Back to the future: why has it become so hard to eat healthily?

Back to the future: why has it become so hard to eat healthily?

The food that surrounds us has become less healthy over time

Obesity is one of the major drivers of ill health in the population, leading to conditions like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers. If we want a healthy society, we need to make it easier to eat healthily.

High levels of obesity are a relatively recent issue in our history. In 1993, obesity rates were 15% in England, whereas by 2022 they were 29% – almost doubling in just under 30 years. So what is happening? It can't just be a collective failure of willpower. We’ve managed to smoke and drink less during the same time period. What's changed in the last 30 years? That's where the food environment comes in.

What is the food environment?

The food environment is how food is promoted, advertised and displayed, how much it costs us and how convenient it is to buy. Our food environment profoundly affects what we eat and, consequently, our health. It's easy to think our food choices are entirely personal, but our eating habits are constantly shaped by our surroundings. Availability and convenience drive many decisions: when healthy options are scarce or require effort, we naturally choose what's accessible. This isn't just about where we live – it encompasses everything from the shops we pass and strategically placed snacks at checkouts, to targeted social media content and appetising photos on delivery apps on our phones. Even our social circles influence what feels normal to eat.

We're also working against some basic human wiring. Our brains still crave energy-dense foods – useful when food was scarce for our ancestors, but less helpful in today’s world where we’re surrounded by abundant, calorific options designed to be irresistible.

So, what can we learn from looking at how our food environment has changed in the last 30 years?

The food that surrounds us has become less healthy over time

Obesity is one of the major drivers of ill health in the population, leading to conditions like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers. If we want a healthy society, we need to make it easier to eat healthily.

High levels of obesity are a relatively recent issue in our history. In 1993, obesity rates were 15% in England, whereas by 2022 they were 29% – almost doubling in just under 30 years. So what is happening? It can't just be a collective failure of willpower. We’ve managed to smoke and drink less during the same time period. What's changed in the last 30 years? That's where the food environment comes in.

What is the food environment?

The food environment is how food is promoted, advertised and displayed, how much it costs us and how convenient it is to buy. Our food environment profoundly affects what we eat and, consequently, our health. It's easy to think our food choices are entirely personal, but our eating habits are constantly shaped by our surroundings. Availability and convenience drive many decisions: when healthy options are scarce or require effort, we naturally choose what's accessible. This isn't just about where we live – it encompasses everything from the shops we pass and strategically placed snacks at checkouts, to targeted social media content and appetising photos on delivery apps on our phones. Even our social circles influence what feels normal to eat.

We're also working against some basic human wiring. Our brains still crave energy-dense foods – useful when food was scarce for our ancestors, but less helpful in today’s world where we’re surrounded by abundant, calorific options designed to be irresistible.

So, what can we learn from looking at how our food environment has changed in the last 30 years?

The shifting retail landscape

We’re buying more and more food as time goes on. Between 1985 and 2015, real-term consumer spending on food in the UK (excluding restaurants) grew by 38%. By 2022, total sales of food retail were £171 billion, and are forecast to grow 25% by 2028.

Part of the reason we are buying more is that where and how we buy food has undergone a significant transformation. While large supermarkets remain dominant, the rise of online retail and the proliferation of smaller convenience stores have altered how we buy food and what we end up eating.

The online food shopping market has experienced strong growth over time, with the UK market reaching £23.6 billion in 2024. Home delivery services of just the top three retailers (Asda, Tesco and Sainsburys) now cover 98% of GB households. This digital shift means ordering food is now easier than ever, and has increased opportunities for targeted marketing that can influence what we consume.

Another significant change is the rise of convenience stores on our streets, from corner shops to small convenience branches of supermarkets. 65% of people in the UK have a convenience store less than a quarter of a mile from their home, and the average customer visits a convenience store between two and three times a week. The total value of sales for 2024 from convenience stores is £49.4 billion, and the convenience sector is expected to grow a further 12% by 2029. This matters because many of these stores rely on sales of less healthy products.

A study looking at 13 convenience stores across the UK found that 89% of products displayed at checkouts were unhealthy. Every time we pop into a shop to buy something, we must navigate a sea of brightly packaged, tempting treats that are often high in sugar, fat, salt and calories. Research shows that placing products in key locations, such as entrances, aisle-ends and checkouts, increases sales by as much as a factor of five.

Retailers are also spending more than ever on price cuts – £2.6 billion, up nearly 9% from last year. These promotions are widespread and highly effective at influencing what people buy and eat. In particular, multi-buy deals and meal deals – often featuring foods high in fat, sugar, and salt – have become a regular part of the retail landscape, making less healthy options more visible and appealing to shoppers. If we’re on the fence about whether to buy chocolate or not, a prominent price promotion is often enough to sway us.

