeries doubled up as sandwich bars, so you could stock up on bread too. After M&S introduced the first boxed sandwich in 1980, sandwich bars and bakeries began to disappear. Supermarket sandwiches were cheaper, but they made up profits by selling more food; the ‘meal deal’ added a high-sugar (or sweetener) soft drink and a snack – crisps or confectionery. Confusingly, the drink and snack might be labelled as ‘2 portions’ though the calories are given for ‘1 portion’.

Grocery shops introduced self-service when they discovered by accident in the 1950s and 1960s that interaction with a shopkeeper acts as a brake; without it we buy more than we need, which leads to more waste and bigger waists. Self-service, marketing, bogofs (buy one get one free), ‘three for twos’, portion sizes and other social ‘nudges’ have made us eat more over the years. We buy way more bread than we can eat and throw away about 25 million slices a day.

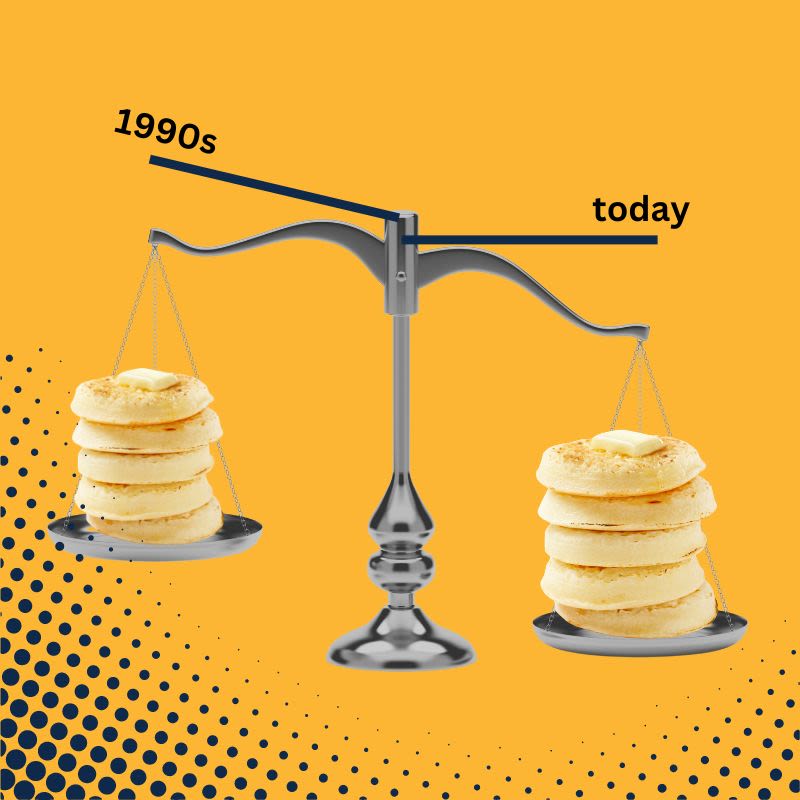

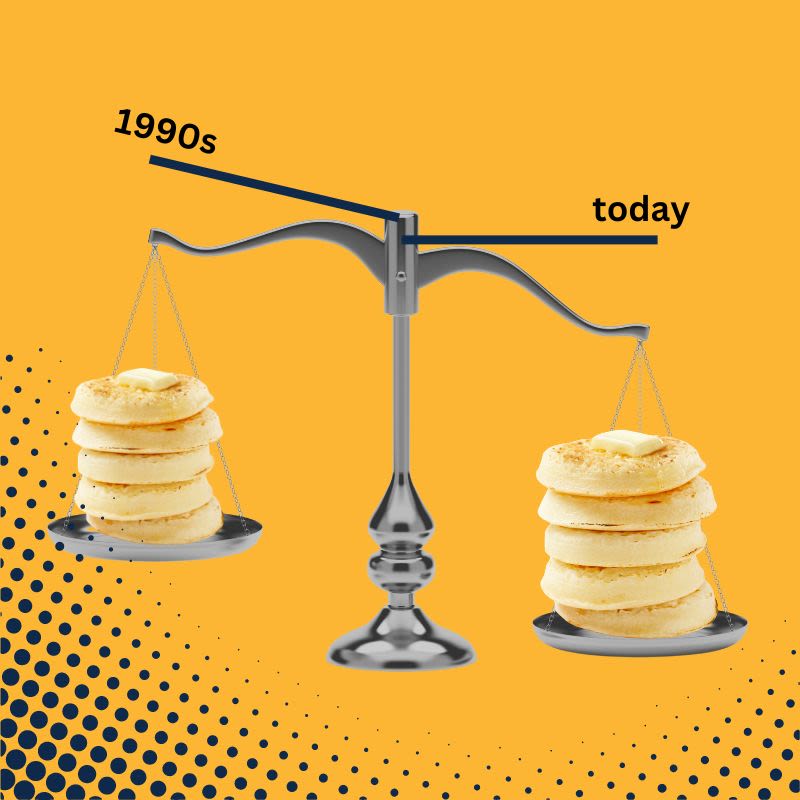

We’re beginning to get a handle on this; many supermarkets have a voluntary ban on bogofs, for example, and we throw away less food than we did 20 years ago. However, we also eat more because food has gotten bigger. A crumpet, for example, bulked up from 40g in the early 1990s to 55g today and a supermarket shepherd’s pie ready meal nearly doubled from 210g to 400g. The opposite – smaller portions for the same price – known as shrinkflation, is very unpopular and gathers much more media coverage than an increase in portion sizes.

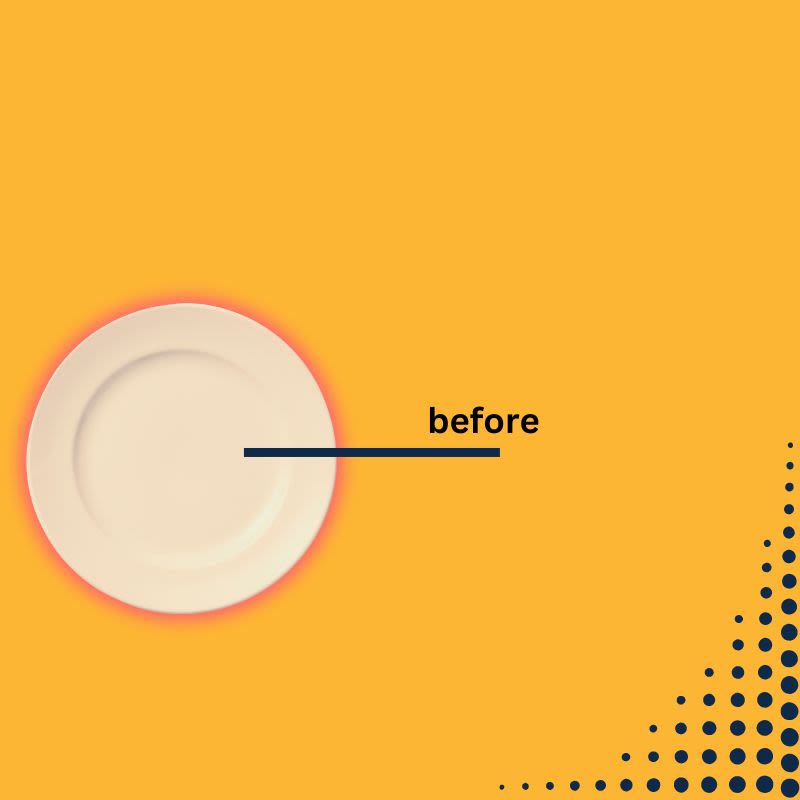

Even our plates encourage bigger portions. Your grandparents’ dinner plates were 3-4cm smaller than modern ones, and their wine glasses were around two-thirds of the size. Could some crockery shrinkflation help us with our portion control?

[Nesta’s recent analysis shows that sandwiches and meal deals are top contributors to the calories consumed from food purchased or eaten outside of homes.]

Ask anyone about the food adverts they remember from the end of the last century and the same ones are bound to pop up. The Smash aliens, the Hovis boy (directed by Ridley Scott in 1973), perhaps Gary Lineker as the cheeky face of Walkers Crisps (which began in the mid-1990s). Early advertising was quite generic; mums, dads and kids might all see it together. In the 1990s, though, people started to worry about how much advertising on TV and cartoons on cereal packets and sweets were targeted directly at children. ‘Pester power’ was born.

As the internet became part of everyday lives, marketing agencies soon figured out that they could advertise directly to youngsters on websites and devices.