The shifting retail landscape

We’re buying more and more food as time goes on. Between 1985 and 2015, real-term consumer spending on food in the UK (excluding restaurants) grew by 38%. By 2022, total sales of food retail were £171 billion, and are forecast to grow 25% by 2028.

Part of the reason we are buying more is that where and how we buy food has undergone a significant transformation. While large supermarkets remain dominant, the rise of online retail and the proliferation of smaller convenience stores have altered how we buy food and what we end up eating.

The online food shopping market has experienced strong growth over time, with the UK market reaching £23.6 billion in 2024. Home delivery services of just the top three retailers (Asda, Tesco and Sainsburys) now cover 98% of GB households. This digital shift means ordering food is now easier than ever, and has increased opportunities for targeted marketing that can influence what we consume.

Another significant change is the rise of convenience stores on our streets, from corner shops to small convenience branches of supermarkets. 65% of people in the UK have a convenience store less than a quarter of a mile from their home, and the average customer visits a convenience store between two and three times a week. The total value of sales for 2024 from convenience stores is £49.4 billion, and the convenience sector is expected to grow a further 12% by 2029. This matters because many of these stores rely on sales of less healthy products.

A study looking at 13 convenience stores across the UK found that 89% of products displayed at checkouts were unhealthy. Every time we pop into a shop to buy something, we must navigate a sea of brightly packaged, tempting treats that are often high in sugar, fat, salt and calories. Research shows that placing products in key locations, such as entrances, aisle-ends and checkouts, increases sales by as much as a factor of five.

Retailers are also spending more than ever on price cuts – £2.6 billion, up nearly 9% from last year. These promotions are widespread and highly effective at influencing what people buy and eat. In particular, multi-buy deals and meal deals – often featuring foods high in fat, sugar, and salt – have become a regular part of the retail landscape, making less healthy options more visible and appealing to shoppers. If we’re on the fence about whether to buy chocolate or not, a prominent price promotion is often enough to sway us.

The digital dining boom

Remember eating out in the 1990s? It actually felt like an event. Craving McDonald's meant making the trek to one of just 400 UK locations. Ordering takeaway involved hunting down a crumpled menu and having a live conversation with someone on the phone. Fast forward to today, and McDonald's’ UK footprint has tripled to 1,450 branches.

But that's nothing compared to the digital revolution. The UK's online food delivery market has skyrocketed from £14 billion in 2019 to £35 billion in 2024. By 2021, a quarter of all fast food calories were being ordered online.

This isn't just a pandemic blip either. While takeaway consumption jumped by 50% in the pandemic, a study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows that it has stayed elevated, with food purchased away from home jumping up 10.6% from 2022 to 2023 alone. The result? Six in ten Britons now order a takeaway at least once a week.

Restaurant and takeaway food is 30% more energy-dense than home-cooked meals, and people who eat a takeaway once a week consume an extra 75 -104 calories daily compared to occasional diners. What once required genuine effort now happens with a few thumb swipes.

We've essentially removed all the friction from ordering and eating food from outside our homes. The convenience is undeniable, but it's quietly reshaping how we eat in ways we're only beginning to understand.

The digital dining boom

Remember eating out in the 1990s? It actually felt like an event. Craving McDonald's meant making the trek to one of just 400 UK locations. Ordering takeaway involved hunting down a crumpled menu and having a live conversation with someone on the phone. Fast forward to today, and McDonald's’ UK footprint has tripled to 1,450 branches.

But that's nothing compared to the digital revolution. The UK's online food delivery market has skyrocketed from £14 billion in 2019 to £35 billion in 2024. By 2021, a quarter of all fast food calories were being ordered online.

This isn't just a pandemic blip either. While takeaway consumption jumped by 50% in the pandemic, a study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows that it has stayed elevated, with food purchased away from home jumping up 10.6% from 2022 to 2023 alone. The result? Six in ten Britons now order a takeaway at least once a week.

Restaurant and takeaway food is 30% more energy-dense than home-cooked meals, and people who eat a takeaway once a week consume an extra 75 -104 calories daily compared to occasional diners. What once required genuine effort now happens with a few thumb swipes.

We've essentially removed all the friction from ordering and eating food from outside our homes. The convenience is undeniable, but it's quietly reshaping how we eat in ways we're only beginning to understand.

The rise of snacking and ready meals

Snacking has undergone significant changes since the 1990s. While snacking is a natural part of our diet, our options have become more calorie-dense and sugar-packed.

Between 1992 and 2017, the sugar content in snacks per 100g grew by 23%, and chocolate bar consumption rose 13% over the same period. Walk down a supermarket aisle and you'll see a plethora of choices that didn't exist in the 1990s – Walkers alone has released over 140 flavours since their original 1948 crisp, with constant innovations accompanied by big marketing campaigns and celebrity endorsements.