It was particularly effective with younger kids who didn’t realise the games, jingles, puzzles, quizzes, cartoons and film and TV partnerships were, in fact, adverts. The stroke of marketing genius was that their parents wouldn’t see it. The smartphone multiplied those opportunities. Like hungry lions, singling out the young or weak zebra from the herd, adverts target the individual – child or adult – at their most vulnerable points. Hungry? Unpopular? Low in energy? There’s nothing an ice cream, a chocolate bar or a burger can’t fix. A whole generation has grown up to understand food as something we choose to please ourselves and consume alone.

The smartphone-free childhood movement is currently focused on children’s mental health. Should we be talking about its role in dietary health too?

There is a joke that an angler’s idea of hell is to catch a fish every few minutes because it gives them no reward for their skill and patience. Something similar has happened to the treat of eating out.

If Brits were eating delicious, home-cooked meals in the 1990s, they weren’t sharing them with tourists and visitors; and Britain had a reputation for ghastly restaurant fare. Eating out affordably meant Italian, Indian or Chinese; posh meant French. Fish and chips were a treat for Fridays – payday. Takeaway meant just that; you went, ordered, paid, waited and took it away… it was a novelty when you could shave 15 minutes off the palaver by phoning your order through in advance and when Domino’s Pizza started online orders in 1999… that was radical.

Some think the journey to appetising British food started with the first gastropub, The Eagle, in Clerkenwell in London in 1991. Wagamama and Nando’s both opened in 1992. Restaurant chefs and cooks – we know who they are – began to reach celebrity status with TV series. Hot meals from cultures all over the world – Thai, Greek, Persian, Mexican, Japanese – brought deliciousness and variety to the high street. British restaurant culture is now among the best in the world and dining in – and out – has transformed our lives. It’s also become more casual and accessible, for those who can afford it. In London, in the two decades before the pandemic, there were quite a few more restaurants, but the number of cafes and takeaways has more than doubled.

In many high streets, the only hot food available is stuff that used to be an occasional treat; fried chicken, burgers, pizza and chips.

The pandemic pumped up our use of takeaways even further and it’s stayed high ever since; nearly half of our calories are eaten at home but come from fast food, takeaways or delivery-only ‘dark kitchens’ (and this is might be an underestimate). But here's the rub. Businesses making hot food for us are thinking of their bottom line, not the size of our bottoms. Their meals are saltier, sweeter, fattier and around 21% more calorific than a dish we’d cook for ourselves.

Those apps though, might also have some upsides. There are fresh-food options; veg boxes, milk rounds and meal delivery kits for easy cooking at home. These are healthier, more rewarding and can even be cheaper than a ready meal.

In the 1990s, if you wanted a healthier diet you’d go to a ‘whole’ or ‘health’ food shop. The words were broadly interchangeable until dieticians and the food industry began to argue that only some parts of the whole food were healthy. ‘Low-fat’ became the mantra. Yogurts, biscuits, cakes and meal replacements drinks were all reformulated by removing fat and replacing it with stabilisers and, for taste, sugar. The realisation that this sugary, low-fat food wasn’t helping us win the war on weight helped launch a new arsenal of diets - keto, Atkins, paleo, Dukan – where carbs replaced fat as the enemy. Carbs are a broad category and some cheap, nutritious foods such as wholegrains, oatmeal and rice found themselves in the sin bin with the white stuff in a packet.

With fat and carbs both under suspicion, protein has emerged as the favoured macronutrient. There’s intense marketing of products that barely existed in the 1990s such as protein bars, protein shakes and whey powder. The trouble is that many of these ‘health foods’ lack the fibre, vitamins and minerals of whole food and often have additional salts, sugars and sweeteners.

So much for ‘macronutrients’. At least we all agree that micronutrients – vitamins and minerals – are essential and that’s why we increasingly see claims such as ‘added Vitamins C’ or ‘rich in zinc’ on a packet. Our bodies, however, need a broader range of micronutrients. We got more of them in the 1990s from basic groceries such as milk, meat, fish, brown bread and green veg.

Overall, vitamins and minerals in our diets have decreased since the 1990s.

Over the last 30 years, ideas of ‘healthy’ food have changed at a dizzying rate and dietary advice and marketing have added to our confusion. The only healthy outcomes from ‘health food’ have been the profits of the industry that makes it. But three-fifths of us are trying to eat more healthily; edible seeds and rice cakes are in the consumer shopping basket (a measure of inflation) for the first time. There’s a commercial opportunity, too, for returning to ‘whole food’.