We're also relying heavily on ready meals. Purchases have doubled since 1992, with pizza sales jumping 143%. A 2025 UK poll shows that nearly half of us eat ready meals weekly. But convenience comes with trade-offs; over half (56%) of ready meals are high in salt, 42% are high in saturated fat, and 71% are low in fibre. The rise of dual-income households has slashed time for cooking, making convenient solutions like ready meals and takeaways often a necessity rather than optional.

This combination of calorie-packed snacks, heavy marketing, and nutritionally poor convenience foods replacing home cooking has contributed to a modern food environment that drives much of today's obesity challenge.

The rise of snacking and ready meals

Snacking has undergone significant changes since the 1990s. While snacking is a natural part of our diet, our options have become more calorie-dense and sugar-packed.

Between 1992 and 2017, the sugar content in snacks per 100g grew by 23%, and chocolate bar consumption rose 13% over the same period. Walk down a supermarket aisle and you'll see a plethora of choices that didn't exist in the 1990s – Walkers alone has released over 140 flavours since their original 1948 crisp, with constant innovations accompanied by big marketing campaigns and celebrity endorsements.

We're also relying heavily on ready meals. Purchases have doubled since 1992, with pizza sales jumping 143%. A 2025 UK poll shows that nearly half of us eat ready meals weekly. But convenience comes with trade-offs; over half (56%) of ready meals are high in salt, 42% are high in saturated fat, and 71% are low in fibre. The rise of dual-income households has slashed time for cooking, making convenient solutions like ready meals and takeaways often a necessity rather than optional.

This combination of calorie-packed snacks, heavy marketing, and nutritionally poor convenience foods replacing home cooking has contributed to a modern food environment that drives much of today's obesity challenge.