In parts of Britain, the evening meal is called ‘tea’ because the magic of a cup of tea was that it transformed a cheap, cold meal - usually bread and cheese - into a hot one. Since the 1970s, the UK has witnessed that magic transformation of wheat-to-hot meal in… the Pot Noodle. Post-war Japan invented instant noodles as an alternative to bread; a more culturally familiar way of using the American wheat shipped in to prevent starvation.

Noodles are cheap, storable and fuel-efficient; in the pandemic years we ate 11% more.

People love them for their comforting texture (thanks to wheat and palm oil) and zingy taste (thanks to flavour enhancers and lots of sodium). But that sodium is pushing up incidences of heart disease, high blood pressure and stroke, which makes health professionals very anxious.

Instant noodles have been cleverly marketed to young men, in particular, who feel they are too busy to cook. Students without kitchens in their halls of residence, site workers, budget travellers and people (often kids and teenagers) with limited cooking skills are all targets for the 137 different types of instant noodle available (the second highest in the world after China).

There was a steep rise in the number of people living – and eating – alone in the 1990s; but snowballing housing costs mean people born after 1980, are more likely to be sharing with friends or living with parents, and falling out over the washing up or sharing the oven. Kitchens are smaller too; over the last 50 years the average size of a kitchen in a newbuild has been squeezed by over 2 metres square or, to put it another way, the size of a kitchen table. The diminutive air-fryer is a healthy solution for some households.

The health crisis is tangled up with the housing crisis but tiny changes – such as healthier noodles – will help. Britain’s sodium targets are slowly having an impact… which is good for everyone’s blood pressure.

In the 1990s, it was common for butchers, fishmongers, greengrocers and bakers, who get up very early to buy fresh food from wholesale markets or to bake to close at 4pm. It wasn’t even legal for shops to open on a Sunday until 1994. Women, who are more likely to take on much of the cooking, now work more hours than in the 1990s. So it’s not surprising that more of us turned to convenience shops and supermarkets and, for car drivers, out-of-town hypermarkets and service stations to buy our food.

But how did this affect what we eat?

To profit from extended hours, shopkeepers must ensure their core stock lasts. In the past this meant food in tins and the freezer, however, increasingly, foods like cereals, biscuits, chocolates, crisps, snack bars and even bread have been reformulated to have a long shelf-life. Artificial preservatives as well as traditional ones such as sugar and salt keep food for longer and make it tastier. Manufacturing in huge quantities makes it very cheap. We increasingly turned to shops that could give us time-saving ready meals; in the early 1990s two-thirds of us had a microwave; now nearly everyone does. Meanwhile, on the high street, competition from hairdressers, nailbars and fast-food takeaways, drives up business rates.

Shops selling fresh food, having to charge more, have disappeared from many poorer areas.

However, one time-waster has been welcomed back into our time-pressed lives; the bakery queue! Instagram and TikTok have boosted the number of people willing to wait for painstakingly made bread and beautiful cakes.