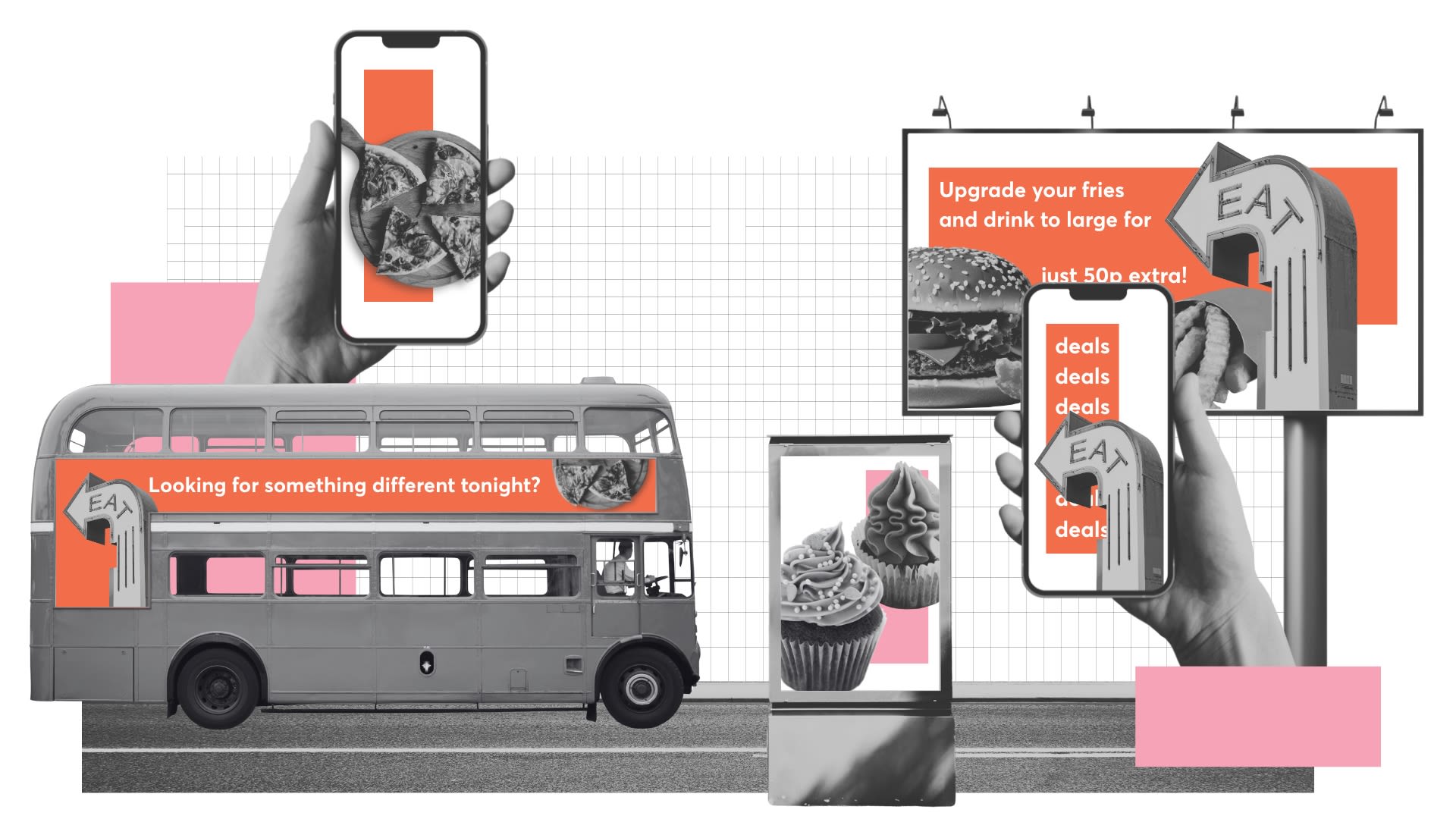

The advertising avalanche

It's not just our eating habits that have changed – the way we consume media has too. In the 1990s, you might have seen a few food ads on TV, on billboards or in a magazine you might read once a week. Nowadays, we're met with a constant barrage of advertising: pings to our phone, pop-ups on social media, offers to our inbox. Companies can now use a huge range of data to build a picture of their potential customers and target digital advertising directly to the customers that are most likely to buy their products.

Between 2007 and 2017, online advertising spend on food and drink increased by 450%. 78% of all advertising spend is now online, ensuring we're constantly exposed to targeted food marketing during our average of 4+ hours of daily screen time. 59% of online food and drink adverts are for HFSS (high in fat, salt or sugar) products. When we stream TV shows and films, we see adverts for global food brands and delivery apps that make us wonder if ordering in at half time might be easier than cooking dinner. And that's all before we've stepped outside.

Once outside, we’re met with more advertising, with bus stops showing burgers and billboards suggesting we grab a pastry with our coffee – all part of the £400 million spent on street advertising by food companies in 2024 alone.

The scale of advertising nowadays is staggering: approximately a third (32%) of food and soft drink advertising spend goes towards less healthy foods. A survey of 1500 adults found that 85% saw high fat, sugar and salt products advertised every week, with people from less affluent areas 50% more likely to be exposed. Most concerning, when researchers studied outdoor advertising, they found junk food ads were six times more likely to appear in deprived areas than wealthy ones, meaning people in these communities must work much harder to resist the constant pull toward unhealthy food and drink.

The advertising avalanche

It's not just our eating habits that have changed – the way we consume media has too. In the 1990s, you might have seen a few food ads on TV, on billboards or in a magazine you might read once a week. Nowadays, we're met with a constant barrage of advertising: pings to our phone, pop-ups on social media, offers to our inbox. Companies can now use a huge range of data to build a picture of their potential customers and target digital advertising directly to the customers that are most likely to buy their products.

Between 2007 and 2017, online advertising spend on food and drink increased by 450%. 78% of all advertising spend is now online, ensuring we're constantly exposed to targeted food marketing during our average of 4+ hours of daily screen time. 59% of online food and drink adverts are for HFSS (high in fat, salt or sugar) products. When we stream TV shows and films, we see adverts for global food brands and delivery apps that make us wonder if ordering in at half time might be easier than cooking dinner. And that's all before we've stepped outside.

Once outside, we’re met with more advertising, with bus stops showing burgers and billboards suggesting we grab a pastry with our coffee – all part of the £400 million spent on street advertising by food companies in 2024 alone.

The scale of advertising nowadays is staggering: approximately a third (32%) of food and soft drink advertising spend goes towards less healthy foods. A survey of 1500 adults found that 85% saw high fat, sugar and salt products advertised every week, with people from less affluent areas 50% more likely to be exposed. Most concerning, when researchers studied outdoor advertising, they found junk food ads were six times more likely to appear in deprived areas than wealthy ones, meaning people in these communities must work much harder to resist the constant pull toward unhealthy food and drink.

So what is the solution?

Sometimes, to move forward, we need to look back. In just 30 years – within many of our lifetimes – , our food environment and diets have slowly worsened. But it is possible to reverse this trend. Just as small changes over time have made our health worse, small changes to the food we see and buy, that are sustained over time, are what’s needed to make it easier to eat more healthily. How small, you might ask? On average, reducing average daily calories by just 216 kcal for people living with excess weight – equivalent to a Kit Kat Chunky – would halve obesity. Our blueprint toolkit for policymakers shows which solutions exist to reduce obesity without breaking the bank.

A powerful example is the UK government’s newly announced healthy food standard. Through targets for supermarkets, it encourages subtle but impactful shifts, such as product reformulation, better shelf placement of healthier options, and clearer promotion of nutritious foods.

Reshaping our food environment in a way that works for the modern world is essential. But if we all – government, businesses, the NHS and individuals – play our part, we can improve our food environment so that it works for us, not against us.