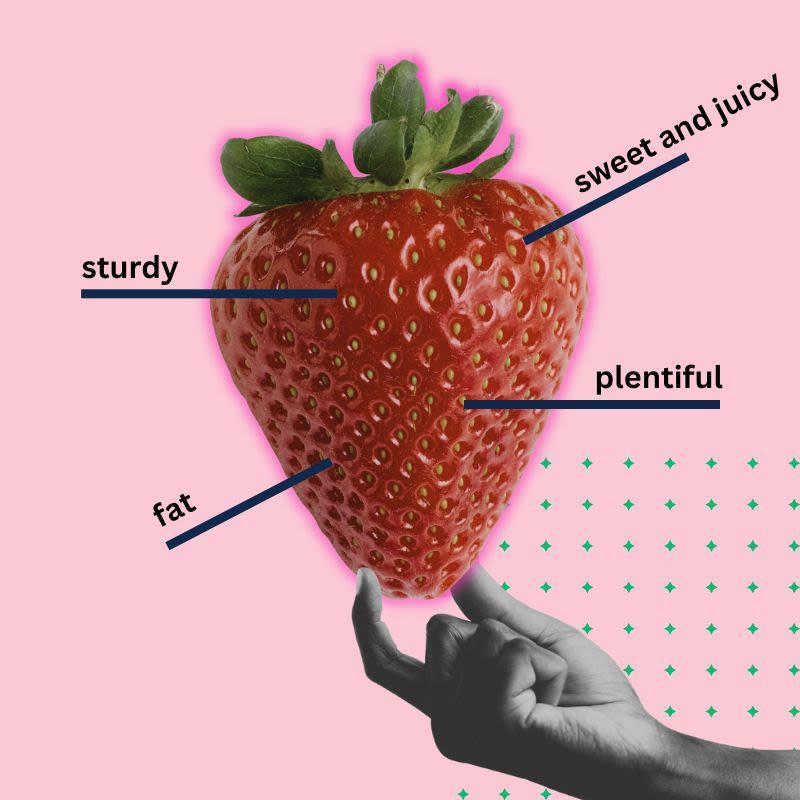

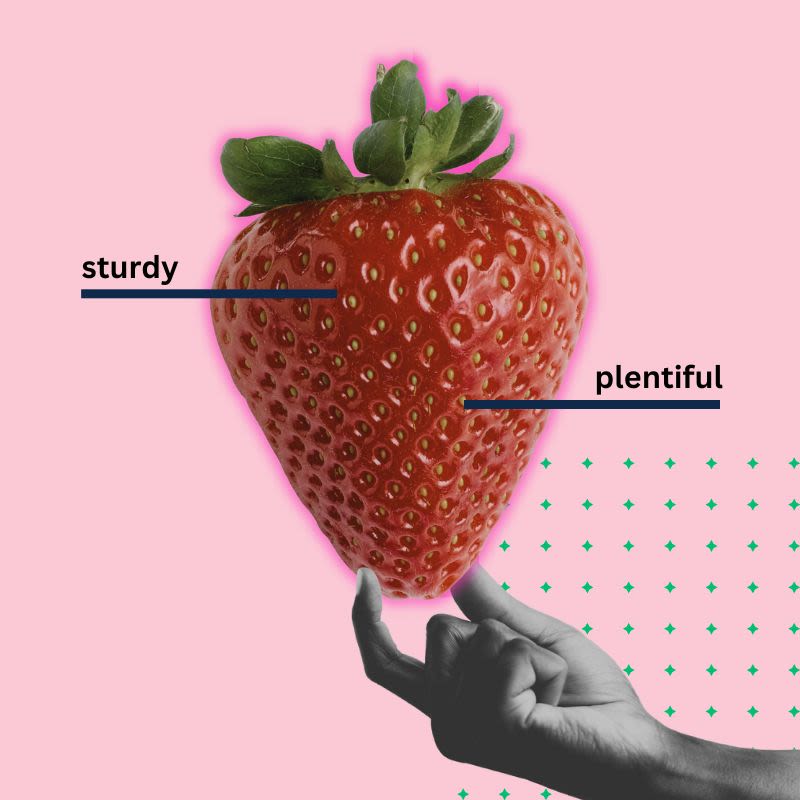

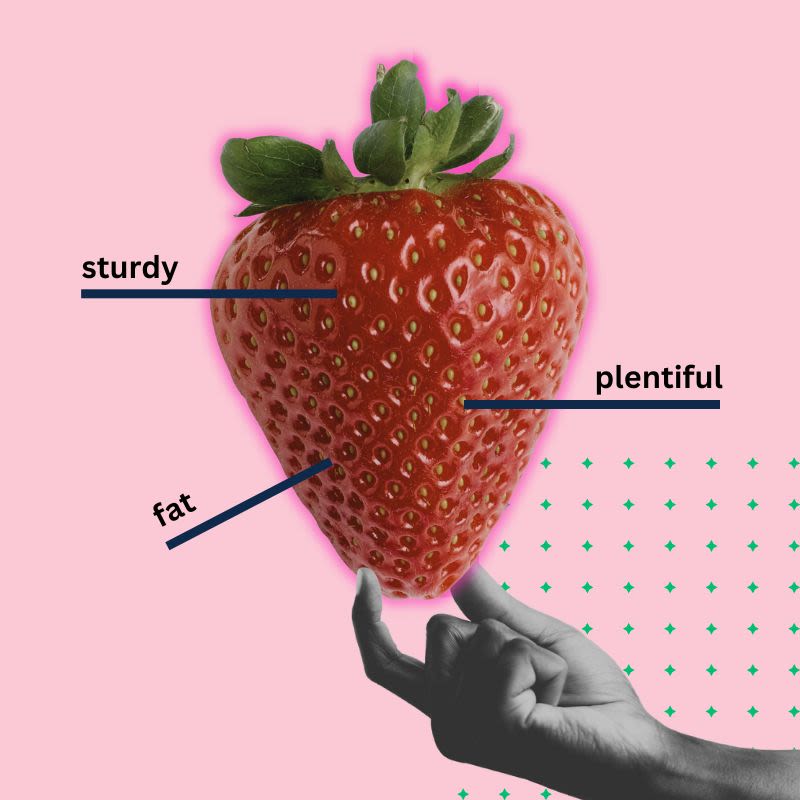

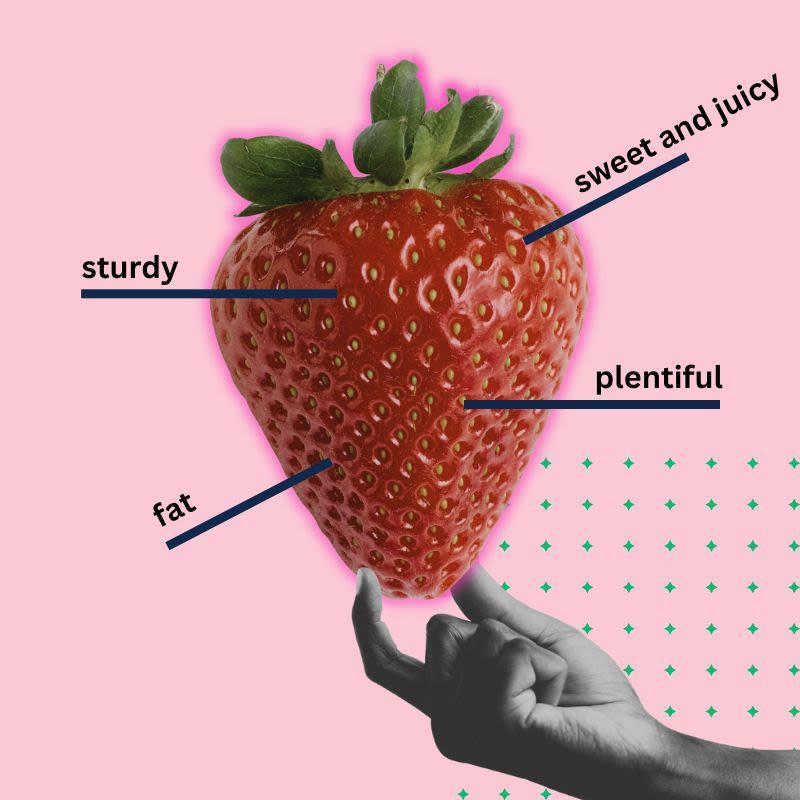

During the summer, many supermarkets sell more strawberries than any other food, even basics such as bread, milk and potatoes. In fact, while we buy less bread (especially brown bread), milk and fresh potatoes, we eat over three times more soft fruit than we did in the 1990s.

In the 1980s and 1990s, nobody rated the fruit and veg in Britain’s supermarkets, especially not women, who were their major customers. Supermarkets had to up their game. They jetted berries in from Southern Europe and North Africa but many were too watery or sour. British berries were world class but strongly seasonal which is why they have been the perfect Wimbledon treat since Victorian times. Every variety had its own merits; disease-resistant or heavy-cropping or sweet and juicy or long-fruiting. For many years, the grocery market was dominated by the ‘big four’ supermarket chains: Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons, which meant that they could pressure strawberry growers to produce a near-magic berry; plentiful, fat, sweet, juicy and sturdy enough to be transported.

British strawberries are a major success story. The season begins in early spring and continues through to the autumn, thanks to skillful agronomists, polytunnels and greenhouses. The magic of berries is that they are an instant treat, whereas traditional locally-grown veg such as fresh potatoes, cauliflowers, sprouts, peas and beans are more time-consuming to prepare and less loved.

Happily, since the 1990s, chefs have started championing veg and we’re learning from other international cuisines and vegetarian cooks to enjoy it roasted, stir-fried, curried and in instant, crunchy, fresh salads.

Back when Bradford introduced the first LEA-funded school dinners, the Domestic Subjects head, Marian Cuff, created menus that were nutritious, balanced and cheap. But she knew that it wasn’t just the food that was important; children sat around a table, with a cloth and some flowers in the middle, and used cutlery and crockery. Perhaps the most important thing she gave them was time, patience and attention. For decades this was the school meal ideal (even if the reality sometimes fell short). Although the quality of school meals declined in the 1980s (thanks to changes in funding and legislation), people in the 1990s had grown up understanding that school lunches were a shared occasion that deserved a bit of time and care. There were workers’ canteens in most workplaces in the 1990s (82% in 1995 compared with 47% in 2015) (2) and workers took an hour for lunch. Eating together can be fraught; Dad’s weird way of cooking, picky children, bolshy teenagers, argumentative relos… But many people still feel that it is important and enjoyable; psychologists show that it boosts hormones such as oxytocin that are good for our health and happiness.

The time we spend eating meals together has fallen dramatically over the decades. Life feels busier; finding time to eat together is a balancing act with commuting, part-time jobs, after-school clubs, social lives. Shift workers in particular find it harder to fit in regular mealtimes. Technology has made eating solo so easy: the ready-meal, the ping of the microwave and on-demand TV. Although time spent preparing and sharing meals has fallen over the decades, there is happier news that parents, relatives and carers now spend more time with children and less on cooking (and cleaning).

Can we keep that important time with kids and prepare a meal? Cooking with kids is time-consuming, floury, messy, chaotic… and lots of fun.

When KFC first rolled out its branches in Preston, its first customers, used to fish and chips, quickly learnt to change their ways. They couldn’t have chips, they were told, but ‘fries’ and they definitely couldn’t have vinegar on them. Fast food – particularly American fast-food chains – are keen to have a consistent and standardised menu all over the world (although they make small changes to adapt to local cultures and religions) which can be eaten without cutlery or plates. Whereas ethnic restaurateurs such as Indian and Chinese adapt to local tastes wherever they go, American brands act like the stroppiest of elite chefs; the local customer must simply be a consumer who plays no part in the creation of the food. The power of marketing and cultural images from US TV and film promoting standardised junk food flattens regional variations – even something as minor as vinegar on chips. It is often said that Britain doesn’t have a national cuisine beyond fish and chips and roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. In fact, it has plenty of cheap, nutritious, regional dishes: oatmeal pancakes, pease pudding, Scotch broth, Welsh caul, Lancashire hotpot, Cullen Skink, Haggis, neaps and tatties. These dishes are clinging to the margins… but not disappearing.

Local dishes might not have multi-billion-pound advertising budgets, but local food does have support from small organisations who know that community connection to farmers, growers and cooks, is a route to a healthier, tastier life, and not as niche or old-fashioned as perhaps we once thought.

A CONCLUSION

From the swirl of changes in our environments over the last three decades, three patterns emerge. In the first place, businesses use change as opportunities to sell more food; part of the way they do this is by adding more calories from salt, sugar and fat, so we enjoy it more. Secondly, we have been moulded to be enthusiastic but passive consumers; our active participation has been whittled back to a minimum. Lastly, the retail environment has minimised our exchanges with other people – shopkeepers, sandwich-makers, family members – who act as brakes on overconsumption. The less we – and other people – are involved with the food we eat, the more likely it is to be unhealthy.

A CONCLUSION

From the swirl of changes in our environments over the last three decades, three patterns emerge. In the first place, businesses use change as opportunities to sell more food; part of the way they do this is by adding more calories from salt, sugar and fat, so we enjoy it more. Secondly, we have been moulded to be enthusiastic but passive consumers; our active participation has been whittled back to a minimum. Lastly, the retail environment has minimised our exchanges with other people – shopkeepers, sandwich-makers, family members – who act as brakes on overconsumption. The less we – and other people – are involved with the food we eat, the more likely it is to be unhealthy.

End notes

The great snack takeover

(1) Costa Coffee began in the 1980s and had 41 stores in 1995 (when it was bought by Whitbread), Café Nero opened in London in 1997; Starbucks came to the UK in 1998.

We still have time for each other – just not at mealtimes

(2) Reduction in meal times in ‘Unequal Eating’ in What We Really Do All Day, Gershuny and Sullivan, Pelican, 2019

How international is squeezing out local

There were 400 Macdonalds in the UK in 1991 and 1433 branches in 2024

https://www.mcdonalds.com/gb/en-gb/newsroom/history.html

https://www.scrapehero.com/location-reports/McDonald's-UK/#:~:text=How%20many%20McDonald's%20restaurants%20are,McDonald's%20restaurants%20in%20the%20UK.

In 2023 there were an estimated 4424 fried chicken shops across the UK

https://www.ft.com/content/1c973989-c44f-4062-88c4-53e7fba0baaa